World Bank Group: Financial Inclusion – Banking on Low-Income Households

Author: Douglas Pearce

Financial exclusion restricts economic opportunity and constrains poverty reduction. Yet today there are an estimated 2.5 billion adult people worldwide who go about their lives without any formal financial services such as bank accounts. According to the World Bank’s Global Findex Survey, almost 80 percent of those living on incomes of less than $2 per day are financially excluded. Low-income households and women are disproportionately affected, which further holds back poverty reduction and ultimately limits economic growth.

The aspiration of universal financial inclusion is increasingly prominent on the global economic agenda in recognition of its importance. More than fifty countries have set national targets to expand financial inclusion. Innovative models to extend financial access have generated a buzz around transformational business models. Examples of these models include China’s Alibaba which focuses on SME finance and is based on ‘big data’ and supply-chain relationships; and, M-Pesa and Equity Bank in Kenya. The former processes payments through mobile phones while the latter welcomes low-income clients through alternative delivery mechanisms.

Financial inclusion provided two of the proposed indicators in the UN High Level Panel’s report for post-2015 development goals.

World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim has laid down a marker in terms of vision, stating that universal financial access should be achievable by 2020. At the World Bank-IMF Annual Meetings this year, he made the case that “universal access to financial services is within reach – thanks to new technologies, the use of ‘big data’ transformative business models and ambitious reforms.” He noted that “as early as 2020, such instruments as mobile wallets and other e-money accounts, along with debit cards and low-cost regular bank accounts can significantly increase financial access for those who are now excluded.”

Payments as a First Point of Access

The initial point of entry to financial access for many low-income households is the receipt of wages, benefits or remittances as an electronic payment credited to a card (which may or may not be linked to a bank account), mobile wallet or any other form of e-money account, or to a regular bank account.

“Innovative models to extend financial access have generated a buzz around transformational business models.”

The growth of electronic payment products – which can be used through the expanding networks of relatively low-cost access points such as ATMs, point of sale terminals, non-bank correspondent agents and mobile phones – is therefore significantly expanding financial access. World Bank data show that these transaction instruments are generally growing faster than deposit accounts at commercial banks. In those countries home to the vast majority of the unbanked, payment cards are growing every year at more than twice the rate as regular bank accounts do.

Bank Accounts as a Gateway to Financial Inclusion

The ultimate goal is to achieve full financial inclusion – in other words, the ability of all adults and firms to access and use a range of financial products and services that fits their particular needs. To achieve financial inclusion, improving access to financial services is only the first step.

An important next step toward financial inclusion is a savings or checking account at a regulated financial institution, such as a bank or credit union. This can open up access to savings (which evidence shows is directly linked to poverty reduction), credit, and insurance (to buffer the poor against the risks of sickness and catastrophic events) – thus reaching far beyond transactions and payments processing only.

The commitments to ambitious reforms made by more than fifty countries to expand financial inclusion can accelerate the expansion of access to such regulated accounts. Barriers that limit the power of investment, technology and innovation to reach the unbanked with financial services can thus be dismantled.

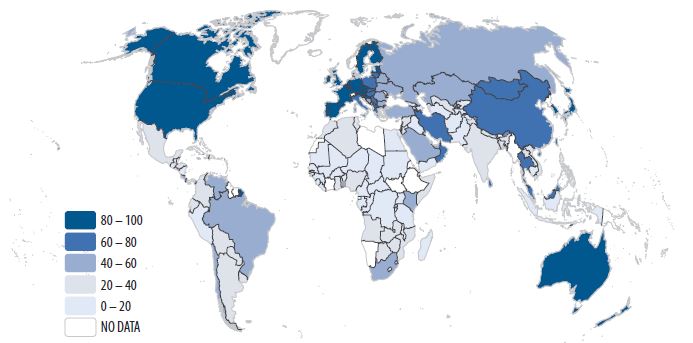

Map 1: Adults with an Account at a Formal Financial Institution. Source: Global Financial Inclusion Database, World Bank.

Government actions – such as shifting government-to-person (G2P) payments from cash to electronic methods and depositing these payments directly into accounts – can help kick start the design and rollout of new business models and products. For example, India is in the process of building an entire platform for payments around its new biometric-based national identity program. This promises to offer huge cost savings and allows for shifting payments to electronic transfers directly into accounts.

Bank accounts with lower entry requirements, fewer fees and a streamlined product offering can enable many more low-income individuals to open and benefit from regulated deposits, as well as payments and transaction services, and potentially also credit and insurance. Countries such as Brazil, South Africa and the United Kingdom have introduced such accounts in order to open up access to the unbanked. Many other countries are now following suit.

The Economics of Accounts for Low-Income Consumers

Data is increasingly available to assess the business case for serving low-income households and microenterprises, and to develop accounts and other financial products for that un-served, or under-served, demographic. This includes information on price and fee sensitivity, available cash flows, and the relative viability of delivery models. Such data has been developed by the World Bank, the World Savings Bank Institute (WSBI), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and others.

