OECD: 21st Century Trade Agreements & Regulatory Coherence

By Hildegunn Kyvik Nordås

In the past, services markets were largely local and countries mostly worked out their regulation without consideration for how other countries regulate. As a result, an abundance of different regulatory measures and systems exist across countries and sectors.

Technology and the cost and convenience of travel have brought most services onto international markets. With this development, the plethora of regulatory approaches and systems that is in place to solve the same problems has become an important constraint the effective and efficient international operations on firms.

To reduce the cost of international operations, regulatory cooperation in various shapes and forms has taken centre stage in trade and investment negotiations. Such agreements can substantially reduce trade costs and stimulate trade in services. However, regulatory harmonisation brings by far the largest gains when the harmonizing countries are relatively open to foreign trade and investment. Where significant barriers to services trade still exist, bringing them down is a prerequisite for regulatory cooperation to make a substantial difference for businesses.

Regulatory Cooperation

Mutual recognition, compliance assessments, and regulatory cooperation in specific areas feature prominently in recent trade and investment agreements. The objective of such regulatory cooperation is to simplify the life of companies, particularly SMEs, without compromising consumer protection or the independence of regulators. Systematic monitoring of implementation is however scant and assessments of the benefits of more coherent regulation far between, largely due to lack of adequate analytical tools.

Recent OECD work provides a new tool and demonstrates how it can be used for monitoring regulatory convergence and assessing its economic benefits. Based on the rich and detailed information in the Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) database, regulatory heterogeneity indices are created for each country pair and each sector. The heterogeneity indices exhibit the weighted share of policy measures for which countries have different regulation by country pair and sector. They take values between zero and one, where zero signifies country pairs that have exactly the same regulations in a sector, while one portrays country pairs that have completely different regulations.

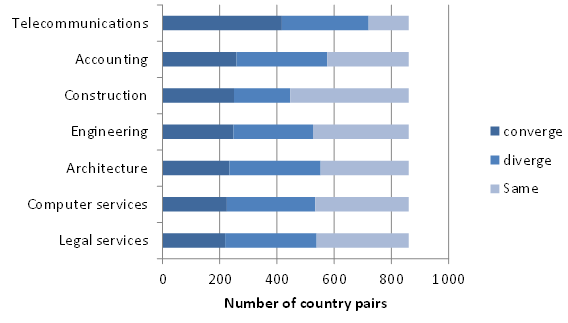

Figure 1: Changes in regulatory heterogeneity 2014-2015. Note: There are 861 unique country pairs in the STRI database. In total for the seven sectors, 31% of the country pairs converge, 34% diverge and 35% stay the same.

On average the country pair that has the most similar regulations is Norway and Sweden, where only 13% of the policy measures are different, while the least similar country pair is the US and India where almost half the policy measures are different. The average across all country pairs and sectors is about a quarter. There are also large differences across sectors as far as regulatory heterogeneity is concerned.

Legal services, broadcasting, and maritime transport have the most heterogeneous regulation. These are sectors that are subject to sector-specific national regulation and legal services and broadcasting are also among the sectors the least open to trade and investment. The lowest average heterogeneity indices are found in road transport and distribution services, two sectors that also have low average STRI indices. Note, however, that a high level of restrictions does not necessarily go together with heterogeneous regulation. Air transport, for instance, is a highly restricted sector, but where countries tend to restrict trade and investment in the same way.

Regulatory Convergence for Telecommunications

Figure 1 summarises the changes in regulatory heterogeneity from 2014 to 2015 for the seven sectors where information for both years is currently available. Two years is too short to establish trends, but the chart shows that with the exception of telecommunications a larger number of country pairs have become less rather than more similar.

Interestingly, telecommunications is one of the few sectors for which international trade agreements tend to have binding commitments related to behind the border pro-competitive regulation. Furthermore, international regulatory cooperation has been institutionalised for more than a century through the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

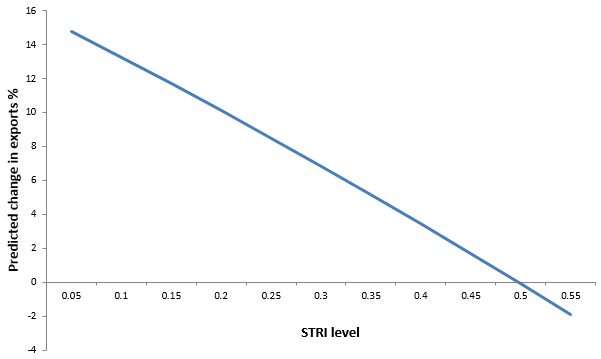

Figure 2: Predicted impact on services exports of reducing the bilateral heterogeneity index by 0.05 points. (When the country pair has the same level of restrictiveness)

Regulatory heterogeneity inhibits bilateral services trade flows, particularly in relatively open economies. As depicted in Figure 2, the trade stimulating effect of regulatory convergence is higher the lower the level of the STRI. For example, if two countries have the same low STRI score (0.1), harmonising regulation on a few measures is associated with about 12% more bilateral services trade.

In contrast, harmonising a few measures at an STRI level of 0.4 is associated with only 3.5% more bilateral trade. Intuitively, this means that harmonising regulations that constitute a significant barrier to trade and investment does not stimulate trade much. In fact, when the level of restrictiveness as measured by the STRI reaches a critical point around 0.5, harmonisation discourages trade.

