Ann Low, US Department of State: Good Corporate Governance is Good Business

OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises.

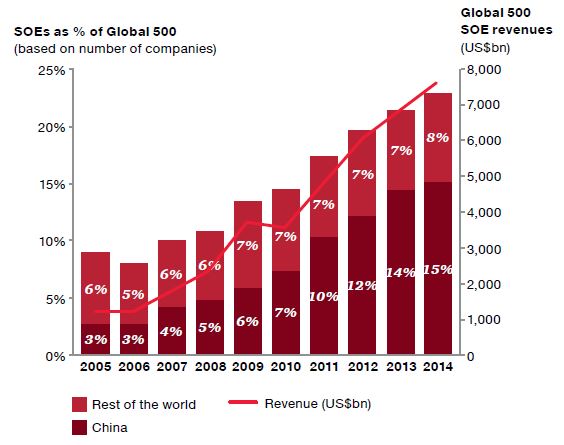

Over the past decade, cross-border trade and investment by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) has surged. According to the OECD, whereas in 2005, there were only three SOEs in the Fortune Global 50 list of the largest companies in the world, in 2013, there were 11 [1]. This came about mostly from the growth of emerging market economies, where SOEs are often dominant economic actors and are now seeking to expand abroad.

Over the past decade, cross-border trade and investment by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) has surged. According to the OECD, whereas in 2005, there were only three SOEs in the Fortune Global 50 list of the largest companies in the world, in 2013, there were 11 [1]. This came about mostly from the growth of emerging market economies, where SOEs are often dominant economic actors and are now seeking to expand abroad.

For example, in 2001, China launched its Go Global Strategy, which significantly increased foreign investment by its SOEs [2]. However, increased international activities by SOEs have raised questions about government influence, potential trade distortions, and unfair competition. In their home countries, SOEs are often exempt from laws and regulations that govern private enterprises, and may have advantageous access to land, government procurement opportunities, or borrowing.

“According to the OECD, whereas in 2005, there were only three SOEs in the Fortune Global 50 list of the largest companies in the world, in 2013, there were 11.”

Such advantages, especially preferential access to financing, may be perceived as conferring a competitive advantage to SOEs in their international operations [3]. The newly updated OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises provide a reference point to address a number of challenges associated with SOEs competing in the marketplace.

SOEs are frequently in the news – and too often, the news is bad. From allegations of graft against Petrobras in Brazil, to concerns about lack of transparent reporting by Indian state-owned banks, to reports of asset misallocation and irregular practices by a number of European electricity companies, some intrinsic problems within the sector seem evident. SOEs pose distinct corporate governance challenges because their management may be protected from two disciplining factors that are considered essential for policing management in private sector corporations, i.e. the possibility of takeover and the possibility of bankruptcy [4].

Complex Chain of Agents

More fundamentally, corporate governance difficulties derive from the fact that the accountability for the performance of SOEs involves a complex chain of agents (management, board, ownership entities, ministries, the government), without clearly and easily identifiable principals [5]. On the one hand, SOEs may suffer from undue hands-on and politically motivated ownership interference, leading to unclear lines of responsibility, a lack of accountability, and efficiency losses in the corporate operations.

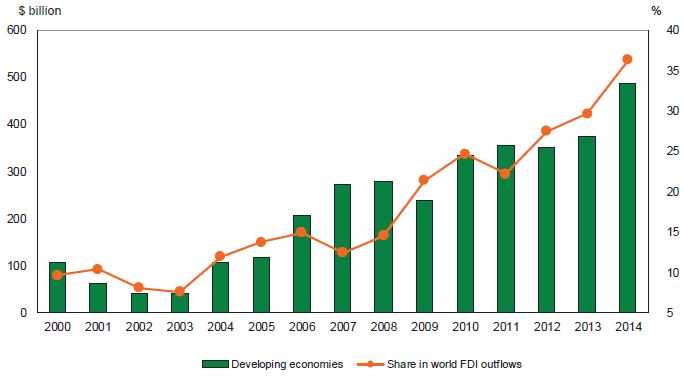

Figure 1: Developing economies – FDI outflows and their share in total world outflows, 2000-2014 (Billions of US dollars and per cent).

Note: Excluding Caribbean offshore financial centres. Source: UNCTAD, Global Investment Trends Monitor, No. 19, May 2015.

On the other hand, a lack of oversight due to totally passive or distant ownership by the state can weaken the incentives of SOEs and their staff to perform in the best interest of the enterprise and the general public who constitute its ultimate shareholders. This can raise the likelihood of self-serving behaviour by corporate insiders [6]. As a result, SOEs may be more likely than private corporations to fall prey to corruption and mismanagement.

This can change. In 2015, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Working Party on State Ownership and Privatization Practices – which comprises the 34 members of the OECD, 13 non-members, including G20 countries such as Argentina, Brazil, China and South Africa, and an observer from the World Bank – completed a two-year long negotiation to update the 2005 OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises. The revision process, initiated in 2013, involved extensive consultations with governments, business and labour representatives, and civil societies from across the world.

The revised guidelines are recognised globally as the principal guidance for corporate governance of SOEs. The guidelines are compatible with the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance on which they are based. They bring to the SOE sector a high level of corporate governance for commercially-oriented SOEs similar to that required of publicly-traded companies.

The guidelines provide recommendations to encourage efficiency, transparency and accountability in the SOE sector. They call on SOEs to be leaders in responsible business conduct, and they empower citizens to ask their governments for clear statements explaining the purpose, costs and benefits of state-ownership. The guidelines are addressed to government ownership entities, which exercise the shareholder function, but they also should be read by board members and managers of SOEs, as well as advocacy groups promoting good governance.

