The Cost Curve That Is Squeezing Coal and Gas

By the end of 2025, the energy transition’s most persistent objection — that renewables cannot be relied upon when the sun sets and the wind drops — looked far less convincing. Not because politicians mandated a new outcome, but because the economics shifted underneath the grid.

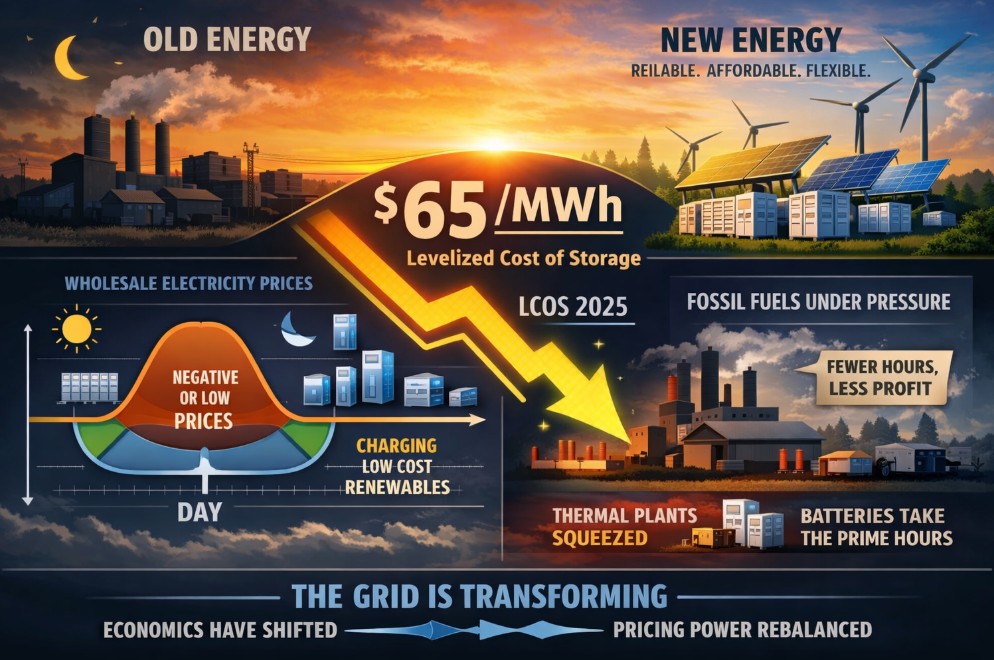

In October, the levelised cost of storage (LCOS) in major markets outside China and the United States fell to roughly $65/MWh, according to Ember’s December 2025 analysis. LCOS varies by duration, financing and local conditions, but the direction is clear: storage is becoming cheap enough to move large volumes of low-cost renewable electricity into peak hours. For fossil generators, the danger is not a single regulatory event. It is the slow, compounding collapse of their pricing power.

This is the point where the energy transition becomes less about subsidies and more about system maths. When the grid can shift cheap midday solar into the evening, “reliability” stops being a fossil advantage. It becomes a service that can be provided by the flexibility stack — batteries first, and then other long-duration options as they mature.

The $65/MWh Inflection

A $65/MWh LCOS milestone matters because it changes the profitability of time-shifting. In many markets, it becomes economically compelling to charge batteries when solar and wind push wholesale prices towards zero — or below — and discharge when demand peaks. The value is not only the average cost of energy; it is the shape of prices across the day and the ability to capture the right hours.

That shift increasingly compresses the revenue model of thermal plants. Gas and coal were not built to compete against near-zero marginal cost generation plus arbitrage. They were built to run for long stretches, recovering fixed costs through high utilisation. The more the grid favours renewables and storage, the more thermal plants are forced into a narrower role — fewer running hours, more starts and stops, and greater reliance on external support mechanisms.

Clean Power’s Cost Advantage Is Now Structural

The broader cost curve remains decisively in favour of renewables. In its latest assessment, IRENA reports that 91 percent of newly commissioned utility-scale renewables in 2024 produced electricity cheaper than the cheapest new fossil alternative, helping avoid $467bn in fossil fuel costs that year. Renewables are no longer “competitive”; they are increasingly the default choice for new capacity in most markets.

Storage is on a similarly steep decline. IRENA notes that fully installed battery storage project costs fell 93 percent between 2010 and 2024, from $2,571/kWh to $192/kWh, as outlined in its analysis of storage as a bridge between supply and demand gaps in renewable systems (IRENA). Meanwhile, BloombergNEF’s 2025 survey found average lithium-ion pack prices fell another 8 percent in 2025 to $108/kWh, with stationary storage packs reaching $70/kWh (BloombergNEF).

In the United States, the widening gap is evident in Lazard’s June 2025 LCOE+ work, summarised in Reuters coverage. New utility-scale solar costs are cited in a range of roughly $38–$78/MWh, while new gas combined-cycle plants are placed at roughly $48–$109/MWh. The overlap is not the point; the trajectory is. Renewables are improving with scale and learning curves. New gas is being pulled upwards by higher capital costs and increasingly complex risk premia.

The Negative-Price Trap

Energy debates often fixate on average costs. The more decisive battleground is hourly pricing — who captures value when prices are high, and who is forced to operate when prices are low.

