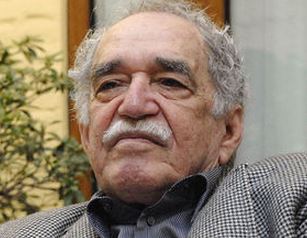

Gabriel García Márquez (1927-2014): A Farewell to the Patriarch of Literature

It is a rare genius who can encapsulate in writing the soul of a country. One who does so with an entire continent is rarer still. Those attributed with such virtuosity tend to be long dead, and most had the good sense not to be born in South America. That did not stop Gabriel García Márquez from leaving an indelible mark on literature.

It is a rare genius who can encapsulate in writing the soul of a country. One who does so with an entire continent is rarer still. Those attributed with such virtuosity tend to be long dead, and most had the good sense not to be born in South America. That did not stop Gabriel García Márquez from leaving an indelible mark on literature.

To condense into novel form all the tempers, colours, and rhythms of such a vast place where every individual component feels somehow ancient yet transplanted, smuggled, stolen even, and haphazardly reassembled on the other side of the world. A continent with a deceptive familiarity, an unrelenting heat, and the tranquil disposition you’d expect from a place founded by men who thought they had found paradise, only to immediately start tearing it apart looking for gold and other riches. Such a literary feat would require a mind as vibrant, as blunt, as melancholic, as magical as the continent itself. It’s that vibrant, blunt, melancholic mind that won Gabriel Márquez the 1982 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Mr Marquez launched his writing career in the early 1950s, after quitting his studies at the National University of Colombia. His first job at El Heraldo in Barranquilla earned him three pesos per article. He went on to become a contributor and film critic for El Espectador in Bogotá. In December of 1957 he accepted a position at El Momento in Caracas just in time for the 1958 Venezuelan coup. That same year he married Mercedes Barcha Pardo who would accompany him for the rest of his life. The following year their first son Rodrigo was born.

Mr Márquez’ literary debut, The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor, was a journalistic expose of a marooned sailor, Alejandro Velasco, from a Colombian naval vessel carrying contraband goods. The following controversy forced him to accept a post as a foreign correspondent in Europe.

After this sojourn, the family settled in Mexico City in 1961, where a few years later Gonzalo, their second son, was born.

Back to the Roots

Since starting out as a writer, Mr Márquez knew he wanted to write a novel based on his childhood in Aracataca, a town near the Colombian Caribbean coast, and the grandparents who raised him. This was to be a novel based on the stories of his grandfather Nicolás Márquez Mejía, a veteran of the Thousand Days’ War and a hero among Colombian liberals, who had shaped Marquez’ political outlook. The novel was also to be rooted in the stories of his grandmother, who conflated the superstitious with the sensible, and the magical with the mundane, all delivered in the same matter-of-fact tone.

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” That opening line finally came to Marquez while driving his family on a vacation to Acapulco. Marquez later tells how he immediately turned the car around, got home and locked himself in a room with four packs of cigarettes, and worked on the book every day for 18 months. The result was A Hundred Years of Solitude; an epic novel telling the story of several generations of the Buendía family from the time they founded the village of Macondo. The book became an instant bestseller going on to sell over 25 million copies worldwide.

The success of A Hundred Years of Solitude was followed by a string of best-selling novels such as Autumn of the Patriarch which recounts the thoughts of a dictator of a fictional Caribbean country who is simply referred to as the General and who serves as an amalgamation of several Latin American and European dictators. He also penned Love in the Time of Cholera, a love story based on his parents’ courtship, as well a number of nonfiction books and short stories.

Upon receiving his Nobel Prize in 1982, Marquez gave a speech entitled The Solitude of Latin America concerning the colonial legacy of the continent and its relationship with the rest of the world.

Public Duty

Márquez held strongly that the writer had a public duty to speak out on political issues, and put his fame to good use. He was a particularly vocal critic of US imperialism, which resulted in him being labelled a subversive and banned from entering the US. In 1975, Gabriel Márquez pledged not to publish again until the Chilean Dictator Augusto Pinochet was deposed, a pledge, as it turned out, he could not fulfil.

His socialist views led him to consistently back the regime in Cuba, and he became a close personal friend of Fidel Castro. His faithfulness to the Cuban revolution led to him falling out with many of his own generation of Latin American writers, who were increasingly critical of the lack of intellectual freedom on the island.

Despite the occasional controversy, Marquez was seen as a man respected by all parties in the region where he is affectionately known as Gabo, even acting as a facilitator in several negotiations between the Colombian government and the guerrillas, including the former 19th of April Movement (M-19), and the current FARC and ELN organizations.

In 2002, Marquez published Living to Tell the Tale which was intended to be the first part of a three volume autobiography. Volumes two and three were never published. In 1999, Gabriel García Márquez was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer. Three years later, his brother Jaime announced that Márquez was suffering from dementia. He was hospitalised in Mexico City for lung and other infections. Mr Márquez died of pneumonia at the age of 87.

This decade marks the bicentennial of independence in many Latin American countries, including Marquez’s own Colombia. Those 200 years have brought revolution, civil war, and military coups. The decolonisation process was also reverted with large swaths of the continent bought up by foreign interests.

As Marquez himself pointed out in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech; the metaphorical nation populated by her forced migrants rivals Norway in size. It is the continent of the Amazon River, of the United Fruit Company and El Dorado, of drug cartels, carnival, and the Andes Mountains. A continent of ancient devotion and superstitions – both indigenous and imported – and of fervent rationalism and ideological dogma (mostly imported).

It is also home to 99 billionaires and counting and host of the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics. It is the continent of Fidel Castro, Pablo Escobar, Christiana Figueres, Pope Francis, José Mujica, Augusto Pinochet, Carlos Slim, and Diego Rivera. It is the continent of Gabriel García Márquez. This very well may be the century that the region finally finds stability and prospers, but that hope could just as easily be the naïve optimism of the contemporary. If we are to have a hope of understanding that future we must discover the place and its people by its own terms. These are the terms of Gabo himself.

About the Author

John Marinus, who also contributes to our Editor’s Heroes section, is a freelance writer based in the Netherlands.

John Marinus, who also contributes to our Editor’s Heroes section, is a freelance writer based in the Netherlands.

You may have an interest in also reading…

How Bernard Arnault Turned One Franc Into a Dynasty

French billionaire Bernard Arnault’s off-beat approach to business would be hard to replicate By KITTY WENHAM It started with one

BRIC Stocks Now Out of Favour … Later to Be an Incredible Investment Opportunity

With BRIC stock valuations currently low and yet with strong long term projected growth a great buying opportunity may materialize

Nicholas Brady: Soccer Finance and the Pragmatist Who Fixed a Debt Crisis

Back in the days when a top-scoring soccer player could be enticed for a few million, Brazilian attacker Romario set