OECD: Only Scale and Development Impact Will Help Us Reach the SDG Mountain Summit

The development community is used to responding to crises but current events, not least COVID-19, have put the SDGs further out of reach. The private sector is recognised as a key contributor to delivering the SDGs by the development community and has shown a growing investment appetite since their launch in 2015. The Private Sector have also been engaged by donors through a number of approaches, blended finance being one that has increasingly gained traction. Blended finance is the strategic use of development finance for the mobilisation of additional finance towards sustainable development in developing countries.

The financial facilitator between the demands of the SDGs and private sector investment interest of investing in the SDGs could be another characterisation of blended finance. Facilitating the demand for aligning investments with goals of the SDGs and needs of economies that are growing and developing rapidly yet where many of the SDG gaps are the most significant, is where blended finance comes in. However, for Blended Finance to work effectively two key outcomes are required for delivery: – scale and impact.

The SDGs represent a significant mountain for development finance to scale. Currently the development system is failing to mobilise at scale, and channel funding to the countries and sectors that need it most. Over the period 2012 to 2020 more than USD 300 billion was mobilised by official development finance interventions, including ODA. Since the establishment of the SDGs in 2015, mobilisation did increase a stellar 20% the following year. In 2020, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, private finance mobilisation also slightly increased (by around 6%) compared to 2019. However, this is from a low base and though growth significant we are not at the scale necessary for solving the SDGs.

The same unevenness we see in overall mobilisation volumes between LDCs/LICs and UMICS is reflected in the different levels of funding directed to social and more commercial components of economies. For instance, Low Income Countries (LICs) and Less Developed Countries (LDCs) mobilised only USD 4.7 billion or 12% of the total mobilisation between 2018-2019. This stands in contrast to Upper Middle-Income countries (UMICs), who, in the same period, mobilised USD 19.5 billion, or 48% of the total.

Effectively mobilising the private sector has typically fallen to Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and Development Finance Institutions (DFIs). These institutions have recognisable structures, financial instruments and skills set that the private sector can most easily collaborate with. Moreover, as they understand risk and development they are structured to engage on financial transactions with varying levels of risk and returns. Many MDBs and DFIs have a credit rating which gives them enhanced funding raising and credit support, while a portfolio approach to investment ensures that project risks are effectively distributed across balance sheets. Meanwhile, donors need to work with these DFIs and MDBs and provide them with the political and financial incentives necessary for them to capitalise on the private sector turn towards Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) and SDG-lens investing.

Securing Scale

Blended finance now represents an established part of the development finance architecture, with a growing number of development actors across the spectrum committed to designing new approaches and structures. Within this, Green, Social and Sustainability and Sustainability-linked (GSSS) bonds have emerged as an important asset class. GSSS Bonds are fixed-income instruments that can helpensure finance targets the SDGs with the necessary scale and development impact needed. For example, Sub-Saharan Africah is characterised largely by a private equity investments and bank lending rather than debt market instruments and limited stock markets in order to raise capital. Equity tends to have a short-term perspective and bank finance is limited in reaching the necessary scale. The SDGs meanwhile, are long term challenges that require long-term investors with stable pricing and predictable exits. GSSS bonds typically generate the long-term returns that match the liabilities of pension and insurers. Sovereign issued GSSS Bonds allows the government, to access private sector capital and pay for new things such as green power generation. Further details on the potential of scaling the GSSS Bond Market is presented in this OECD report[1].

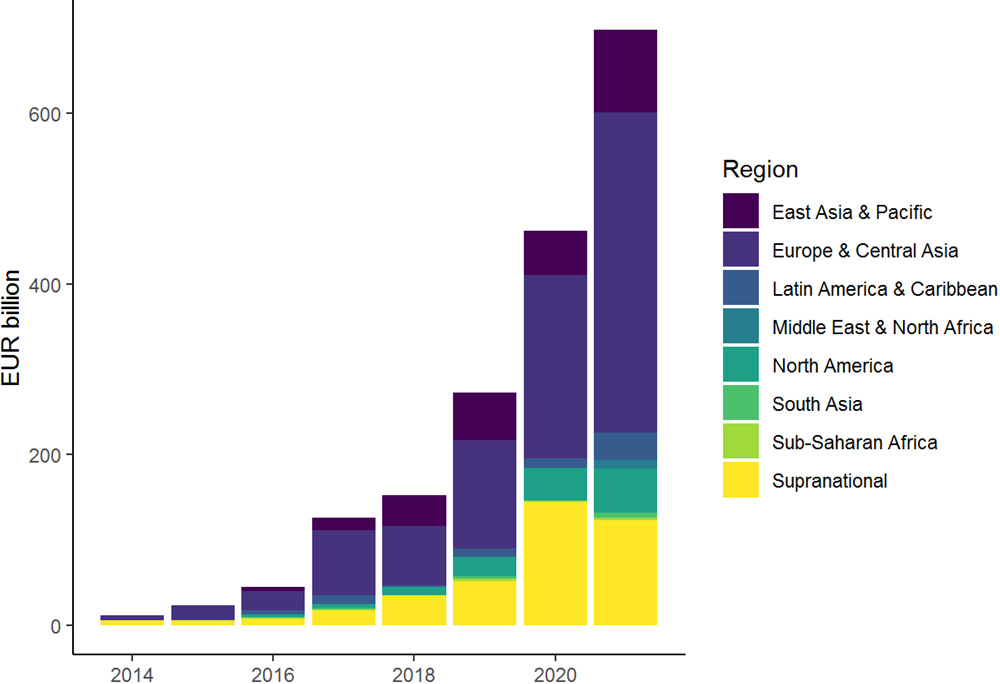

DFIs and MDBs are key actors in issuing GSSS bonds in their home markets but also importantly in developing countries. The figure below demonstrates that despite the rapid growth in the global GSSS bonds market, sub-Saharan Africa accounts for only a fraction of overall bonds issued. Increasing support from DFIs and MDBs in this region could help to scale up the market there as well

