UNCDF: Bringing New Parties to the Table – Engaging the Private Sector to Drive Investment into Least Developed Countries

Author: Esther Pan Sloane

It is widely understood that the world is falling far short of the funding flows required to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly in the world’s 47 poorest countries, known as Least Developed Countries. The financing gap is estimated at $2.5 trillion. A key part of this gap is foreign direct investment (FDI). FDI is important for developing countries where it is the largest and most consistent external source of financing, ahead of portfolio investments, remittances, and official development assistance (ODA). But, for LDCs foreign direct investment is essential. They also remain highly dependent on ODA and are vulnerable to external factors, including exchange rate fluctuations and weak commodity prices.

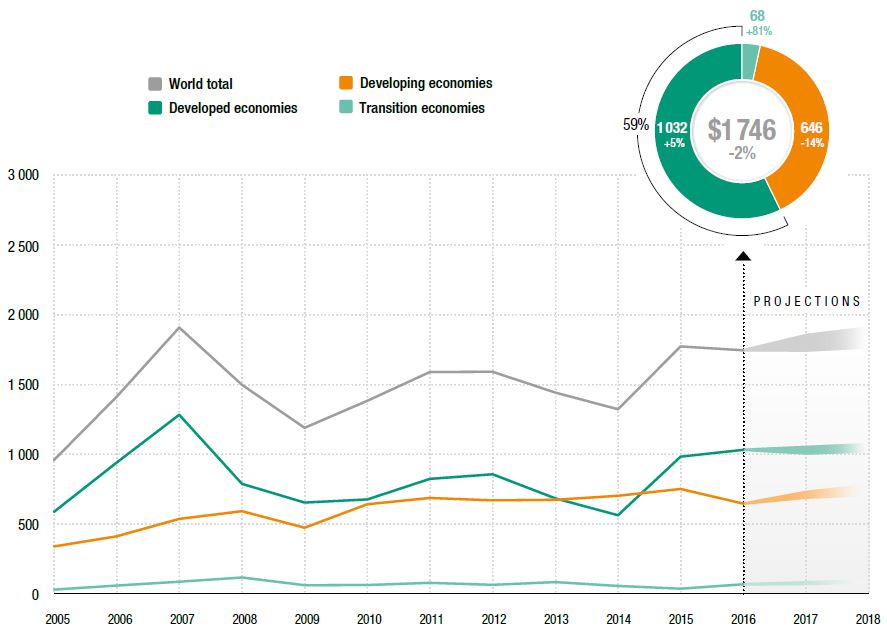

Overall, the trends for FDI to the poorest countries are not positive. In 2016, FDI flows to the least developed countries fell by 13% to $38 billion. Flows to small island developing states were only $3.5 billion (a decline of 6%), while landlocked developing countries saw FDI stay stable at $24 billion. For developing economies overall, FDI declined 14% to $646 billion. This amount was not divided equally: of the 79 developing economies in the African, Caribbean, and Pacific group of states, the top ten recipients accounted for 65% of FDI inward stock in 2016, with the Pacific subgroup receiving the smallest share of inflows.

“The challenge is clear: how can we direct more of the estimated $78 trillion held in portfolio and other investments worldwide to the poorest countries to support their sustainable development?”

Some studies on the effect of capital inflows on domestic investment in developing countries from 1978-1995 show that increases in capital inflows were associated with a corresponding increase in domestic investment. The United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) found that its involvement in co-financing deals in LDCs with grants or loans, as well as support provided through technical assistance, is a key factor in convincing domestic banks to invest in deals in their country’s poorest and most remote regions.

Other studies have found that FDI allows technology transfer, training, and capacity building of local employees, and increased corporate tax revenues in host countries.

According to UNCTAD, global FDI flows are expected to increase by about 5% in 2017 to almost $1.8 trillion, and reach $1.85 trillion in 2018 – still below the 2007 peak. Karl Savant, resident senior fellow at the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment of Columbia University, estimates that FDI flows need to reach a level of four or five trillion USD annually in order to meet the investment needs of the future.

Figure 1: FDI inflows, global and by group of economies, 2005-2016, and projections, 2017-2018. (Billions of dollars and per cent).

Source: © UNCTAD, FDI/MNE database (www.unctad.org/fdistatistics).

The challenge is clear: how can we direct more of the estimated $78 trillion held in portfolio and other investments worldwide to the poorest countries to support their sustainable development? Peter O’Driscoll, a partner at Orrick, Herrington, and Sutcliffe and head of the Emerging Markets Group, wrote in ImpactAlpha on June 2017 that a new model for driving impact-driven growth capital equity investment in the world’s poorest countries could be a large private fund, of between $600 million and $1 billion, run by a manager focused on growth capital equity across the 23 poorest countries in the world. Growth capital equity to support small and medium enterprises, early stage companies and start-ups must complement the existing investments by development finance institutions in areas such as microfinance. Mr O’Driscoll points out that there are currently only five local private equity funds across the 23 poorest countries – two in Afghanistan and one each in Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Ethiopia.

Creating viable private investment vehicles to direct more foreign direct investment to LDCs would have a significant and lasting impact on the sustainable development of those countries.

