Ian Fletcher, Director IBM IBV: The Trust Economy – What’s My Data Worth?

How Do Organisations Ensure We Get a Fair Return?

The driving force behind “stakeholder capitalism” – the theme of this year’s World Economic Forum meeting at Davos – is the conviction that businesses should balance the needs of all their stakeholders rather than explicitly favouring investors. I believe that’s a particularly apt reminder in the data-rich universe we inhabit today. Data is growing at a seemingly unstoppable exponential rate, as we leave indelible digital fingerprints on everything we touch; indeed, it’s now widely regarded as one of the world’s most valuable assets. But there’s mounting concern that some of the stakeholders who generate that data aren’t reaping their rewards.

In the right hands, data becomes a tool for the greater good, helping to unearth cures for previously incurable diseases, improve communications and create innovative services that enrich our lives. In the wrong hands, it becomes a weapons-grade technology, influencing our actions through the use of behavioural science and sentiment analysis, with machines predicting our every move. So it’s time that we – the real owners of our personal data – reflect on its true worth and the potential ramifications of its misuse. It’s also time that senior executives ensure we get a fair return on the data we share. IBM’s latest Global C-suite Study shows what’s required.

From Pervasive to Persuasive

Data is changing the way we live. Algorithms know what we do and where we do it, what we think and how we feel. In fact, they may even know us better than ourselves. They can be used to make product recommendations, personalise the prices of big-ticket items and nudge our purchasing choices, sometimes so subtly that we are unaware of being influenced. Increasingly, they also make important decisions on our behalf. It’s becoming almost commonplace for enterprises to ask their customers to trust a bot or an algorithm to determine whether they get insurance cover or a mortgage.

Used benignly, data enables organisations to fulfil people’s genuine needs and desires. But not all organisations are benign. Both governments and corporations have been guilty of intrusive surveillance. And in what are arguably the worst abuses, personal data has been utilised to manipulate the political choices people make, threatening the very foundations of democracy. Pervasive intelligence is evolving into persuasive intelligence – and persuasive intelligence can be put to positive or pernicious ends.

“It’s time that we – the real owners of our personal data – reflect on its true worth and the potential ramifications of its misuse.”

So it comes as no surprise that many individuals are becoming increasingly reluctant to part with their personal data. In one recent survey, for example, the majority of respondents had little or no idea how much governments and companies knew about them, didn’t trust governments or companies to handle their data “properly” and didn’t believe that they were getting a fair trade for the data they shared [1].

This rising wariness on the part of citizens and consumers has profound implications for politicians and business leaders everywhere. Our personal data belongs to us, but institutions and corporations often function as its custodians. Senior executives and public servants must thus be able to demonstrate that they will treat our data ethically, protect it effectively and give us a reasonable share of the value they derive from it. They must show, in short, that they are deserving stewards of our data.

Data and Trust Entwined

In the 20th edition of the Global C-suite Study, “Build Your Trust Advantage”, the IBM Institute for Business Value (IBV) set out to explore what’s needed to lead in a world brimming with bytes. The IBV discovered that data has become inextricably entwined with trust. The widespread erosion of trust, on the part of consumers and B2B customers alike, has changed what organisations can – and should – do with data. It’s also transforming the value equation. Where data alone was once an enterprise’s unparalleled asset, it must now factor in transparency and integrity. Data matters, but trust determines its worth [2].

The IBV interviewed 13,484 C-suite executives from 20 industries and 98 countries, with surprising results. During the course of its research, the study team identified an elite group of just 9 percent of respondents whose organisations are data leaders. The IBV refer to them as Torchbearers, this group excel at innovating and managing change. They have also surpassed their peers in terms of revenue growth and profitability.

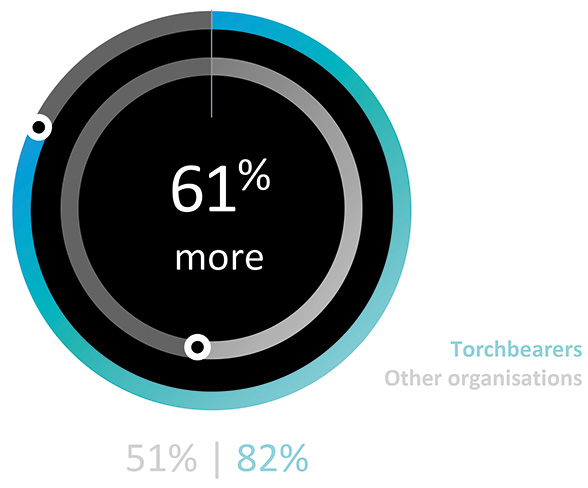

So what accounts for this stellar performance? The Torchbearers have fused their data strategy with their business strategy and operate in a data-rich culture. They also set the bar high for the value they expect to gain from data and typically exceed their targets. But what’s most notable of all is that they put customer trust centre stage – in marked contrast with the organisations represented by the rest of the interviewees (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The power of trust. Torchbearers focus on using data to strengthen their customers’ trust.

