NEPAD: Towards the AU Agenda 2063 – Africa Building Momentum From a Decade of Achievement

At the dawn of the 21st century, African leaders were faced with a set of new realities: Globalization, the end of the Cold War, and lessons from the challenges and experiences of the Organization of African Unity (OAU). These are arguably most likely to have added to the momentum that led to the formation of the African Union (AU), with its promise of greater integration, peace and prosperity.

At the dawn of the 21st century, African leaders were faced with a set of new realities: Globalization, the end of the Cold War, and lessons from the challenges and experiences of the Organization of African Unity (OAU). These are arguably most likely to have added to the momentum that led to the formation of the African Union (AU), with its promise of greater integration, peace and prosperity.

This year marks the 50 year celebration of the establishment of the OAU. In this article, we attempt to identify some of the features that make the continent a better place today and describe the challenges that lie ahead for the AU as it crafts its recently announced Agenda 2063, intended to benefit African people as a whole over the next half century.

The New Pan-African Institutions

The transformation of the OAU into the AU marked a sea change in the nature and character of continental institutions. The AU established a peace and security architecture that had the specific intention of intervening in conflicts with a view to resolving them. It is also meant to be an innovative instrument of promoting and sharing good practices on governance through the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM). The other goals identified early on focused on eradicating poverty, facilitating economic growth and development, and ensuring that Africa is well represented internationally in support of the continent’s objectives.

“The continent is making important strides on conflict resolution and governance issues.”

The adoption of the New Partnership for African Development (NEPAD) as the socio-economic blueprint for the continent was also a decision with far-reaching implications. The NEPAD programme is premised on Africans leading their development processes (politically and technically), promotion of regional integration, gender equality and developing the capacities of African peoples to participate in their own development processes, including those in the diaspora.

The Rising Continent

It can be argued that over the last decade – through the AU and its NEPAD program – African leaders have contributed towards the creation of an environment conducive to development on the continent.

As pointed out in the Africa Progress Report 2012, drawn-up by the Kofi Annan Panel, the continent is making important strides on conflict resolution and governance issues. Multiparty elections are now firmly established; there have been moves towards greater transparency; and armies have, by and large, stayed out of politics. Many countries have also become more peaceful.

Such successes have also been replicated on the socio-economic front. From 2000 onward, levels of annual economic growth in Africa have been impressive, averaging some 5% until the onset of the global economic recession. The World Bank called this “the longest expansion in 50 years”. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) notes that in the nearly five years since the 2008 crisis, Africa has grown faster than in the years before the crisis. Regional output grew 5.1% last year and should remain high, though perhaps slightly weaker as reflected in the rather subdued World Economic Outlook released in July 2013.

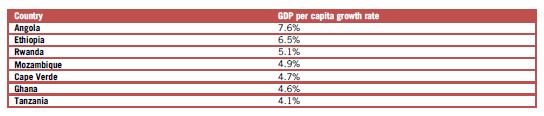

This recent experience of African countries is quite significant because it has not been limited to commodity rich countries. Economic growth in most countries now seems able to attain levels higher than population growth (see table below).

There is also evidence of a few structural changes that are taking place more rapidly since the turn of the century. These bode well for the future and include the declining share of agricultural in GDP (some places recorded a drop from 40% to 15%) and the increased contribution of industry.

Africa’s progress over the last thirteen years is also illustrated by its endeavours to meet the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs). For example, a recent report with contributions from both the AU and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) notes that Africa is on track to achieve the targets of universal primary education; gender parity at all levels of education; lower HIV/AIDS prevalence among 15-24 year olds; increased proportion of the population with access to antiretroviral drugs; and increased proportion of seats held by women in national parliament by 2015.

The 2012 report further notes that in some cases Africa’s achievements exceed those of regions such as Southeast Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean.

Many of these successes can be attributed to Africans themselves. Levels of debt have been reduced, government spending supportive of growth has increased. This has significantly enhanced the attractiveness of African economies to domestic and international investors.

As a result of lower debt levels, African countries are now better able to adopt far-reaching policies for their sustained development, including investment in infrastructure and human capital. This is taking place despite a dramatic fall in the volume of development aid received.

Table 1: Leading African performers 2002-2012- GDP per capita. Source: based on Chandy et al, Brookings Institution, 2013.

The role of the African private sector in this success story cannot be understated. The Ernst & Young Africa Attractiveness Survey (2012) found that intra-African investment in new projects increased by an average of 23% every single year between 2003 and 2011. Since 2007 this rate has accelerated to an average of 42% a year. The report further indicates that this trend is being led by Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. Over the last four years, investments from Kenya and Nigeria are reported to have grown at higher rate than is recorded anywhere else in the world, at 77.8% and 73.2% respectively.

Challenges Ahead

Africa’s recent success is reflected in its ability to achieve and maintain peace and security across the continent although pockets of conflict remain. By all accounts measures to address these realities are in place but problems remain.

Africa’s economies are also growing though it is acknowledged that the gains are often neither inclusive nor shared. Various analysts have noted that the aggregate performance of African economies hides significant diversity across and within countries. Growth often fails to reduce poverty levels. In other parts of the world, growth has impacted societies in a much more equitable way (see for example World Bank’s Africa’s Pulse, April 2013).

