Brazil’s Economic Crossroads: Which Path Will It Choose?

Rio De Janeiro, Brazil: Aerial panorama of Christ and Sugar Loaf Mountain

Latin America’s largest economy entered the pandemic before it could heal from its worst recession in decades.

First appeared at Americas Quarterly

As the pandemic unfolds, Brazil is paying a huge human cost, with the number of victims rising quickly. The scar of COVID-19 will take a long time to heal. And the country will also have to battle on the economic side, where the impact will be deep and long-lasting.

Starting from a jump in the already high level of debt in relation to its GDP, coming from both sides of the equation: spending has skyrocketed while a steep decline in its gross domestic product is expected for this year. The trajectory for the country’s economy over the next decade, it is clear, will be lower than what was expected prior to COVID-19.

Current projections illustrate Brazil’s coming fiscal crossroads: The country can choose either stagnation and insolvency or a gradual fiscal adjustment with better growth prospects. And whether any growth will even be sustainable will depend on Brazil’s ability to move forward with structural reforms that can lift private investments. Regaining the country’s attractiveness for foreign investments will play a key role in its recovery.

For that to happen, though, the agenda of structural reforms – tax, business environment, sector regulatory framework – must return to the forefront, once the current focus on recession-flattening policies can be left behind. Structural reforms that aim at boosting private investments will improve the debt-to-GDP ratio. The multi-year horizon typical of infrastructure investment decisions, i.e. going beyond the current short-term dire economic prospects, means the participation of the private sector in them is necessary to circumvent the lack of fiscal space that will be the reality for Brazil in the decade ahead.

Higher investment in infrastructure and other long-term projects would bring improvements on both demand and productivity sides. The sooner the regulatory framework for private sector investments in sanitation — where changes were recently approved in Brazil’s congress — roads, etc. is fine-tuned, the faster investment decisions will be made.

No time to waste

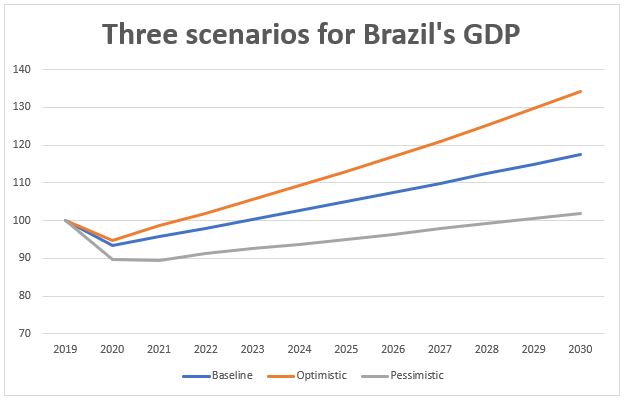

The latest forecasts by the Senate’s Independent Fiscal Institute (IFI in its Portuguese acronym) project Brazil’s GDP will fall by 6.5% this year, and only partially recover ground next year with a 2.5% growth rate. Depending on the length of the still-unfolding pandemic and its impact on the economy, as well as on the effectiveness of the policies so far implemented to flatten the recession curve, we could also anticipate both an optimistic and a pessimistic path: In the best-case scenario, a contraction of 5.3% in 2020 would be followed by 4.3% growth in 2021. In the worst-case scenario, GDP would shrink by 10.2% this year and by 0.3% the next.

The IFI report projects the potential annual GDP growth rate at 2.3% in the period from 2022 to 2030, with basic real interest rates assumed to converge to 3.3% per year. Such figures are lifted or downgraded in the two other scenarios, the more optimistic and the pessimistic one depending on how favorably — or unfavorably — the country-risk premium will affect exchange rates, inflation, and real interest rates.

The co-evolution of the country-risk premium and the public debt-to-GDP ratio will be key to defining whether Brazil’s GDP takes the more optimistic or more pessimistic trajectory. Like in most countries, anti-catastrophe public policies taken to flatten the recession curve, together with a fall in tax revenues, will – temporarily but steeply – raise the public sector nominal deficit and significantly lift the level of public debt as a proportion of GDP. As a result, even assuming a return to the pre-COVID-19 fiscal framework – including the constitutionally-mandated federal government spending cap that was suspended to allow for the emergency measures – the country will face a fiscal adjustment challenge steeper than the one already prevailing before the pandemic.

Turning the tide on outflow

It is worth paying attention to the link between structural reforms and private investments, as well as to the changes — in magnitude and profile — of foreign capital flows to Brazil in the recent past. Although a positive current-account balance is expected in 2020, the tendency is one of deficits. Capital inflows have more than covered those deficits in the recent past and, in fact, as recently highlighted in reports by A.C. Pastore & Associates, they are to be held responsible for the dramatic accumulation of foreign reserves by the country, since the mid-2000s, which has underlined its solid position in external accounts. Besides their implications for exchange rates and domestic financial conditions, such capital inflows were a positive factor for investments in the Brazilian economy.

After Brazil lost its investment grade, the country’s capital account changed directions, and outflows were accentuated during the pandemic. Since the 2015-16 recession, the flow of foreign money to equities and fixed-income instruments has turned negative while the transition to lower domestic interest rates has also diminished the country’s attractiveness as a yield provider. The partial return of capital into financial instruments in the last few weeks must not be confounded with a return to previous conditions, as they have reflected a partial unwinding of the portfolio adjustments that happened with the global financial shock in March. Foreign direct investments, in turn, are not likely to fill the void soon in the absence of new opportunities.

Therefore, a combination of a credible return to the fiscal adjustment path and investment-friendly structural reforms would also have the additional positive effect of making possible new rounds of foreign capital inflows. That would reinforce the likelihood that the Brazilian economy will go down the optimistic path of growth and debt, rather than the pessimistic one.

About the Author

Canuto is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and principal of the Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank.

You may have an interest in also reading…

Nicholas Brady: Soccer Finance and the Pragmatist Who Fixed a Debt Crisis

Back in the days when a top-scoring soccer player could be enticed for a few million, Brazilian attacker Romario set

London Stock Exchange (LSE) Facing Competition from NYSE Euronext

London Stock Exchange (LSE) is facing stiff competition from NYSE Euronext, which have already captured its first client to switch

UNIDO: Nowadays it’s Tough on Tigers

Poorer developing countries may find it much harder under current conditions to foster industrial development and structural change than earlier