The Summer Before Dark 2.0

Paris is under a curfew and Madrid under a state of emergency. In the Benelux, bars and cafés have been closed whilst elsewhere in Europe governments are almost uniformly moving towards a quasi-lockdown. The second wave was perhaps slow to gather speed but is now steamrollering the continent with a ferocity that surpasses even the darkest predictions. In some countries, both the infection rate and the number of people diagnosed with covid-19 are significantly higher than those recorded in April and May at the peak of the pandemic’s first wave. The muted 2020 holiday season increasingly looks like the summer before dark.

Paris is under a curfew and Madrid under a state of emergency. In the Benelux, bars and cafés have been closed whilst elsewhere in Europe governments are almost uniformly moving towards a quasi-lockdown. The second wave was perhaps slow to gather speed but is now steamrollering the continent with a ferocity that surpasses even the darkest predictions. In some countries, both the infection rate and the number of people diagnosed with covid-19 are significantly higher than those recorded in April and May at the peak of the pandemic’s first wave. The muted 2020 holiday season increasingly looks like the summer before dark.

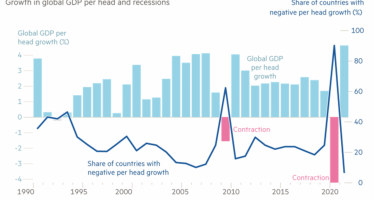

The economy has seesawed in tandem with the novel virus. Analysts expect Q3 numbers to show record GDP growth across the EU after a sharp Q2 contraction. However, the last quarter of the year – the one that was supposed to consolidate post-pandemic gains and pull up the results for the full year to near zero – is likely to deliver a coup de grace and set the stage for a steep recession. All chatter about its form – V-, L-, U-, or W-shaped – has vanished as the I-shape comes into view – a precipitous drop off the figurative cliff with no branches to hang on to and little in the way of a cushion at the bottom.

The double-dip recession is already in the bag and a triple-dip has become a distinct possibility. A perusal of today’s headlines confirms the dire straits. The Guardian reports on street protests against toughened rules turning violent in Prague and Dublin. The paper also cites a snapshot study of the retail sector that tabulated over 6,000 (net) store closures in the UK between January and June – a record number.

The Frankfurter Allgemeine concludes that the pandemic rages out of control in Berlin-Neukölln where increasing numbers of infected people refuse to self-quarantine. Germany’s paper of record also reports that European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde has suggested the creation of a permanent EU recovery and development fund underwritten by eurozone member states. The ECB forecast of fourth-quarter growth in excess of 3 percent has wisely been binned. The bank’s belief that the eurozone would return to its pre-pandemic size by 2022 was ditched as well.

The Italian Corriere della Sera carries news about a project to fast-track the assembly of a number of ICU-trains that can be mobilised to alleviate the pressure on overwhelmed local and regional hospitals. The first such train compositions, each equipped with 130 ICU beds, will roll out of the Angel Group’s workshops in about two months’ time.

Second Coming

In the UK, the pandemic’s second coming roughly coincides with the impending end of the Brexit transition period which kept the country inside the EU single market in all but name. The transition was to pave the way for a comprehensive free trade agreement, but negotiations have stalled over fishing rights and the need for a level playing field and a strengthened conflict adjudication mechanism. On Saturday, Prime Minister Boris Johnson seemed to suggest an end to the talks and informally notified EU chief negotiator Michel Barnier not to bother coming to London. Brussels ignored the advice and Johnson refrained from instructing his negotiating team to break off conversations. However, with both sides entrenched in their positions, it seems highly unlikely that an agreement – or fig leaf – will emerge.

Meanwhile, the ECB’s increasingly frantic attempts to stoke inflation came to naught with the eurozone consumer price index dipping to minus 0.3 percent in September – a four-year low coming on the heels of August’s minus 0.2 percent. Core inflation, a measure which strips out the most volatile prices of food and energy, amongst others, descended to just (plus) 0.2%.

After injecting trillions into moribund eurozone economies and slashing interest rates deep into negative territory, the ECB is now ready to double down on its policy by expanding the €1.35 trillion bond-buying programme with a supplemental €500 billion. A growing number of analysts take issue with the policy which has merely shifted inflation from consumer prices to asset classes such as real estate and stocks.

Disconnect

The enormous disconnect between the struggling ‘real’ economy and the buoyant one featuring on the big boards of major stock exchanges is starting to embarrass and scare investors who fear that their day of reckoning may be drawing near. A few major investment banks have already cautioned clients against believing the present bull run may still have legs.

In her report to the European Parliament, Lagarde last week said that inflation is expected to remain negative over the coming months. She also optimistically forecasted a 1.3 percent rise of the consumer price index by 2022. ECB Vice-President Luis de Guindos ascribed the disappointing results to ‘ephemeral effects’ and predicted that next year’s bounce back will see a return to inflation.

Though the European Union has agreed to a €750 billion recovery fund, the first payouts are not expected for another year. However, this week the commission is expected to begin raising €100 billion on international capital markets for the awkwardly named SURE (support to mitigate unemployment risks in an emergency) package agreed by the council in May.

Market watchers expect the bond sale to provide an early indication of Brussels’ sovereign risk premium. The EU boasts a AAA/stable outlook rating from the three major credit rating agencies. The commission has currently some €50 billion in outstanding bonds but is expected to raise an additional €200 billion next year. Though EU bonds are trading at a higher yield than the benchmark 10-year German bund, the dearth of AAA-bonds available has investors excited. It is likely that the EU will be able to place its bonds at a negative yield.

Draft budgets submitted by eurozone member states to the European Commission show the aggregate fiscal deficit ballooning to almost €1 trillion – or 8.9 percent of GDP – next year. This represents a 10-fold increase over 2019 when the major markets of the eurozone showed a healthy surplus. The gap between revenues and spending is expected to widen to well over 10 percent of GDP in Spain, Italy, Belgium, and France. The Netherlands, Germany, and Ireland dwell at the other end of the scale but still overspend by massive amounts equal to around 6 percent of their national income.

The current fiscal splurge exceeds the one that followed the banking crisis of 2010 when eurozone member states overspending averaged out at 6.6 percent. However, this time around fiscal largesse comes with the blessings of the International Monetary Fund and other former guardians of fiscal rectitude. Globally, the Corona pandemic has prompted governments to up their spending and/or cut taxes by an estimated $11.7 trillion, equivalent to 12 percent of global GDP.

You may have an interest in also reading…

Click OK and Call Me in the Morning — How Online has Changed Shopping for Meds

Social media have been on about the New Normal since the start of the pandemic. People are still looking forward

Otaviano Canuto: Shapes of the Post-Coronavirus Economic Recovery

Data recently released on the first-quarter global domestic product (GDP) performance of major economies have showed how significant the impact

The Twilight Zone of Fiscal Stimulus

Now in its second iteration, the corona pandemic no longer inspires the blind fear it did just six months ago.