Inequality also remains high. Over the next twenty years, African poverty is expected to drop by a substantial 24 percent but its share of global poverty may rise to 82 percent. In its short-term forecast, the International Labour Organization (ILO) also expects the number of unemployed people in Sub-Saharan Africa to rise by 5.4% and by 4.3% in North Africa by 2015. The outlook for youth unemployment doesn’t look any more promising.

Africa’s socio-economic challenges are clear. However, better growth prospects and the availability of resources will enable African countries to achieve even more success and meet MDGs in areas such as under-5 mortality, maternal health and undernourishment.

Africa’s Road Ahead

As correctly observed by many, including analysis at the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), African governments and peoples have been the main players in this new era of progress.

The continent now has in place the requisite institutions for addressing its problems and to sustain the current positive trends. It may also be able to widen the benefits of the opportunities that it faces, especially as an emerging growth pole of the global economy with more than a billion people depending on its fortunes.

These changing fortunes emerged when Africa took its destiny in its own hands. Such an approach should inform its relations with the emerging BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India and China) and older centers of global economic power, such as the United States and Europe.

Without a doubt the success of the last decade must lead to increased African self-confidence. It also must ensure that the processes it has initiated to develop long-range strategies for development, re-affirm the importance of the following guiding principles:

• People-centred development

• Promotion of democratic values and standards

• African ownership and leadership of processes for its own development.

This approach may imply less acceptance of the need for a ‘paradigm shift’ as this undermines the progress that Africa has made over the past decade on its own.

Similarly, the emphasis on ‘governance’ should not make Africa feel that institutional weaknesses cannot be overcome as was seen in countries that experienced long spells of growth and managed to lift millions out of poverty (e.g. East Asia early 1960’s, China and Vietnam circa 1980).

Africa will need to continue to emphasise the role of a capable and people-focused state. Its ability to develop partnerships with broader civil society, including the private sector, will continue to be crucial, as will be the conscious efforts to import, modify and rapidly invent the institutions vital for dynamic industrialization and structural transformation.

Mkandawire (2001) makes the important point that we wish to underline. The real issue is no so much the “building” of the African state but rather “making it a more accountable and more efficient instrument for addressing the issues that African’s have reason to consider fundamental”.

Civil society, particularly business, must also become a more significant part of efforts towards domestic resource mobilization.

It is encouraging to see the growth of intra-African investment, as earlier mentioned, but there is scope for improvement in harnessing domestic financial resources and narrowing resource gaps through better functioning financial markets. This will further reduce reliance on foreign aid and allow local ownership of development processes.

Conclusion

Projections for the next half century suggest that Africa can realize a vision of a united, prosperous continent at peace with itself and boasting well diversified, competitive economies from which extreme poverty and inequality have been eliminated.

Africa is a continent that has many opportunities: Land and mineral wealth abound and an eager youthful and growing population. The prospects of urbanization and a changing global environment clearly favour emerging regions.

The AU and its NEPAD programmes represent a step taken. Now is time for careful planning to anticipate the new challenges and opportunities ahead and formulate an adequate response to them. It will be important that the development of the AU’s Agenda 2063 incorporates the values, principles and successes attained to date.

Mgidlana works for the Presidency and the Nepad Planning and Co-ordinating Agency but the views expressed are his own. Maziya is a research fellow at the agency.(This is the second article in a series exploring the evolution and focus of Pan-African institutions, challenges and prospects facing the continent and implications for the AU’s Agenda 2063).

About NEPAD

The New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) is a flagship socio-economic programme of the African Union (AU). NEPAD’s four primary objectives are to eradicate poverty, promote sustainable growth and development, integrate Africa in the world economy and accelerate the empowerment of women.

The NEPAD Agency is a technical body of the AU that advocates for NEPAD, facilitates and coordinates development of NEPAD continent-wide programmes and projects, mobilises resources and engages the global community, regional economic communities and member states in the implementation of these programmes and projects. The NEPAD Agency replaced the NEPAD Secretariat which had coordinated the implementation of NEPAD programmes and projects since 2001.

The strategic direction of the NEPAD Agency is premised on six themes: Agriculture and Food Security, Climate Change and Natural Resource Management, Regional Integration and Infrastructure, Human Development, Economic and Corporate Governance as well as Cross-Cutting Issues including Gender, ICT and Capacity Development.

You may have an interest in also reading…

From Germany to South Africa – The Oppenheimers: Diamonds Are Not Forever

“I’m a philistine.” Nicholas F Oppenheimer, worth some $6.5bn, is not likely to be spotted at a theatre or opera

Banco Société Générale Moçambique: Established, Respected, Clear on Priorities, and Transparent in All its Dealings

Mozambique institution has a major European player as a shareholder — and an A rating from S&P… With a presence

IFC on Climate Smart Investment: A Gateway for Green Growth in South Asia

Today in India, with a tap of a smartphone, a manufacturer instantly books shipping services for his/her goods through a