Agustín Carstens: Central Banker of Central Banks

Agustín Carstens General Manager, BIS (Bank of International Settlements)

In an unexpected volte-face, BIS (Bank of International Settlements) general manager Agustín Carstens agreed that cryptocurrencies do not, after all, pose a risk to the global financial system.

Carstens is finally paying attention to a phenomenon he previously discarded as a “combination of a bubble, Ponzi scheme, and environmental disaster”. When the BIS general manager takes note, mainstream cannot be that far away.

In a new report on the rise and impact of virtual money, Carstens notes that the value of cryptocurrencies is determined, to a large extent, by national legislation. Emerging frameworks that seek to regulate Bitcoin and other alternative currencies are anchored for the most part on the point where virtual money interacts with the real thing: banks. Sooner or later, cryptocurrencies must be exchanged for actual money and when this happens, regulators can step in.

Carstens agrees that the situation is likely to change when cryptocurrencies grow out of their niche and move mainstream, lessening the need to interact with actual money. However, that moment is still far away. However, the BIS general manager does caution against ignoring the cryptocurrency scene and advises regulators to keep close tabs on developments: “It is important to remain vigilant, monitor developments, and respond to potential threats.”

According to BIS research, cryptocurrencies are sensitive to regulatory decisions that ban or restrict initial coin offerings (ICOs) or regulate the legal status of assets denominated in alternative currencies.

This works both ways: cryptocurrencies receive a boost wherever regulators display a willingness to accommodate them. In this regard, the cryptocurrency community is anxiously awaiting a ruling from the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) whether to allow Bitcoin exchange traded funds (ETFs) to be launched. The decision may come as early as next year.

Carstens notes that the crypto market remains fragmented, and offers plenty of room for arbitrage as significant price differences occur across jurisdictions, reflecting their attitudes – and degree of hostility – towards alternatives to fiat money.

General manager of the BIS since September 2017, Carstens arrived at the institution from the Central Bank of Mexico which he headed for seven years. His appointment to the “central bank of central banks” was, at the time, widely considered a consolation prize for having lost out to Christine Lagarde in the race for the directorship of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Carstens served for slightly over three years as the IMF’s deputy managing director.

Established in 1930 and headquartered in Basel, the Bank of International Settlements is owned by 60 central banks – jointly representing almost 95% of global GDP – and charged with facilitating international co-operation between central banks. A fringe institution until the early 1970s, and at various times slated for dissolution, BIS reinvented itself after the collapse of the Bretton Woods monetary order which resulted in the reappearance of floating exchange rates and the need for an institution to help maintain financial stability.

During the most recent annual Jackson Hole get-together of central bankers, Carstens did issue a warning against trade wars, saying their potential to disrupt a finely tuned global system is consistently underestimated. He spoke about the brewing of a perfect storm, set off by a rise in protectionist measures and fuelled by their negative consequences. Causing fireworks at a usually tranquil, if not boring, event, Carstens did not mince his words when he remarked that the trade barriers erected by the US administration – and answered in kind by both the EU and China – are likely to push up consumer prices. This, in turn, would force the US Federal Reserve to step-up its interest rate hikes, which “would widen the interest premium to the rest of the world”, and could push the dollar higher.

The BIS general manager concluded that current policy presents a double whammy to US exporters, which would face not only new trade barriers but also a deteriorated exchange rate.

Emerging markets, Carstens argues, are at risk from increased market volatility, as a higher dollar and restrictive monetary policies drain the pool of funds available for their development, and cause higher financial outflows as yield may be more easily be obtained in mature markets.

You may have an interest in also reading…

Mukhisa Kituyi: Growing Intra-African Trade Flows

What Africa sells to Africa has significantly more value than what the continent sells to the wider world – mostly

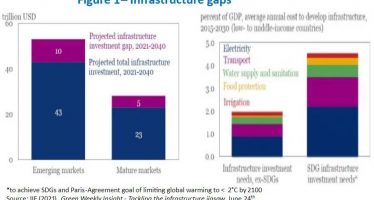

Matchmaking Private Finance and Green Infrastructure

The contrast between the scarcity of investments in infrastructure and the excess of savings invested in liquid and low-return assets

Paul P Andrews: Keeping Up with Fast-Changing Equity Markets

The second annual World Investor Week (WIW) kicked off early October with a global initiative to improve the education and