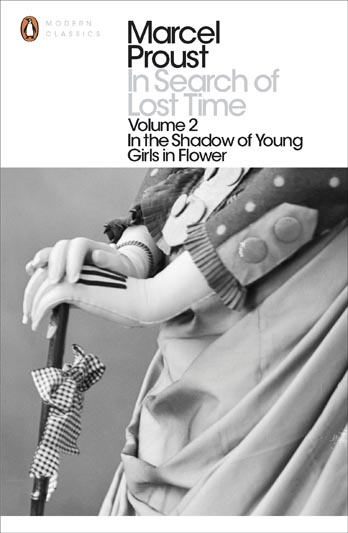

In Search of Lost Time

“Love is a striking example of how little reality means to us.”

A novel in seven volumes with a total page count of well over 4,000, In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu) is reportedly the most voluminous of literary works ever published. Its length, however, does not detract from its quality: Marcel Proust’s masterpiece has been repeatedly hailed as both the most respected and most influential novel of the twentieth century.

A novel in seven volumes with a total page count of well over 4,000, In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu) is reportedly the most voluminous of literary works ever published. Its length, however, does not detract from its quality: Marcel Proust’s masterpiece has been repeatedly hailed as both the most respected and most influential novel of the twentieth century.

Proust enjoyed only a few months of acclaim and recognition for his inestimable contribution to the realm of letters before his death in 1922. Earlier, he had been considered – if at all – a mere trifler in French fin-de-siècle literature or, at best, a coterie writer for the high nobility of Faubourg Saint-Germain. It was only after the first tome of his monumental work appeared in English that Marcel Proust attained a status equal to his literary skills.

Originally titled Remembrance of Things Past – taken from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 30 – In Search of Lost Time (adopted and in common usage since the 1992 revision by Prof DJ Enright) and its author have become cultural icons that bestow social distinction on all those who claim familiarity. However, only a select – and persistent – few actually fully mastered the novel and thus gained access to its marvels.

Readability greatly improved with revised translations that cleaned up some of the flowery Edwardian prose originally employed by Charles Kenneth Scott-Moncrieff who in 1921 quit his job as private secretary to the rather eccentric Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe owner of The Times, to work fulltime on the translation of the text. Though the Scott-Moncrieff translation merits lavish praise for its consistency, it also dulls the original insofar as Proust is at times sharp and coarse in getting to the point where his translator prefers graceful detours and verbose evasions.

Rather than a “purveyor of high-grade cultural narcotics,” the Proust of contemporary translation is one closer to the original. During his lifetime, Proust eschewed the intellectually pretentious forcing his publisher Bernard Grasset to slash the price of his novel, arguing that “people who spend ten francs on a book are generally stupider than those who buy them for three.”

In Search of Lost Time follows a loose, and at times slightly surreal, plot inhabited by a multitude of protagonists whose diverse perspectives and involvements explore the connection between experience, memory, and writing in a way that de-emphasises the outward plot. Not unheard of in contemporary novels, Proust’s approach was nothing short of revolutionary in 1913 when the first volume of À la recherche appeared in print.

| Title | In Search of Lost Time |

| Author | Marcel Proust |

| ISBN | 978-0-8129-6964-1 |

| link | http://www.amazon.com/gp/search?index=books&field-isbn=9780812969641 |

You may have an interest in also reading…

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil

“The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good

The Good Soldier Švejk

“And somewhere from the dim ages of history the truth dawned upon Europe that the morrow would obliterate the plans

If This Is Man / The Truce

“A country is considered the more civilised the more the wisdom and efficiency of its laws hinder a weak man