Similar Levels of Restrictiveness

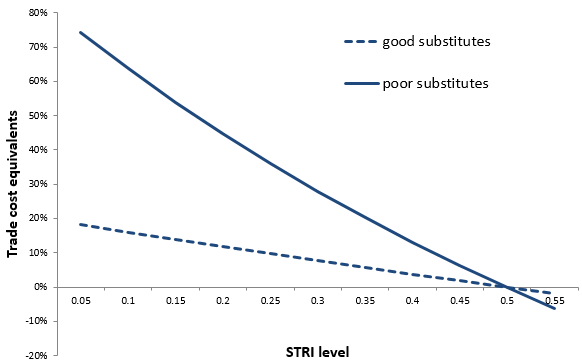

Regulatory convergence can reduce bilateral trade costs substantially. The trade enhancing effect of regulatory convergence depicted in Figure 2 is explained by lower trade costs due to the elimination of the duplication of compliance cost with regulation. Figure 3 exhibits the bilateral ad valorem trade cost equivalent of the average regulatory heterogeneity index (0.26) at different levels of restrictiveness. It shows that the trade costs implied by regulatory heterogeneity depend on the level of trade restricting regulation as well as how good substitutes local and foreign services are. The more similar the services, the better substitutes they are, and the less concerned are customers about where the service comes from.

Figure 3: The ad valorem trade costs of regulatory heterogeneity. (When country pairs have the same STRI score and the same regulation on a quarter of the measures) Note: The graphs in Figures 2 and 3 are calculated for cases when exporter and importer STRI levels are the same, depicted on the horizontal axis. The estimates take into account the interaction between the STRI level and regulatory heterogeneity.

Conversely, when services firms are highly specialized, for instance in engineering, architecture or legal services, customers care a lot about buying from the suppliers that best meet their needs. It is the latter type of services that will gain the most from regulatory cooperation. When markets are relatively open, trade costs imposed by regulatory differences range between 20% when local alternatives can be easily found and 75% when they cannot.

The results do not imply that overall trade costs are higher when the STRI scores are low, which a casual reading may suggest. Rather, when the STRI score is high, the level of restrictiveness dominates regulatory differences. For example, differences in qualification requirements and licensing procedures only matter if foreign suppliers can obtain a license to operate at non-prohibitive costs in the first place. Only then will they consider entering the market and face the cost of complying with a different set of regulations.

Policy Implications

As noted, regulatory cooperation has become prominent in trade and investment agreement, including the so-called mega-regional trade deals. It has been shown that such cooperation can potentially bring down the costs of servicing multiple foreign markets substantially. The trade stimulating effect is however larger the more open the cooperating partners are to trade and investment and the more specialized are the services. The policy implications that can be drawn from these findings are summarised in the bullet points:

- First, bringing down high levels of services trade restrictions or implement reforms to that effect unilaterally should be a first step. An STRI score above 0.4 in a sector is an indication that reforms should be a priority.

- At the same time, introducing forward-looking regulatory cooperation would avoid creating new sources of regulatory heterogeneity.

- As the level of trade restricting regulations comes down, more priority to regulatory cooperation should be given, both on future regulation and exploring ways to make existing regulation more coherent.

- Priority could be given to sectors with a high degree of specialisation, which also tend to be subject to sector-specific regulation.

- Make sure that regulatory cooperation successfully eliminates duplication of regulatory compliance costs for exporters in the areas covered by the agreement.

Finally, it appears that regulatory coherence is most successful when there are clearly defined regulatory objectives and well-proven regulatory tools are available, such as in telecommunications. A coordinating body also helps.

About the Author

Hildegunn Kyvik Nordås is a senior trade policy analyst at the Trade and Agriculture Directorate at the OECD, where she leads work on trade in services. This work has resulted in a number of OECD publications, workshops and presentations. Before joining the OECD in 2005 Nordås worked as a senior research fellow and research director at Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) in Norway where she did research on trade and development, policy analysis, and policy advice to governments and aid agencies. In addition she held a part time position as associate professor at the Department of Economics, University of Bergen where she taught international trade, macroeconomics and development economics at the master level. Work experience also includes two years as a counsellor at the research department in the World Trade Organization. She has been a visiting scholar to Stanford University, USA, University of Durban Westville, South Africa, and University of Western Cape, South Africa. She has published extensively in journals and books.

Hildegunn Kyvik Nordås is a senior trade policy analyst at the Trade and Agriculture Directorate at the OECD, where she leads work on trade in services. This work has resulted in a number of OECD publications, workshops and presentations. Before joining the OECD in 2005 Nordås worked as a senior research fellow and research director at Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) in Norway where she did research on trade and development, policy analysis, and policy advice to governments and aid agencies. In addition she held a part time position as associate professor at the Department of Economics, University of Bergen where she taught international trade, macroeconomics and development economics at the master level. Work experience also includes two years as a counsellor at the research department in the World Trade Organization. She has been a visiting scholar to Stanford University, USA, University of Durban Westville, South Africa, and University of Western Cape, South Africa. She has published extensively in journals and books.

You may have an interest in also reading…

2012 CFI Top 100 Emerging Markets Companies’ Nominations

The 2011 CFI Top 100 Emerging Market Companies were compiled by using the nominations and the votes from CFI’s subscriber

The Euro Crisis Should Distract on Rio+20 Agreement

Much of the world’s attention has been focused on the Euro crisis but this should not be allowed to distract

Government of India and World Bank Sign $500 Million Agreement to Improve Access to Finance for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises

The Government of India and the World Bank today signed a $500 million loan agreement for the MSME Growth Innovation