Lord Waverley and Paul Baker: The Promise, Potential and Pitfalls of Britain’s Relationship with Africa

The concept of Africa Rising is truer today than ever. Despite the pandemic disruption that has caused the continent’s first negative output growth in 27 years, Africa’s performance over the past decades has been remarkable.

Many African countries have made significant improvements in terms of business environment and overall macro-economic performance, creating opportunities for growth and development.[1] In Ethiopia, gross domestic product and per-capita purchasing power parity have increased by 150 percent since 2009.[2] The technological advances brought about by the Fourth Industrial Revolution are allowing Africa to address some of its major challenges.

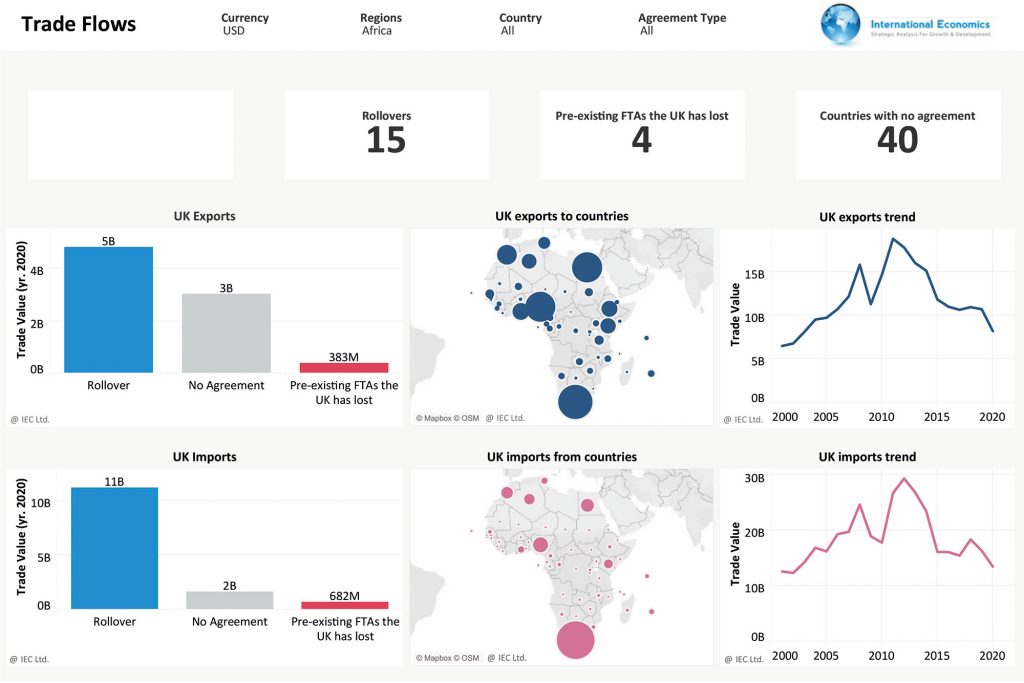

Figure 1: UK Trade with Africa, 2020. Source: IEC; UNSD; DIT

In the health sector, countries like Rwanda and Ghana are deploying drones to deliver medication, blood products and medical supplies to remote areas. In financial services, the fintech industry is transforming lives in rural and urban areas.[3]

There have also been significant improvements in leadership and governance; citizens are demanding accountability from their leaders and institutions. From 2008 to 2017, the Mo Ibrahim Foundation highlighted 34 African countries that improved national governance. As highlighted by Signe, since 2016 meaningful elections have led to changes in Benin, Comoros, Ghana, Lesotho, Liberia, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Sierra Leone.[4]

Africa’s ambitions are growing, too, through the vision of a pan-African common market. Africa Vision 2063 states that the continent aims to become “integrated, prosperous and peaceful”, driven by its citizens and representing a dynamic force in the international arena.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) represents the latest step towards that objective. Originally foreseen in the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community (AEC Treaty), the potential of the AfCFTA is huge. With 54 contracting parties, it brings together more than a billion people and a combined GDP of some $2.6tn. That has the potential to lift 30 million people from extreme poverty and 68 million from moderate poverty. It could also increase real income gains by seven percent by 2035.[5]

Open markets for African goods and services, increased mobility and the reallocation of resources should lead to economic and industrial diversification, structural transformation, technology improvement and a boost for human capital.[6] AfCFTA can pave the way to prioritised, strategic investments in sectors with a comparative advantage, fostering development of industries that could make African businesses regional and international players. Increased regional integration from the agreement is expected to increase the economic diversification.

However, in order to multiply the benefits, a comprehensive vision of trade and development is needed.

In this context, the UK has the potential to be Africa’s partner-of-choice for trade, investment and development. Promoting a rules-based trade system, forging investment and advancing partnerships and technology between the UK and Africa, has potential for both sides. A lot of work must first be done to reinvigorate the existing commercial ties.

Trade and investment between the UK and Africa have barely advanced over the past decade, even before the pandemic hit. A report by the Select Committee on International Relations and Defence says, “there has been ‘a flatline’ in UK trade with, and investment, in Sub-Saharan Africa”.

The stock of UK foreign direct investment was only £2bn more in 2018 than in was in 2008. The UK was the fourth-largest source of FDI to Africa in 2017, accounting for six percent of FDI stock.[7] The UK does not have any trade agreement with 40 of the African nations, and has rolled-over the EU’s former trade agreements with 15 African nations. It has lost the former EU trade agreements with four of those nations, and there is a lot of catching-up to do.