Many impact investors raise three issues as particular barriers to investing in LDCs: unfriendly regulatory environments, complex regulations, and a perception of political and financial risk.

Agenda 2030 and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda both stress the importance of creating the right “enabling environment” for investment and the growth of the private sector. This includes rule of law, enforcement of contracts, and a commitment to fighting corruption. Mr Sauvant argues for a concerted international effort to help developing countries, particularly LDCs, improve their FDI regulatory frameworks and investment promotion capacities through an International Aid for Investment Initiative or a Sustainable Investment Facilitation Understanding.

These efforts could help developing countries define “sustainable foreign direct investment for sustainable development” – that is, viable commercial investments that make a contribution to the economic, social, and environmental development of the host country. Other impact investors have also called for reform of the international investment law and policy regime, particularly in LDCs, to standardise central bank approaches to investment regulations and create a supportive environment for investors.

UNCDF’s own experience with regulations around digital finance – convening governments and private sector stakeholders to identify blockages to the expansion of digital financial inclusion, then helping the government to pass regulations easing those barriers – can have a significant impact on the willingness of private sector actors to move into certain industries in LDCs.

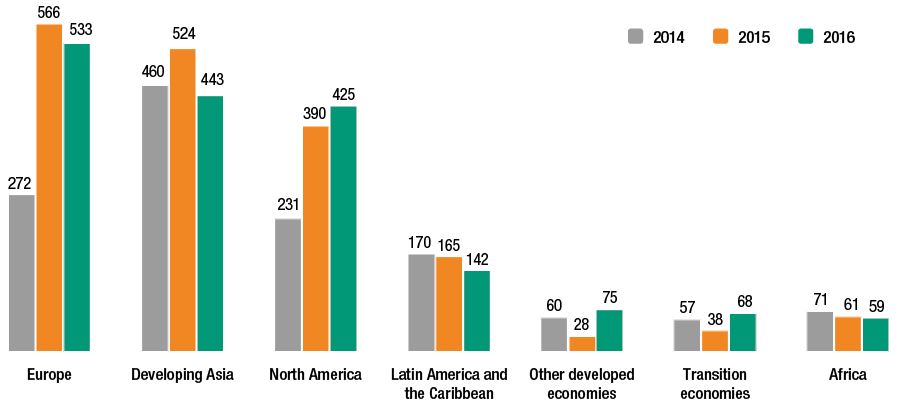

Figure 2: FDI inows by region, 2014–2016 (Billions of dollars). Source: © UNCTAD, FDI/MNE database (www.unctad.org/fdistatistics).

There is also growing support across the UN system for LDCs to access the legal and other expertise they need. The International Development Law Organization and the UN Office of the High Representative for Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries, and Small Island Developing States have created a programme to support investment to LDCs. The Investment Support Programme for the LDCs was launched in September 2016 and provides on-demand legal and professional assistance to both LDC governments and under-resourced private sector firms in LDCs to help support them in investment-related negotiations and dispute settlement. The programme’s objective is to establish an international scheme for legal aid and expert assistance.

Measures like this will help build the capacity of both governments and private sector companies to develop the expertise they need to manage sophisticated investment regimes in the future.

UNCDF also has a long history of “de-risking” both public and private sector investments by using ODA funding to catalyse other resources, public and private, mainly from domestic banks. As Anders Berlin wrote in this magazine’s Autumn 2017 issue, UNCDF is currently creating an investment fund for LDCs to blend public and private sources of funding and invest them through loans and guarantees into promising investments in LDCs. This fund will direct more private debt and portfolio equity – what Mr O’Driscoll identified as what is most needed – to LDCs, whilst also targeting smaller transaction sizes and higher risk tolerances than most active investors are currently considering. The hope is to continue UNCDF’s tradition of demonstrating a viable market, proving the success of the concept, and then crowding-in additional financing. If this and the other ambitious models discussed above work, they will help to achieve the shared goal of supporting the LDCs to grow, prosper, and achieve their sustainable development goals.

About the Author

Esther Pan Sloane, a U.S. national, joined UNCDF as the Head of the Partnerships, Policy and Communications in October 2016.

Prior to joining UNCDF, Esther was a U.S. diplomat for 10 years. As Adviser at the Permanent Mission of the United States to the United Nations in New York, she was on the U.S. team that negotiated the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals. She also served on the Executive Boards of UNDP, UNICEF, UNOPS, and UNFPA, pushing the agencies to become more efficient, effective, and accountable for results.

Esther previously served as a U.S. diplomat in China and the United Kingdom, as well as at the State Department Operations Center in Washington.

Prior to joining the U.S. Foreign Service, Esther worked as a journalist in print, radio, and magazines. Esther graduated from Stanford University with a BA with honors in English and International Relations and earned an MA in Theater and Performance from the University of Cape Town, which she attended on a Fulbright Fellowship.

You may have an interest in also reading…

The Renewable Electricity Grid: The Future Is Now

New World Bank report finds that with the right policies and investments, countries can integrate high levels of variable renewable

WEF India Summit: Finally, Something Worth Watching

There are downsides to arranging a panel at a conference like the World Economic Forum’s India Economic Summit with broadcast

G8: Could the Solution to Growth be Simpler Taxes?

There has been much talk of the need for growth at the G8 meeting. Could it be that the solution