Annual issuance amounts of GSSS bonds (EUR billion). Source: OECD calculations based on data from LGX DataHub

While many DFIs and MDBs are already making use of GSSS bonds, further issuance could be constrained by the need for equity injections or the risk that credit ratings could be downgraded. However, greater issuance would help in considerably expanding balance sheets by allowing DFIs and MDBs to undertake more blended finance transactions, thereby helping to address the need for increased breadth of financial capacity and depth into specific sectors. A body of knowledge has been developed that highlights the ability of MDBs to expand lending without impacting the credit ratings or having minor impact in relation to their credit rating while significantly increasing balance sheet capacity (Humphrey, 2020[18]) (Banca d’Italia, 2019[19]). Even without touching the politically charged question of credit ratings, donors, DFIs and MDBs could join forces and work more efficiently to deliver the GSSS bond market. For this to happen, donors need to set DFIs and MDBs the necessary incentives.

In practice, the creation of local GSSS bond markets would provide the financial capacity to fund SDG-relevant projects. Typically, these projects are in local currency, matching revenues with local financing requirements. DFIs and MDBs can, at the local level, assist the issuance of GSSS bonds through blended finance, thereby increasing the pipeline of projects that can be aggregated to issue as GSSS Bonds. In regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, this would enable greater transparency and disclosure. This also includes debt transparency and ensuring the bonds are effectively delivering the right projects.

Scale in GSSS bond market will require co-operation across several development actors to ensure the necessary number of projects. For example, greater co-operation amongst DFIs and MDBs on bundling projects in sectors and across regions would help in developing the necessary aggregation for issuance and diversification for institutional portfolios. Co-operation not competition is therefore necessary. The DFIs and MDBs need to bring more projects to market, including targeting key countries and sectors. The GSSS bonds need to be considered as supporting all MDB or DFI activities, including investments in LDCs and Social Sectors. Capital provided by GSSS bond issuance should have the same goals as Official Development Assistance, in terms of leaving no one behind. Donors can be key actors in supporting DFIs and MDBs as issues of GSSS bonds and through blended finance and capacity building deliver help to deliver the necessary pipeline of projects for a bond issuance.

Need for Impact

DFIs and MDBs by sharing best practices in setting up eligibility criteria for the projects that underpin the bonds, as well as establishing allocation and impact reporting practices in these markets, DFIs and MDBs can help strengthen market discipline. DFIs and MDBs can also provide technical assistance to issuers. They can also support developing countries to set up the robust frameworks within which to select and implement green, social and sustainable projects that underpin the bond. This is a key requirement for bond issuers to obtain a GSSS label. As some DFIs and MDBs are issuers of GSSS bonds, they can also act as role models and standard setters. IFC, for example, has issued several local-currency GSSS bonds in emerging markets.. This can help to shift investor focus to the region and encourage other GSSS bonds issuers to follow suit.

Pursuing investments in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa without clarity on the development impact remains a challenge. This combined with a lack of platforms from listings on stock markets and dominance of private equity results in a lack of transparency that otherwise would encourage the financial markets to grow. Without more robust data on the development impact of investments, we cannot effectively channel mobilised finance to the geographies, sectors and people in most need.

A framework with the potential to help policymakers and practitioners alike is the OECD UNDP Impact Standards for Financing Sustainable Development. At the highest level, the OECD-UNDP Standards represent a best practice guide and self-assessment tool to help actors working in development finance manage projects in ways that generate positive impact on people and the planet, and improve the transparency of development results. While not directly focusing on the outcome of investments into GSSS bonds, the focus on changing incentives and emphasising the need to manage primarily for impact can help shape GSSS bond impact approaches.

GSSS bonds allow greater deal flow for development actors. The direct effect of this is more transactions and pipelines of projects delivering development. To facilitate this, development actors and the private sector need to work together in a joined-up fashion. At present, the necessary scale and impact, which would create the GSSS Bond markets of tomorrow, does not exist.

By Paul Horrocks, Jieun Kim and Esme Stout

[1] Scaling up Green, Social, Sustainability and Sustainability-linked Bond Issuances in Developing Countries (https://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DCD(2021)20&docLanguage=En)

You may have an interest in also reading…

CBI Says ‘Get Major Projects Moving to Protect the Recovery’

Ahead of the Wednesday June 26th spending round, the Confederation of British Industry reiterated its call for the Chancellor to

CORDET Capital: Unlocking the Potential of Northern Europe’s Lower Mid-Market

With a sharp focus on delivering compelling risk-adjusted returns, CORDET Capital has positioned itself as a distinctive force in private

Janamitra Devan: The Innovation Imperative

Overcoming the Myths and Recognizing the Realities of Innovation, Job Creation and Prosperity By Janamitra Devan Innovation drives competitiveness, and