Past the Tipping Point

The trust customers once gave, almost blindly, to brands and institutions has been slipping away for some time now. Data sharing among organisations has also become constrained by a mutual lack of trust. Witness the fact that 36 percent of B2B buyers in a recent survey didn’t believe they “got the full picture” from their vendor during the sales process [3].

The IBV’s analysis suggests that trust has passed its tipping point. All organisations face a future in which changing customer sentiment and new regulations could severely constrain their access to prized personal data. But the most advanced enterprises recognise that, if they want to enjoy the huge revenues that new business platforms and the application of artificial intelligence could provide, they will have to build – or rebuild – customers’ faith in them.

“Just 9 percent of the senior executives the IBM IBV interviewed head organisations that are data leaders and put customer trust centre stage.”

An organisation’s ability to earn a trust advantage depends on how good it is at creating trust in data and how well it engenders trust from data. Three basic principles – transparency, reciprocity and authenticity – guide the way Torchbearers handle data and how they engage their customers.

A Clear View

The first requirement is transparency. Customers demand transparency of data associated with products and services and, in the case of personal data, assurances that it’s kept safe and used in a fair manner. Their purchasing decisions depend on detailed product information: data about how products are manufactured and under what conditions, reviews from users and influencers, accreditations from third parties and more.

Brands must prove their credentials. Often, that proof takes the form of customer reviews or buyer testimonials. But some organisations are also turning to blockchain networks, where they can verify that they have honoured their brand promise, whether that promise is speed of delivery, eco-friendly sourcing and manufacturing or anything else. Transparency constitutes evidence that an organisation and its offerings are what the organisation claims they are. Endorsements, coupled with detailed and visible information about the safety and quality of goods, go a long way in establishing trust.

The Rule of Reciprocity

Reciprocity is equally vital. Most C-suite executives understand that to get access to data, they have to give something meaningful in return. The challenge? Organisations often don’t know what their customers would consider a fair exchange. Moreover, customers sometimes have mixed feelings about the benefits to be gained by sacrificing their privacy. Unpublished research by the IBV shows that only three in ten consumers feel strongly that the risks outweigh the rewards.

Answering for Their Actions

The last element is accountability. This covers a broad range of issues, including respect for customers’ privacy and a commitment to data security. The Torchbearers prioritise data privacy: 45 percent see it as a top competitive advantage, second only to customer relationships. But it can be very difficult to discern precisely where customers draw the line. Take personalised car insurance premiums based on telematics. What one customer perceives as added value may seem like “big-brother” scrutiny to another.

Data security can, likewise, be a vexed issue. It’s clearly imperative that all organisations establish policies to combat cyber risk and protect customers. Yet security has become something of a tug of war – a battle between the need to create frictionless customer experiences and the need to authenticate transactions. Excessive caution impairs customer engagement, while too little caution endangers an organisation’s reputation and destroys customers’ trust in it, if their data is hacked.

That said, a good data privacy policy can shield organisations from the worst of the fallout from a data breach by offering customers transparency and opt-out control over their personal information. Conversely, a flawed policy can exacerbate the problems. In one study of Fortune 500 companies, firms that failed to explain their data privacy practices saw their share prices drop sharply when they experienced a data breach, whereas firms that provided customers with a high level of control saw no significant change in their share prices [4].

The Case for Self-control

Today, customers demand transparency about how their personal data is being used; tomorrow, they may insist on exerting full control over the information. People know that their data is being used, but they don’t necessarily know how, where or for what purpose. They are becoming more guarded about what they share and, if businesses cannot convincingly demonstrate the value their customers get in exchange, those customers will insist on recovering their privacy.

Some organisations, anticipating what they consider inevitable, are already making that possible with self-sovereign identity models. Self-sovereign identity puts the management of private data in the hands of individual customers and trading partners. Users supply proof of their identity in the form of digital attestations from the pertinent authorities. They can also pre-programme permission for their data to be used by different entities in different situations, including granting permission to use it for analytics.

“Get it wrong, we risk trapping ourselves in a ‘matrix’ of our own making.”

But the crucial point is that users retain control of their data, in much the same way that people retain control of their own birth certificates and passports. Users can also choose which piece of data to share when they are required to confirm a particular claim. So, for example, an individual who needs to prove that he or she is qualified to drive could provide a statement to that effect, endorsed by the relevant agency, rather than a driver’s licence with all its additional details. The requester gets what it needs to know – and nothing more.

Self-sovereign identity models have enormous potential. They can be used by the partners in a supply chain or an industry alliance to encourage data sharing with accountability, or by airlines and other organisations cross-sharing data through industry alliances. They can also facilitate ‘just-in-time identification’ – where, instead of stockpiling personal data, an enterprise keeps the minimum required to identify a returning user and then requests any extra data it needs to execute the next transaction when the transaction is about to take place.

Of course, self-sovereign identity models still require trust, but it’s trust in a diffuse infrastructure rather than a single entity – and blockchain is the technology that makes such an infrastructure possible. It enables multiple organisations to collaborate by forming a decentralised network much like the Internet itself, with private-key cryptography to ensure the confidentiality and integrity of the data.