The WSBI’s Doubling Savings Accounts Programme, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, has supported low-income account pilots through savings and postal banks in ten countries since 2009. The findings from these ongoing pilots offer valuable insights into the economics of low-income bank accounts. The pilots have demonstrated that making the products work for banks may be as important as designing products that appeal to the unbanked and low-income target groups[1]. The three main lessons learned are:

- Traditional bank branches will not reach the majority of the unbanked, and alternative financial service access points are needed. While a full branch needs a minimum market size of 9,000 clients, the minimum viable number of clients for an agent (such as a retail store) is only 700, while for an ATM kiosk it is 2,000. For a mini branch the figure is 4,000[2]. In some countries like Tanzania or Indonesia, locations that can support a full branch or a bank agency would only reach a quarter of the whole population. Banks therefore need to partner with outlets that can extend their reach, such as mobile money operators.

- Simplified or basic bank accounts with clear and affordable pricing can spur adoption. Simplified product design, proportional know-your-customer requirements and clear marketing messages can all induce greater client take-up. Banks should also look to price their services at a level that is affordable in order to develop a future customer base. In the ten pilot countries studied, the amounts that customers spend on fees can equal a full day’s cost of living. Banks should therefore target about 60 cents per month in least-developed countries and a dollar a month in middle-income countries, for customers to conduct two or three transactions per month.[3]

- Services provided should be sustainable for the bank. WSBI argues that sustainability should be possible, although challenging, even at the sub-$25 monthly balance level typical of the poor. The key is to charge a monthly fee that can be paid out of the household budget, and to provide service at sufficient scale in order to cover overhead. A significant increase in the customer base is therefore critical to success.[4]

What Is Needed to Bring the Private Sector Fully on Board?

If banks and other financial institutions see financial inclusion reforms and other public-sector actions as out of step with their market realities – or if they view targets and strategies as a top-down imposition to be avoided or managed – then the potential impact of these actions will be watered down. Serving low-income households profitably is challenging, as the WSBI pilots illustrate.

Well-intended initiatives by policymakers often fall short of achieving their potentially transformational impact. For example, introducing basic – i.e. simplified and accessible – bank accounts, or opening new accounts for recipients of benefits, has in many cases not yet had the intended boost to financial inclusion. Many of those accounts remain under-used. Only about one in five (22 percent) of accounts in low- and middle-income countries are used frequently (more than three times a month for withdrawals), compared to 72 percent of accounts in high-income countries, according to the Global Findex Survey.

To address this challenge of dormancy or under-use of accounts, account-related costs need to be made affordable, financial awareness levels may need to increase, and access to accounts needs to be made as convenient as possible, as the WSBI pilots also indicate. Low levels of usage and limited uptake by consumers can be linked to financial institutions often not viewing new, lower-income consumers as an attractive business proposition, and therefore not developing sufficiently attractive and tailored products for them. Low uptake may also be due to account-design parameters being too strict and inflexible, if regulators have intervened to set or control those parameters.

Financial-service providers such as banks, credit unions and (where permitted) telecom companies therefore need to be engaged in informing and taking shared ownership of financial inclusion targets and strategic priorities. The momentum in many emerging markets to quickly draft and launch financial inclusion strategies with top-down targets may need to be adjusted, and processes may even need to be re-started, if the prize for doing so is private sector buy-in and a better likelihood that targets will be achieved and surpassed.

Achieving the right balance between the private sector participation in setting financial inclusion targets and prioritizing reform measures – while ensuring that financial-service providers truly rethink business models and financial products to fit low-income households and microenterprises – will be central to the achievement of the targets set. Similarly, regulators and policymakers need to balance financial inclusion targets with stability, competition, integrity and market-conduct priorities, to ensure that financial inclusion is fully beneficial to the economy, to the financial sector, and to low-income households.

About the Author

Douglas Pearce is the manager of the Financial Inclusion & Infrastructure Practice at the World Bank. He previously served at DFID, the United Kingdom’s development agency, as the leader of the financial sector team and deputy head of the Growth and Investment Group. Here he also chaired the Steering Committee of the Financial Reform and Strengthening Initiative (FIRST). Prior to that, Mr Pearce served as a senior financial sector specialist at the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), and set up and managed a microfinance institution, among other roles. Sarah Fathallah and Christopher Colford, both of the World Bank, contributed to this article.

References:

[1] WSBI Note: 18 Months after the launch of the “Doubling savings accounts” project: What lessons have we learned? March 2011.

[2] WSBI Working Paper: Mapping proximity – Bringing products and services close enough to the poor to be meaningfully usable and still keep them sustainable for WSBI partner banks. April 2013.

[3] WSBI Presentation: WSBI programme to double savings accounts at members. June 2013.

[4] WSBI Note: What makes pro-poor service delivery sustainable for WSBI partner banks? August 2012.

You may have an interest in also reading…

Corruption as the Scourge of Development: The Case of Venezuela

Corruption is the scourge of development. From outright stealing and cooking the books to kickbacks and price-fixing; corruption permeates some

IFC: Addressing Climate Change Can Unlock $23 Trillion-Dollar Investment Opportunities in Emerging Markets

By Christian Grossmann and Thomas Kerr The historic Paris climate change agreement entered into force in record speed last November,

IFC Champions Water Efficiency in China’s Textile Industry

China’s vast textile industry is a boon to the country’s economy, but consumes high volumes of water. This is a