World Bank Group: A Promising New Resource for Development – The Potential of Sovereign Wealth Funds

Norway: Storting building

Mobilizing finance for long-term, large-scale direct investment in development is a daunting global challenge. However, a growing and potentially vast source of capital seems poised to transform the process of financing development, reducing poverty and building shared prosperity in some of the world’s lowest-income countries. The wealth controlled by Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs), which now command almost $5 trillion in assets, seems destined to become a vital new force in the global financial architecture.

Already deploying more than twice the sum controlled by the world’s private-equity industry, SWFs – if wisely managed and well governed – could emerge as a key driver of global development as their capital is put to work in far-sighted investment opportunities.

SWFs are government investment agencies, usually established with balance-of-payments or fiscal surpluses – which are frequently created by an influx of revenue from commodity exports. Since SWFs are often motivated by an implicit promise to serve the long-term welfare of their countries’ citizens, their ideals coincide with those of the global development community, which seeks to allow capital to be put to work in ways that will optimize human development, social welfare and sustainable growth. Given their potential for providing substantial South-to-South flows of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), SWFs could be a vehicle that delivers “win-win” outcomes – earning substantial returns for their countries, while channelling savings in surplus-earning countries toward productive investments that benefit the poorest people.

“Many governments are encouraging their SWFs to increasingly invest in domestic industries and infrastructure projects.”

The long-established SWFs of resource-rich countries of the North Sea and Persian Gulf, and of fast-developing financial centres like Singapore, may be today’s best-known investment vehicles, but the SWF landscape goes far beyond the likes of the Government Pension Fund Global of Norway (with more than $700 billion in assets) or Temasek (with about $175 billion). A wave of new SWFs has been set up in recent years – with more than 20 founded since 2005 – thanks to booming prices for commodities exported by developing countries, largely due to new resource discoveries and increasing consuming-country demand for imports. As SWFs become ever more influential, a new array of financial decision-makers is assuming a prominent position on the global stage.

New Funds

Papua New Guinea, for instance, established a SWF in 2012 to invest funds from that island nation’s mineral, oil and gas exports. Nigeria, the largest producer of oil in Sub-Saharan Africa, in 2011 set up a sovereign wealth fund – managed by the Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority – that has three priorities and thus deploys its assets in three separate compartments: a Stabilization Fund, a Future Generations Fund, and a Nigerian Infrastructure Fund. Nigeria is part of an SWF movement that is increasingly prominent throughout Africa: In the Sub-Saharan region, 31 countries are already dependent on hydrocarbons or mineral resources for more than 25 percent of their merchandise exports – and thus they, along with other countries that continue to discover resource riches, seem likely to deploy their funds through SWFs.

The investment choices of SWFs can have far-reaching impact. SWFs in developed countries optimize their portfolios based on their own objectives and risk/return and investment-horizon profiles. These characteristics may lead to investments in long-term development projects in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDEs).

SWFs in resource-rich EMDEs also optimize their portfolios using similar criteria, which may lead to investments in long-term development projects in host countries themselves or in other EMDEs. For many resource-rich developing countries that do not yet have access to global capital markets or are only now emerging onto the global economic stage, revenues from natural resources can provide an important means to finance investments in such public goods as education and infrastructure.

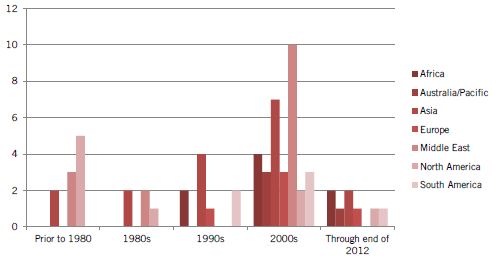

Chart 1: Sovereign Wealth Funds

Domestic Industry and Infrastructure

Many governments are encouraging their SWFs to increasingly invest in domestic industries and infrastructure projects. Recent examples include the infrastructure fund compartment managed by the Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority as well as the Angolan SWF, the Fundo Soberano de Angola. This is an understandable course, so long as the investments themselves are directed to projects with positive financial and economic returns and so long as the macro-fiscal and governance risks inherent in making domestic investments is adequately mitigated.

However, SWFs in resource-rich low-income countries face challenges of governance and transparency that can inhibit their ability to contribute to and realize returns on investments in long-term development projects. Resource-rich developing countries that face high levels of poverty and privation will surely need to manage their wealth carefully, recognizing that their natural resources are likely to be exhaustible. Moreover, upholding strong standards of governance and designing responsible investment policies will be critical to maximizing their long-term investment opportunities and thus supporting sustained prosperity.

Looking toward their long-term needs, stewards of SWFs would be wise to seek far-sighted counsel from a range of trusted sources that can provide strategic support beyond the advice available from investment banks, consulting and law firms, and asset-management firms.

