Bob Dylan: Things Have Not Changed

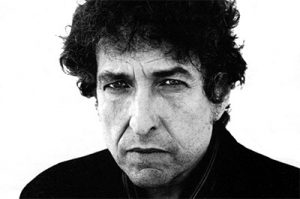

Bob Dylan

In 1963, The National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee handed its annual Tom Paine Award to Bob Dylan for his contribution to the fight for civil liberties. The 22-year old Dylan did in fact show up to its Bill of Rights dinner to receive the award in person. In a rambling acceptance speech he admonished the committee members and their patrons for being old, dismissed the million-man march for being too polite and too proper, and somehow managed to round off his address by expressing empathy for the man who shot dead President Kennedy not three weeks prior. At that point the progressively–minded dinner guests realised that polite silence to hear what the younger generation had to say would amount to tacit approval and took the nervous and slightly drunk singer out of his misery and booed him off the podium.

Mr Dylan’s subsequent relationship with ceremonies isn’t any less awkward. At best gracious but vaguely aloof (cocking an eyebrow behind aviator glasses as President Barack Obama placed the presidential Medal of Freedom around his neck), and at worst openly dismissive (describing an honorary degree from Princeton as a loss of credibility). So maybe the members of the Swedish Academy considered it somewhat of a relief as Ambassador Azita Raji approached the lectern during their banquet last December.

“For many, Bob Dylan being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature was a long time coming; for others it was a pathetic or even cynical pandering to popular culture.”

Controversy isn’t entirely novel to the world’s most prestigious literary prize. Following the delayed announcement last October, however, the accusations weren’t of the academy’s choice being too obscure, too politically disagreeable, or too European. Rather the supposed disqualifying factor was one more fundamental: the work just isn’t literature. For many, Bob Dylan being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature was a long time coming; for others it was a pathetic or even cynical pandering to popular culture. Within hours, the world’s news outlets had had op-eds posted on their websites, often both those jubilant and those stupefied by the news, each backed up by their team’s high profile tweets. For team jubilant: Salman Rushdie, whose history with the Swedish Academy is an uneasy one to say the least, seemed to have preempted some of the criticism when he tweeted:

“From Orpheus to Faiz, song & poetry have been closely linked. Dylan is the brilliant inheritor of the bardic tradition. Great choice. #Nobel”

And for team stupefied Irvine Welsh offered an undeniably eloquent assessment with:

“I’m a Dylan fan, but this is an ill-conceived nostalgia award wrenched from the rancid prostates of senile, gibbering hippies.”

Seemingly the only one not weighing in was Dylan himself. Granted, his isn’t exactly the most lively of twitter feeds, consisting usually of just promotional material (though recently a baffling premature message of condolence for pop star Britney Spears), but the full two weeks it reportedly took for someone at the Academy to get Mr Dylan on the phone did leave some accusing the songwriter of arrogance, and some detractors of the academy’s decision cautiously optimistic that the man himself was in fact an ally and would ‘pull a Sartre’ and decline the award. The subsequent news that the artist would not be attending the ceremony in Stockholm exacerbated the accusations of arrogance.

In his place, singer songwriter Patti Smith accepted the award during the ceremony with a rendition of A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall during which she charmingly fumbled the second verse, with the aforementioned Ambassador Azita Raji delivering a warm, considered, and genuinely gracious acceptance speech prepared by Dylan. Gracious, to a point. He did in no uncertain terms compare himself to Shakespeare. Then again, if that’s ever one’s prerogative, it’s while accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The Nobel Prize for Literature is not awarded on the basis of any single work that is considered great literature, rather it is in recognition of a person who has, as per the wording of Alfred Nobel’s will, produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction. This is rather vague language, the interpretation of which is left to the 18 members of the Swedish Academy. Those 18 members named Bob Dylan for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition. He is the first singer songwriter to be awarded the prize.

Dylan is something more than all other popular singer songwriters. He is an indispensable node of the American canon without which one cannot understand western culture of the 20th century. His musical style and subject matter initially drawn from the progressive folk music revival, American traditional ballads, gospel, and blues; his language and form were also informed by romantic, modernist, and beat poetry, and a decent amount of eisegesis. He is defined by his time as much as he defined it, but you don’t get thrust upon you the moniker voice of a generation without finding new modes with which to express some universals. There is a Dylan line for almost every shade of melancholy, of righteous anger, of optimism, of tempered self-doubt, of amusement. Yes, and is as much impoverished when removed from its guitar melody and harmonica, as is Shakespeare when read quietly to oneself complete with stage directions. That does not make them any the less literature.

Author: John Marinus

Dylan references the Tom Paine award incident in As I Went Out One Morning, on his eighth studio album John Wesley Harding which was released in 1967. In it the character Tom Paine apologises to the protagonist as a chained woman (who in an admittedly ad hoc interpretation could be read to represent recognition) insistent on him taking her with him. While in his first four albums he defined and repeatedly reinvented the protest song and the story ballad for his time, and his subsequent three albums Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde consisted mostly of mad vivid evocative ballads seemingly written by a man not so much inspired as possessed, resisting interpretation through sheer sensory overload, John Wesley Harding, and most notably its eliotian masterpiece, All Around The Watchtower, are far more restrained pieces with greater reliance on poetic device. This is Bob Dylan developing in a way that can categorically be described as literary.

Recognition is not chiefly meant to serve the recipient but rather society as a whole (which seems pretty obvious when stated like that). Making it all the more bizarre how many serious articles argue that Bob Dylan doesn’t need the recognition or the prize, and that the academy squandered an opportunity to shine a spotlight on a lesser known author. Bringing to the global foreground the many deserving literary figures is certainly worthwhile, but that simply isn’t the purpose of the Nobel Prize.

Fearing not that I’d become my enemy in the instant that I preach (My Back Pages), I’ll resist ending on a Dylan line.

You may have an interest in also reading…

From Lebanon to Brazil – Joseph Safra

A Global Presence The Safra family fortune – today expressed in billions of dollars – originated on the dusty tracks

Attitudes Towards Remote Working: Employer vs Employee Perspectives and Economic Implications

The landscape of the workplace has been irreversibly transformed by the rise of remote working, a shift accelerated by the

Where are We Going? Nowhere, Fast, According to Travel and Tourism Stats

Whether domestic or international, business or pleasure, travel is an integral part of modern life — no longer just a