Wind and solar have near-zero marginal costs. When abundant, they push wholesale prices down, increasingly to zero or negative levels. Thermal plants cannot live comfortably in that world because they still face fuel costs, variable maintenance, and physical constraints that make cycling expensive.

Batteries, by contrast, thrive on volatility. They charge when prices are low — sometimes being paid to absorb excess generation — and discharge into peaks. As storage costs fall, batteries become progressively more aggressive competitors for the very hours that historically subsidised gas.

This is where the structural squeeze intensifies. Gas plants have long relied on peak periods to earn a disproportionate share of their revenue. When batteries begin to dominate those peaks, gas loses the premium hours while still being exposed to low-priced hours. Run-times fall, revenues thin, and fixed costs must be recovered over fewer megawatt-hours. The unit economics deteriorate not because the plant “stops working”, but because the market stops rewarding its operating profile.

The result is an increasingly familiar pattern: thermal assets that remain physically useful but become economically fragile, surviving through capacity payments, reliability contracts, or other forms of external support. The grid may still require back-up capacity during rare stress events, but the old logic — that “always-on” automatically means “commercially viable” — is fading.

Daily Volatility Is Being Solved; Seasonal Volatility Is Not

Lithium-ion economics have made daily arbitrage increasingly straightforward: shifting solar from noon to evening is now routinely viable in leading markets. The harder problem is seasonal and multi-day variability.

The International Energy Agency has explored the challenge in its work on managing seasonal variability. In most markets, it is not economic to build enough lithium-ion capacity to cover a fortnight-long winter lull. That creates a distinct “insurance” market — one where different technologies, contracting structures and policy tools will matter more than day-to-day optimisation.

Hydrogen is often positioned as part of this strategic reserve. Its core attraction is scale: it can store large volumes over long periods. Its limitation is efficiency. Power-to-hydrogen-to-power routes are materially less efficient than batteries, making hydrogen more credible as a rarely used backstop than an everyday balancing tool. It is insurance: expensive, but valuable in the deepest gaps.

Between daily batteries and seasonal backstops, technologies are emerging to cover the “multi-day” middle. Form Energy’s iron-air systems, designed for multi-day discharge, are being deployed in the United States, including an 85MW project in Maine announced via the State of Maine’s programme update. Sodium-ion is also edging into utility conversations, with Peak Energy announcing a phased agreement with Jupiter Power covering up to 4.75GWh of supply, as detailed in Peak’s announcement and reported by pv magazine.

The picture is not a single winner, but a layered flexibility stack — short-duration batteries for the daily cycle, multi-day solutions for weather systems, and strategic backstops for rare seasonal extremes.

California’s Dispatch Stack Is Already Changing

California offers a real-world view of how this transition unfolds on a large, complex grid. In 2024, renewable resources — including hydro and small-scale solar — supplied 57 percent of California’s in-state electricity generation, according to the US Energy Information Administration’s state profile.

Momentum accelerated in 2025. In the first eight months, utility-scale solar generation reached 40.3bn kWh, nearly double the same period in 2020, while natural gas generation fell by about 18 percent versus the same period in 2020, according to an EIA Today in Energy analysis. The more telling change is the evening peak. Battery generation during peak evening hours rose from under 1GW in 2022 to an average of 4.9GW in May–June 2025, per the same EIA analysis. That is storage beginning to claim the grid’s most valuable hours.

Capital Is Following the Curve

Investment patterns are now reflecting the economics. The IEA projects global energy investment will reach $3.3tn in 2025, with $2.2tn directed to clean-energy technologies, as set out in its World Energy Investment 2025 report and summarised in Reuters coverage. Renewable investment data point in the same direction, with BloombergNEF reporting global investment in new renewable energy development of $386bn in H1 2025, up 10 percent year-on-year (BloombergNEF).

This is not simply an ethical reallocation. It is capital moving towards technologies with declining costs and expanding addressable markets — and away from assets facing a tightening economic corridor.

A Grid That Has Already Begun to Re-Optimise

Fossil generation will not vanish overnight. Gas, in particular, is likely to remain online in many markets as a backstop for stress events and longer-duration gaps that batteries cannot yet bridge economically. But the distinction between physical necessity and economic viability has rarely been clearer.

The old fossil business model depended on scarcity pricing and high utilisation. The new system is re-optimising around low-marginal-cost renewables supported by flexible storage and, increasingly, longer-duration options. Once that re-optimisation begins, it becomes self-reinforcing: renewables depress average prices, batteries monetise volatility, and thermal plants are pushed towards infrequent use — exactly the operating profile that is hardest to finance without explicit support.

The decisive question is no longer whether the transition happens. It is who builds fast enough to capture the upside — and which economies are left defending an “always-on” model that the cost curve has already begun to price out.

You may have an interest in also reading…

Trump Targets Wall Street Landlords, Putting Private-Equity Underwriting on Notice

A proposal to bar large institutional investors from buying single-family homes has jolted real-estate equities and reopened a long-running political

Q&A with the Executive Secretary of the UNCDF: Judith Karl

How would you sum up in three single words what characterises your team at UNCDF? Innovative Nimble Trusted What are

‘Sanaenomics’: The Abenomics 2.0 Shift from Deflation to Security

The economic platform of Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, quickly dubbed ‘Sanaenomics’, is not a radical break but a clear continuation