SOE Reforms

In the recent past a number of OECD countries and Asian economies, including China, have sought to reform their SOE sectors, or are in the processes of doing so. Many cite the guidelines as a point of inspiration. Notably, the government of the Republic of Korea has recently mandated that the revised guidelines be implemented on a whole-of-government basis. A number of OECD members are further in the process of publicizing the guidelines widely to encourage adherence globally, and several countries are translating them into local languages.

Figure 2: SOEs in the Fortune Global 50. Note: SOEs defined as having 50% or more government ownership.

Source: Pwc, “State-owned enterprises: Catalysts for public value creation?” April 2015.

Implementation of the 2015 guidelines can help ensure that cross-border investments by SOEs do not distort markets, and that SOEs effectively contribute to their own country’s economic growth. Where implemented, the guidelines will help level the playing field between SOEs and private enterprises by increasing transparency and accountability. They may reduce market volatility caused by inadequate corporate governance and insufficient disclosure. Finally, they will empower stakeholders, giving them more information to hold their governments accountable and judge whether state-ownership of a particular enterprise is an efficient allocation of resources and whether it achieves other desirable social goals.

The new OECD guidelines bring four fundamental changes to the original 2005 guidelines:

- There is a new introductory section on Applicability and Definitions, which includes a broad definition of SOEs. For the purpose of the guidelines, an SOE is any corporate entity recognised by national laws as an enterprise and in which the state exercises ownership. The guidelines distinguish between ownership and control. They apply to SOEs where the government exercises control, which can be the case even when the State is a minority shareholder. The guidelines are generally not intended to apply to entities or activities whose primary purpose is to carry out a public policy function, even if the entities concerned have the legal form of an enterprise.

- There is a new chapter about defining and communicating the rationales for state-ownership of enterprises. The guidelines recommend that states “carefully evaluate and disclose the objectives that justify state ownership and subject these to a recurrent review.” Governments should “consider whether a more efficient allocation of resources to benefit the public could be achieved through an alternative ownership or taxation structure [7].” Governments should use the goal of maximising value for society through an efficient allocation of resources as the yard stick for measuring an SOE’s effectiveness. Any public policy objectives that SOEs are required to achieve should be clearly mandated and disclosed.

- The previous Chapter 1 of the 2005 guidelines became a broader chapter on SOEs in the marketplace to address competition in greater detail. Addressing the situation where SOEs compete with other firms in the marketplace, it includes practical guidance on the cost and conditions of SOE financing, rate-of-return requirements, and public procurement procedures.

- Finally, the OECD Working Party on State Ownership and Privatization Practices brought responsible business conduct into the guidelines and recommended SOEs adhere to international standards and best practices, such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. New features include a recommendation to eliminate political donations by SOEs, clearer language on disclosure standards and board practices, strengthened text on public-private partnerships and the management and disclosure of related risks, and stronger text on corporate ethics and anti-corruption.

The revised OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of SOEs, along with other OECD instruments, present key points on efficient allocation of resources, fair competition in the marketplace, and responsible business conduct that governments are encouraged to incorporate in their SOE reform efforts.

Adherence to the OECD guidelines is important since they provide the underpinning for open markets and fair competition, where all well-run businesses can succeed. The United States, the OECD Working Party on State Ownership and Privatization Practices, the OECD, the Business and Industry Advisory Committee to the OECD (BIAC), and the Trade Union Advisory Committee to the OECD (TUAC) join together to encourage all governments, SOE board members, and managers of SOEs to read the guidelines and apply them. Good corporate governance is good business. i

To read the guidelines, visit: www.oecd.org/daf/ca/soemarket.htm

About the Author

Ann Low is Deputy Director of the Office of Investment Affairs at the U.S. Department of State, and Vice Chair of the OECD Working Party on State-Ownership and Privatization Practices. She led the U.S. team negotiating the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises.

References

[1] http://fortune.com/global500/ and OECD Corporate Governance Working Papers, No. 14: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/oecd-corporate-governance-working-papers_22230939.

[2] http://en.people.cn/200401/07/eng20040107_132003.shtml and CSIS Freeman Briefing 5/27/2008, “Issue in focus: China’s Going Out Investment Policy. http://csis.org/files/publication/080527_freeman_briefing.pdf

[3] OECD Corporate Governance Working Papers, No. 14: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/oecd-corporate-governance-working-papers_22230939, p. 13-14

[4] OECD GUIDELINES ON CORPORATE GOVERNANCE OF STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES: 2015 EDITION, p.12, http://goo.gl/TQpmUp

[5] OECD GUIDELINES ON CORPORATE GOVERNANCE OF STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES: 2015 EDITION, p.12

[6] OECD GUIDELINES ON CORPORATE GOVERNANCE OF STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES: 2015 EDITION, p.12

[7] OECD GUIDELINES ON CORPORATE GOVERNANCE OF STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES: 2015 EDITION, p.30

You may have an interest in also reading…

Dieck-Assad, Academic at the Heart of Government

Dr. Maria de Lourdes Dieck-Assad is the rector of EGADE, one of Latin America’s leading business schools. It is always

Lagarde on the Prerequisites for a Strong Global Economy

Extracts from a Speech to the Washington Foreign Law Society by Christine Lagarde, Managing Director, International Monetary Fund (June 4th

GPF Aims To Be the Leader in ESG Investing and Initiatives in Thailand

Under the leadership of Mr Vitai Ratanakorn, Secretary General, Thailand’s Government Pension Fund (GPF) has taken a new approach to