Marina Silva: Insistence That May Yet Pay Off

Brazil may not yet be ready for her, but Marina Silva is the name to watch. The former senator for Acre, a small state in the western part of the Amazonian rainforest, and presidential candidate for the Socialist Party, Marina Silva was tipped as the likely successor to President Dilma Rousseff before her campaign tanked just days before the polls opened for the first of two electoral round on October 5. Marina Silva ended in third place with barely 21% of the vote – a good show, but not quite good enough.

Brazil may not yet be ready for her, but Marina Silva is the name to watch. The former senator for Acre, a small state in the western part of the Amazonian rainforest, and presidential candidate for the Socialist Party, Marina Silva was tipped as the likely successor to President Dilma Rousseff before her campaign tanked just days before the polls opened for the first of two electoral round on October 5. Marina Silva ended in third place with barely 21% of the vote – a good show, but not quite good enough.

Perhaps it was too much to ask. Marina Silva is black, from a modest background, evangelical, incorruptible, and an environmental activist to boot. She survived five bouts of malaria while growing up on a rubber tree plantation and battled hepatitis and metal poisoning as well. Taken in by nuns after both her parents passed away, she became the first of her family to learn how to read and write. Marina Silva was sixteen when she passed her literacy exam.

Working her way through college as a housemaid, she obtained a degree in history from the Federal State University of Acre in 1984. By now politically active, she helped form the state’s first labour union. Ten years later, Acre voters sent Marina Silva to the federal senate in Brasília. Here, Brazil’s youngest-ever senator fought tirelessly for social justice and sustainable development – concepts at the time mostly seen as quixotic and detrimental to private business interests.

“The dichotomy between development and the environment is one I cannot accept. The two are part of the same equation.”

Elected on the ticket of the Workers’ Party, Marina Silva was invited to join the first cabinet of President Luiz Inácio da Silva – aka Lula – in 2003 as minister for environmental affairs. From that lofty perch, she proceeded to insist on plausible environmental impact studies for any major project undertaken in the country.

Not only did Marina Silva draw the ire of big business, she also frequently upset fellow ministers bent on short-tracking large development projects such as the upgrading of the 4,476 kilometre-long BR163 highway – linking the more developed southern states with the Amazon Region – and the proposed diversion of the waters of the São Francisco River to irrigate farmland in four drought-stricken states of North-eastern Brazil.

In 2008, Marina Silva resigned from the cabinet after a rather public row with Lula’s chief of staff: The same Dilma Rousseff who went on to become president and last October claimed a second term in office. At the time, Dilma Rousseff accused her colleague of wilfully blocking economic growth by denying development projects construction permits.

“The dichotomy between development and the environment is one I cannot accept. The two are part of the same equation. It is not possible to further economic development without taking biodiversity and environmental conservation into account,” said Mrs Silva just days after returning to her seat in the senate.

A while later, she left the governing Workers Party and joined the Greens to become their candidate for the presidency. In the 2010 election, Marina Silva won 19% of the popular vote in a performance that surprised nearly all pundits. Though ending in third place and eliminated from the decisive second round of voting, she had become a force to be reckoned with in Brazilian politics.

In 2014, Marina Silva again tried for the presidency, growing her support another two percentage points and winning in major urban centres such as Brasília, Rio de Janeiro, and Vítoria.

The reason she’s the one to watch is simple: Brazilian voters admire candidates who keep on defying the odds to prove conventional political wisdom wrong. It took two crushing defeats (in 1994 and 1998) before voters in 2002 allowed Lula into the Palácio do Planalto – the futuristic presidential palace in Brasília.

Marina Silva – consistent in her message, upright, and self-made – possesses many qualities that are both admirable and absent in most of her peers. As the need for a shift towards sustainable development policies becomes clearer as time progresses, Marina Silva can very well hitch a ride on the changing times. Worn-out economic models are, yet again, failing Brazil as it seeks to rediscover the path to economic growth. If she manages to stay on message, Marina Silva may yet make it all the way to the top.

You may have an interest in also reading…

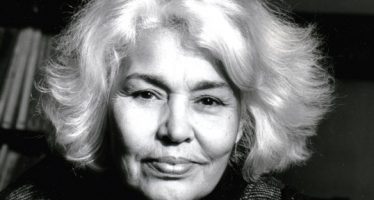

Dr. Nawal El Saadawi – An Honourable Life

Like so many of our other heroes, Dr Saadawi has seen the inside of a prison cell because of her

Acharya Balkrishna: Billionaire Monk Makes Modesty and Empathy Watchwords for Progress

Acharya Balkrishna projects an aura of modesty, often clad in a traditional India dhoti, the simple garment of the people

Otaviano Canuto, World Bank Group: Macroeconomics and Stagnation – Keynesian-Schumpeterian Wars

Policy makers in the advanced economies at the core of the global financial crisis can make the claim that they