Big Data, Big Trust

Something certainly has to change. Digital trails are disappearing, as new legislation requires that organisations secure customers’ consent to use cookies and delete their personal data on request. Regulations are also restricting the sharing of data among business partners. In some cases, conglomerates are finding that they can’t even share data among the companies they own.

The problem is particularly acute in industries that have been dependent on third-party data to get closer to end-users. Executives are growing wary of how trustworthy that data might be and wondering whether third-party data, beset by new regulations, will suddenly dry up.

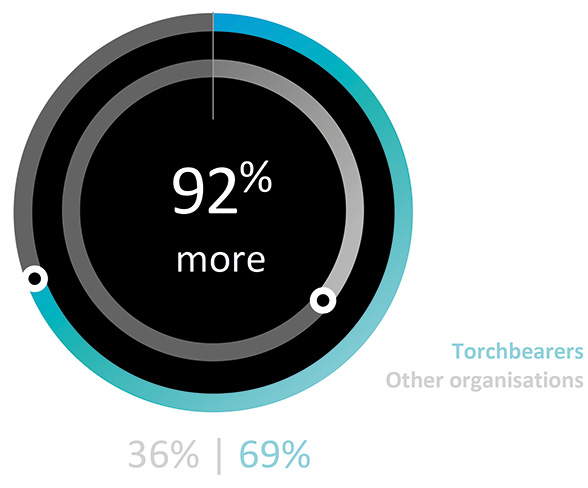

Yet the standouts in the IBV’s study aren’t daunted. Seven in ten Torchbearers already have a treasure trove of reliable, actionable customer data (see Figure 2). The business leaders who head these organisations also realise that trust is integral to its retention. Enterprises that have earned their customers’ trust are better placed both to keep the data they currently hold – since their customers are less likely to demand that it be purged – and to collect more data in the future.

Figure 2: Feast versus famine. Torchbearer C-suites have extensive access to accurate and actionable “360-degree” customer data.

Models For Mutual Benefit

With trust in their data as their guiding light, the Torchbearers are confident of their ability to test new models and enter new markets. New business models have become contingent on access to ever-bigger, ever-broader data. But some of the innovations made possible by new technologies seem just as likely to raise the bar on customer trust as to satisfy it. Personalised health insurance premiums based on tracking how much people exercise or make other positive lifestyle changes are a case in point.

However, organisations that have already won a reputation for integrity can stake out a differentiating position by embracing such models and seizing opportunities that are too risky for less trusted brands. The most successful examples of this approach typically involve enterprises that follow the rule of reciprocity and give customers something they truly value as a quid pro quo for the data they share. These organisations also take great pains to use the data transparently and responsibly.

Conclusion

Like it or not, we’re entering an era in which our very lives are shaped by ones and zeroes. We all have a stake in this new world and a role to play in determining whether data becomes a force for evil or for good. If we get it wrong, we risk trapping ourselves in a “matrix” of our own making, a dystopian future in which predatory institutions harvest our data, algorithms dictate our choices and a few profit at the expense of the many. If we get it right – if public and private enterprises alike use our data in a trustworthy fashion and warrant the faith we repose in them – we could enjoy a better, richer existence than humanity has ever experienced before.

[1] Global Citizens & Data Privacy. Ipsos-World Economic Forum. 2019.

[2] “Build Your Trust Advantage: Leadership in the era of data and AI everywhere”. IBM Institute for Business Value. November 2019. ibm.co/c-suite-study. All subsequent references to the report come from this source.

[3] Ellett, John. “B2B Buyers Don’t Trust Vendors—And That Is A Huge Opportunity for Marketers.” Forbes. October 10, 2018.

[4] Martine, Kelly D., Abhishek Borah, and Robert W. Palmatier. “Research: A Strong Privacy Policy Can Save Your Company Millions.” Harvard Business Review. February 15, 2018.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of IBM.

About the Author

Ian Fletcher was educated in the UK, building a successful career in IBM Global Services. With more than 30 years’ experience in technology and business consulting services, Ian leads the IBM IBV C-suite Study research for MEA. He also runs IBM’s thought leadership programme, advising clients on business transformation and strategy. Ian specialises in the impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and, in turn, its impact on the C-suite and society.

About IBM

IBM is a leading cloud platform and AI solutions company. It is the largest technology and consulting employer in the world, with more than 380,000 employees, serving clients in 170 countries.

About IBM Institute for Business Value

The IBM Institute for Business Value, part of IBM Services, develops fact-based strategic insights for senior business executives.

IBM Global C-suite Study: ibm.co/c-suite-study

You may have an interest in also reading…

Small is Beautiful in Banking: Little US Institutions Form a Financial Backbone

Yerbol Orynbayev, former Deputy Prime Minister of Kazakhstan and World Bank governor, reports for CFI.co on the American banking sector.

The AI Economy Demands Leadership: Why Every C-Suite Needs a Chief AI Officer

By 2025, 35% of large organizations will have a Chief AI Officer (CAIO) reporting directly to the CEO or COO

Ian Fletcher, IBM: The Moral, Ethical & Societal Implications in a Smart-Human World

Every so often during our professional lives, something truly inspiring comes along, something that encourages us to look at the