Argentina Looks Good, Brazil Not So Much

Brazil: Rio de Janeiro

Argentina has defaulted on its public debt – again. The country is familiar with the script that follows and unlikely to be intimidated by upset creditors. In fact, Argentina is seen blazing a trail for other countries grappling with debt loads that have suddenly become unsustainable after the corona pandemic unhinged economies, disrupted cross border trade, and ushered in a yet-to-be-defined new normal.

President Alberto Ángel Fernández, barely seven months in office, has received considerable praise for his government’s decisive response to the pandemic. He managed to unite the nation by clearly indicating that its needs trump those of bondholders.

Late May, both Fitch and S&P downgraded three tranches of the country’s sovereign bonds to ‘D’ after a $500 million payment was missed and negotiations on the partial restructuring of the public debt all but collapsed.

Pushed over the edge for the ninth time since its founding in 1816, Argentina’s default script is well rehearsed and contains few surprises. Downtown Buenos Aires was duly plastered with posters featuring the silhouette of a vulture and demanding a break with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and an immediate end to ‘debt bondage’. Though the placards change, the message stays the same. It is also a slightly inappropriate message as the fund has turned into Argentina’s prime cheerleader.

The prospect of a debt default no longer causes anxiety or fear. Few countries are more experienced in dealing with economic shocks than Argentina. In 2001, the country staged the world’s largest sovereign debt default when it suspended payment on the $132 billion owed to foreign banks and investors. Since then, and notwithstanding its poor record, Argentina’s debt stock has ballooned to a staggering $414 billion, equal to 93 percent of GDP, proving that it takes two to tango.

Over the past decade, private investors looking for yield have showered Argentina with funds. In 2017, not even a year after the country ended a long court battle with a group of private equity funds refusing to accept a settlement on the 2002 default, Argentina managed to issue a $2.75 billion 100-year bond, carrying a juicy 7.9 percent coupon. Eager buyers placed orders worth almost $10 billion, raising some eyebrows amongst analysts mindful of the country’s rather poor credit record. They had a point: the 100-year bond now trades for 37 cents on the dollar.

Argentina’s present troubles stem, to a considerable degree, from its government’s prudent approach to the corona pandemic. Entering a strictly enforced lockdown early on, the country managed to limit the spread of the novel virus and avoid a major outbreak. Whilst the approach yielded better than expected results, it also paralysed an already shaky economy that had been put on IMF life support in September 2018. In a surprise move, at the time interpreted as a motion of confidence, the fund arranged credit facilities worth $57.1 billion for Argentina – the largest bailout package in IMF history.

The government of President Fernández now says it needs to refinance at least $65 billion of short-term debt to put the economy on a more sustainable footing. Some major investors seem to agree. BlackRock and a few other large bondholders have indicated that they recognise the need for debt restructuring given the extraordinary circumstances.

Nobel laureates Joseph Stiglitz and Edmund Phelps have joined a group of prestigious economists calling for a ‘constructive approach’ to Argentina’s troubles. They argue that the Argentine government acted responsibly by shielding its citizens from both the virus and the economic consequences of the pandemic. French economist Thomas Piketty pointed out that private investors were ‘fully aware’ of the risks when they bought into high-yield Argentine bonds.

Argentina has proposed to reduce coupon payouts, introduce a three-year grace period, and push maturities back by up to a decade. However, three major groups of creditors rejected the plan outright. Whilst recognising that a consensus may prove hard to reach, Economy Minister Martín Guzmán remains hopeful that an agreement can yet be negotiated. Talks are ongoing but a considerable gap remains with the government demanding a $500 million reduction in annual debt servicing costs.

Should an agreement prove elusive, Argentina’s major corporations may be locked out of the global capital market and forced into default as well. Guzmán fears that the damage may already have been done and said that post-corona credit will be scarce with bondholders reluctant to engage unless the government comes up with a major fiscal and administrative reform package. However, the post-corona new normal points in the opposite direction. Argentina is no exception to the global trend that sees states assume a more proactive role in the management of the economy.

Still, Argentina seems well-poised to recover relatively quickly. In the 2000s and whilst shut out of capital markets, the country staged a remarkable economic recovery under its own power. It may well do so again. This lesson from recent history is not entirely lost on its creditors either and helps Guzmán navigate the brink.

Though slightly less indebted and with a much more robust domestic industrial base, Brazil is likely to discover that a lack of national unity and political resolve may undermine attempts to kickstart the sluggish economy. The shenanigans of President Jair Bolsonaro do not inspire confidence. Although the president has consistently prioritised the economy and refused to order a national lockdown, the country’s GDP is expected to shrink by almost 13 percent in the second quarter. Analysts predict Brazil will register a 6 percent economic contraction over the full year, putting a premature end to the tentative return to growth initiated in 2017.

Facing the sharpest economic recession in its history, Brazil seems singularly ill-equipped to meet the challenge. The pandemic fractured the political landscape and further deteriorated the relationship between the federal government and the powerful states. Governors have stepped up as the president squandered his authority and standing by consistently downplaying the pandemic and displaying an almost heartless indifference to the suffering of Brazilians.

After he assumed control of the country in January 2019, Bolsonaro promised to implement a vast programme of structural fiscal reform that was to transform Brazil into a global economic powerhouse and an engine of growth. However, the quest to Make Brazil Great got off to a slow start as the divided federal congress declined to fast track approval of key measures and the economy responded only hesitantly to the dawning of the new era.

The pandemic has now derailed the Bolsonaro Administration’s entire agenda. With political strife nearing an all-time high, congress is unlikely to support any of the president’s initiatives, postponing, yet again, the promised renaissance of an overregulated economy marred by pervasive corruption, social inequality, and capricious rule.

Foreign investors cast a wary eye on the rising tensions between the president and his widely respected and powerful economy minister who is considered a lone voice of reason in the cabinet. Minister Paulo Guedes has grown frustrated with the president’s repeated interventions and apparent disregard for fiscal prudency. Though both agree that the Brazilian economy faces collapse unless the state-ordered lockdowns end, Guedes emphasises the need to immediately bring down the fiscal deficit which is expected to reach 8.7 percent of GDP by year’s end. Guedes also resists attempts to bridge the spending gap with freshly minted money, fearing a return of inflation.

In a curious turn of events, Brazil now finds itself on the periphery of global events as the country becomes the focal point of the corona pandemic whilst the Bolsonaro Administration loses control of the crisis and is unable to forge a degree of national unity or a coherent response to the emergency. Meanwhile, Argentina, long the enfant terrible of the continent, is displaying a level of maturity that holds promise. As a result of getting his priorities straight, Fernández enjoys the backing of the IMF even as he stopped some debt payments. Whatever shape the new normal takes, good governance will likely carry the post corona recovery.

You may have an interest in also reading…

The Final Destiny of the Trillions

When the going gets though, the weak are moved aside. A depressingly large number of the 181 US corporations that

Otaviano Canuto: More Than One Coronavirus Curve to Manage – Infection, Recession and External Finance

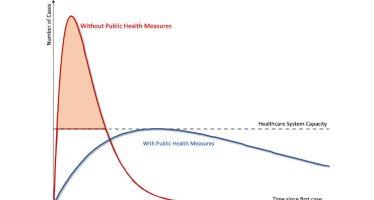

Flattening Coronavirus Curves – Otaviano Canuto First appeared at the Policy Center for the New South The global reach of

Islamic Development Bank Deploys Sukuk to Counter Corona Impact

Respond, Restore, and Restart. That is how the Islamic Development Bank Group (IsDB) aims to tackle the economic fallout of