The UK will also have to compete with established and emerging partners. China, specifically, has used its Belt and Road Initiative to strengthen its presence by investing in 52 of the 54 African countries. It is poised to enter the 53rd in Sao Tome and Principe.[8] China’s FDI stock in Africa totalled $110bn in 2019, contributing to some 20 percent of Africa’s economic growth.[9]

The UK should also take note of the efforts of the EU, one of Africa’s traditional development partners, which in 2020 issued its EU-Africa Strategy. This aims to boost economic relations, create jobs, and deepen the EU-Africa partnership.

The future of Africa does have some risks and roadblocks. The pandemic has highlighted some of them, including the urgent need to enhance health systems and increase emergency planning and preparedness. Supply chains that rely on just-in-time deliveries have been disrupted, prompting some nations to impose restrictions to combat shortages of pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, food, technology, and natural resources.[10]

Poverty in Africa remains stubbornly high, with 437 million of the world’s poorest people merely surviving in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 10 of the world’s 19 most unequal countries are. By 2030, the World Bank forecasts that Africa could be home to 90 percent of the world’s poor.[11]

The AfCFTA will not be a panacea for Africa’s trade and integration barriers. Non-tariff measures, unaffordable intra-continental transport costs, poor connectivity, and weak infrastructure remain challenges for coming years. It is more expensive to send a parcel from Mauritius to continental Africa than it is to do so from France, China, India or even Brazil. Peace remains fragile, as do Africa’s relatively young democracies.

But growth prospects are substantial, and the UK-Africa investment summit this year testifies to that. Brexit represents an opportunity for Africa to strengthen its ties with the UK.[12] Britain can, and should, position itself as powerhouse for services, investment environment, standard-setting and governance. But a comprehensive and detailed strategy is needed to address the African continent’s challenges and needs. Trade ties with the AfCFTA parties must be strengthened to reduce tariff barriers, minimise non-tariff measures, and harmonise domestic regulations and regulatory practice.

Further negotiations between standard-setting bodies should take place, with support for British firms exporting to Africa and for African firms exporting to the UK. The UK should reinvigorate its position as a source of FDI to build the necessary capacities for Africa to thrive.

Africa: much to do, much to be gained — for all.

About the Authors

Lord Waverley is a Member of the House of Lords and the founder of SupplyFinder.com.

Paul Baker is CEO of International Economics Consulting.

References

[1] Sangafowa Coulibaly, B. (2017). Is Africa Still Rising? Brookings, October 6. Available from: brookings.edu/opinions/is-africa-still-rising/

[2] Oqubay, A. (2020). Will the 2020s be the decade of Africa’s economic transformation? Overseas Development Institute, January 14. Available from: odi.org/en/insights/will-the-2020s-be-the-decade-of-africas-economic-transformation/

[3] Signe, L. (2021). US trade and investment in Africa. Brookings, July 28. Available from: brookings.edu/testimonies/us-trade-and-investment-in-africa/

[4] Signe, L. (2020). Unlocking Africa’s Business Potential: Trends, Opportunities, Risks, and Strategies. Brookings Institution Press, ISBN 9780815737391.

[5] WB (2020). The African Continental Free Trade Area: Economic and Distributional Effects. The World Bank Group

[6] UNCTAD (2015). The Continental Free Trade Area: Making it work for Africa, UNCTAD Policy Brief No. 44, December, p. 1.

[7] UK Parliament (2020). The UK and Sub-Saharan Africa: prosperity, peace and development co-operation. Select Committee on International Relations and Defence. Available from: publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5801/ldselect/ldintrel/88/8802.htm

[8] Venkateswaran, L. (2020). China’s belt and road initiative: Implications in Africa. ORF Issue Brief No. 395, August 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

[9] Ze Yu, S. (2021). Why substantial Chinese FDI is flowing into Africa. London School of Economics. Available from: blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2021/04/02/why-substantial-chinese-fdi-is-flowing-into-africa-foreign-direct-investment/

[10] Government of Canada (2021). Minister of Foreign Affairs – Transition book. Available from: international.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/briefing-documents-information/briefing-books-cahiers-breffage/2021-01-fa-ae.aspx?lang=eng

[11] Chakravorti, B. & Chaturvedi, R. S. (2019). Research: How Technology Could Promote Growth in 6 African Countries. Harvard Business Review, December 04. Available from: hbr.org/2019/12/research-how-technology-could-promote-growth-in-6-african-countries

[12] Graham, S. (2021). Perspectives on post-Brexit Africa-UK trade: Opportunities and Challenges, in Thuynsma, H. A. (eds). Brittle Democracies? Comparing Politics in Anglophone Africa, ESI Press.

You may have an interest in also reading…

European Investment Bank: Investment Plan for Europe

Investment Plan for Europe – Paradigm Shift in the Use of Public Resources The Marshall Plan did much to inject

World Bank Group: Ask Citizens Where Public Money Should Go – The Surprising Results

As citizen engagement gains traction in the development agenda, identifying the extent to which it produces tangible results is essential.

Women’s Brain Project – Shattering the Status Quo: Investing in Women in STEM

Representation matters. The now classic TV show The X-Files starring David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson inspired more women to pursue