One such resource to which developing country SWFs can turn for support is the World Bank Group, whose long-term priorities for poverty reduction and sustainable development are in harmony with developing countries’ hopes to soundly manage their resource wealth. Taking a holistic view of each country’s development needs, and focusing on positive long-term outcomes, is essential to making the most of each SWF’s potential.

Since the World Bank Group carries on a sustained policy dialogue with the government institutions that typically own, manage or oversee SWFs – usually a country’s Ministry of Finance or Central Bank – it is well-positioned to offer strategic counsel, providing expertise in the political-economy implications of SWF-related decisions and detailed knowledge of global best practices.

Management and Oversight

At every stage of SWF management and oversight – from weighing whether an SWF is an appropriate vehicle within the context of each country’s local conditions, to drawing up governance rules and investment policies that uphold strong international standards – the World Bank Group can be a partner with governments in working through the many challenges that accompany SWF decision-making. Such issues can include judging the macroeconomic context within which an SWF is formed; weighing an SWF’s strategic objectives and realistic goals; aligning the institutional and governance arrangements of the fund; and considering domestic investment strategies.

“In addition, the World Bank Group in 2012 established a secretariat and advisory group to assist SWF leaders worldwide, assembling experts and mobilizing knowledge resources from across the Bank.”

Recognizing the growing potential of SWFs in influencing the contours of development, the World Bank Group has structured a series of mechanisms to help serve the needs of SWFs with assets available for development investing. Within the International Finance Corporation – the private-sector investment arm of the World Bank Group – the IFC’s Asset Management Company now controls about $6.5 billion in assets, with six funds that can co-invest with SWFs and pension funds. For example, the African, Latin American and Caribbean (ALAC) Fund, was set up in 2010 to provide SWFs and pension funds with an opportunity to co-invest with IFC in growth equity investments in developing countries. The portfolio of the $1-billion, 10-year ALAC Fund is now about 40-percent focused on sub-Saharan Africa, with investments in several countries, including Nigeria, Kenya and Uganda.

In addition, the World Bank Group in 2012 established a secretariat and advisory group to assist SWF leaders worldwide, assembling experts and mobilizing knowledge resources from across the Bank. By coordinating its engagement with SWFs, the advisory group aims to provide an integrated value proposition for the World Bank Group’s clients and to encourage knowledge-sharing. The group reviews draft SWF laws; helps design SWF-related engagements; and facilitates knowledge-exchange about SWFs. With a cross-sector perspective, the secretariat taps into a broad set of experts and considers cross-cutting issues related to SWF design and implementation.

Knowledge and Needs

Pursuing a vigorous knowledge programme, the group has generated case studies on SWFs and has set up an online platform that will be accessible to SWFs, academic hubs and external practitioners by June 2014. A series of workshops, led by experts who have set up or managed SWFs, has begun helping practitioners build their capacity. Those workshops are expected to be available to SWF leaders who will attend the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) spring meetings in April and annual meetings in October.

In prioritizing the needs of SWFs, the World Bank Group joins other international organizations that have been stepping up their work on SWF-related issues in the context of global development. The IMF also has a longstanding advisory role with the SWF community, having spearheaded the development of the Santiago Principles – voluntary guidelines on SWF best practices – in 2008. An UNCTAD panel on SWFs at the Doha Roundtable in April 2012 sought to explore the potential for SWF investments to promote sustainable development. A Global Sovereign Funds Roundtable in May 2012 focused on development investing and Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) principles.

With optimism running high about the prospects for global development, governments and international institutions are focused on the post-2015 agenda, beyond the fulfilment of the Millennium Development Goals process. As new actors and new investment vehicles seek to drive development forward, well-managed and well-governed sovereign wealth funds seem likely to be an ever-more-important resource in promoting transformational projects that will help fulfil the global goals of eliminating extreme poverty and promoting shared prosperity.

About the Authors

Shanthi Divakaran

Shanthi Divakaran is a senior financial sector specialist in the World Bank’s Financial and Private Sector Development Network. She currently manages the World Bank’s Sovereign Wealth Fund secretariat.

Christopher Colford

Christopher Colford is a communications officer at the World Bank’s Financial and Private Sector Development Network. Mr Colford was previously a consultant at Hill & Knowlton Public Affairs Worldwide and a senior editor at McKinsey & Company.

You may have an interest in also reading…

CFI.co Meets Juan Pablo Córdoba Garcés

Mr Córdoba Garcés assumed his current position as CEO of the Colombian Securities Exchange in March 2005. Since then his

Otaviano Canuto: Macro-economic Policy Change – We’re Not in Kansas Any More

The possibility of multiple financial shocks lies ahead. Three significant changes to the macro-economic policy regime in advanced economies have

World Bank MD and CFO Anshula Kant: Financing Where It Matters Most

Financing Where It Matters Most — People, The Planet, and the Role of Investors Amid overlapping crisis facing the world,