Otaviano Canuto: Macro-economic Policy Change – We’re Not in Kansas Any More

The possibility of multiple financial shocks lies ahead.

Three significant changes to the macro-economic policy regime in advanced economies have unfolded in the past two years.

Fears of a chronic insufficiency of aggregate demand as a growth deterrent — which prevailed after the 2008 global financial crisis — have been superseded by supply-side shocks and inflation. As a result of that, the era of abundant and cheap liquidity provided by central banks has given way to higher interest rates and liquidity squeezes. Finally, also because of those changes, there was a strong devaluation of financial assets in 2022.

Fears of a chronic insufficiency of aggregate demand as a growth deterrent — which prevailed after the 2008 global financial crisis — have been superseded by supply-side shocks and inflation. As a result of that, the era of abundant and cheap liquidity provided by central banks has given way to higher interest rates and liquidity squeezes. Finally, also because of those changes, there was a strong devaluation of financial assets in 2022.

A triple structural change in the macro-economic policy regime in advanced economies has taken place, as compared to the post-global financial crisis period.

Some believe that the era of ultra-low interest rates and low inflation is gone; others believe the situation is reversable. Quantitative tightening and higher basic interest rates by central banks became the new norm, as a sort of normalisation of monetary policies.

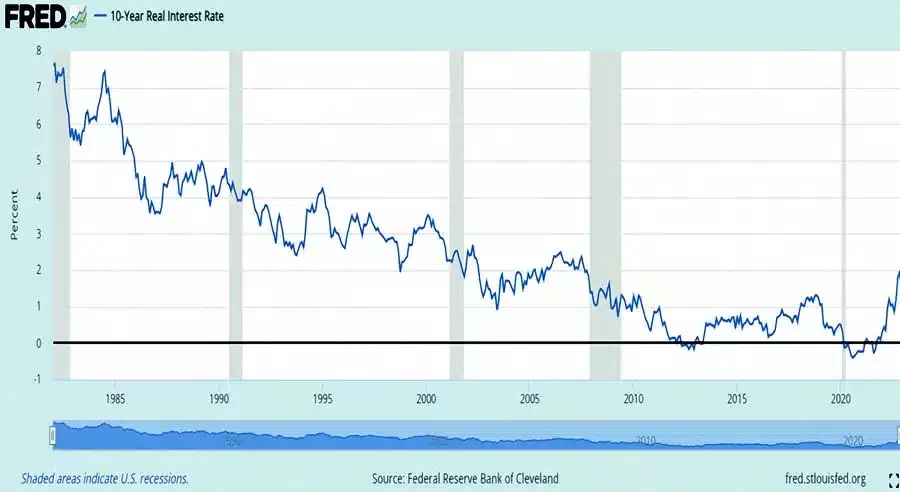

Figure 1: U.S. 10-Year Treasury Real Interest Rate

There are now fears about further financial shocks. Starting in 2021, inflation in the US and Europe rose to the highest levels in decades. US consumer prices rose by about seven percent in 2022, the highest in four decades. In Germany, 2022 ended with an annual inflation rate of 9.6 percent, perilously close to the first double-digit inflation since 1951.

The surge is explained by succession of supply and price shocks, while a robust recovery of post-pandemic demand was taking place. In 2023, rising interest rates are threatening to push the global economy into recession.

Many analysts initially viewed the inflation as transitory, and reversible. Now it is acknowledged that excess demand, relative to supply, called for restrictive central bank policies. Doubts are emerging about how high, and for how much longer, interest rates will have to go to soften labour markets, and prevail over the resistance in services inflation. Are these symptoms of a business cycle, or some structural change that means an end to low inflation and low interest rates?

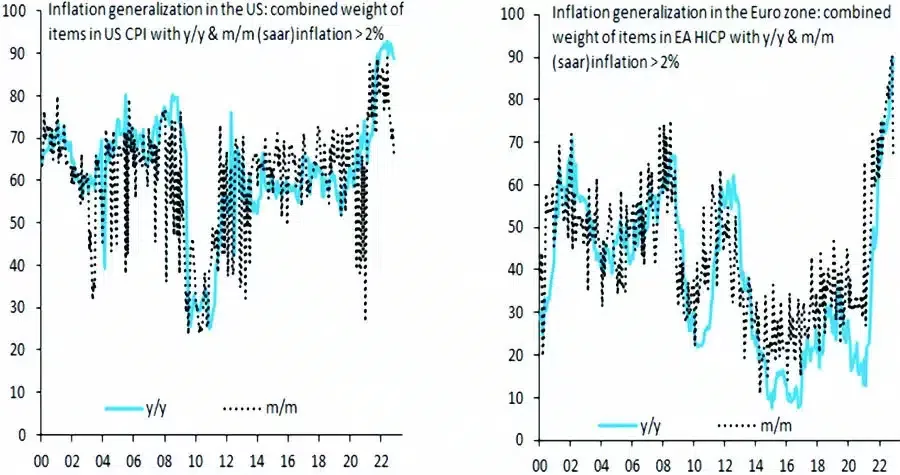

Figure 2: Less Generalised Inflation in the U.S. and Europe. Source: Brooks et al (2022).

In the years following the 2008-09 global financial crisis, sluggish economic growth was attributed to insufficiency of aggregate demand. Multiple hypotheses were established: hangovers from the financial crisis, income concentration, the exhaustion of the technological waves of previous decades, and demographic dynamics.

There were long period of low interest rates (Figure 1), accompanied by a flood of liquidity from central banks via quantitative easing programs (purchases of government bonds, mortgages, and, in the euro area, private assets) after the 2008-09 crisis. That offset the relatively low use of expansive fiscal policies. But the fiscal policy signal changed with the emergency government support during the pandemic.

Multiple shocks showed that supply, not demand, was causing the difficulty. There has been a decline of labour market participation, especially in the US. Certain segments of the population have left the workforce at unusually high rates, either by choice or necessity. This has been compounded by disruptions in global labour flows, as fewer foreign workers have received visas or are willing to migrate.

Figure 3: 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Minus 3-Month Treasury Constant Maturity

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered food and energy supply shocks. Governments intensified their weaponization of trade, investment, and payment sanctions — worsening tensions between the US and China.

Some global supply chains have been rewired to aim for more “friend-shoring” and “near-shoring”. The perception of geopolitical risks and the greater frequency of extreme weather events are leading companies to pursue resilience over cost efficiency. Less quantity-responsive and more price-responsive supply chains could become the norm.

The energy transition is also intrinsically inflationary. Changes in the scope of globalisation, labour shortages and climate change have put into question the belief of a continuing era of low inflation and interest.

Looking ahead:

Inflation rates seem to have peaked in the US and Europe (Figure 2), but the tightness of labour markets and the downward resilience of core inflation in services are potential dampening factors. Mild or hard recessions loom on both sides of the Atlantic. The inversion of the US yield curve (Figure 3) suggests this to be the case.

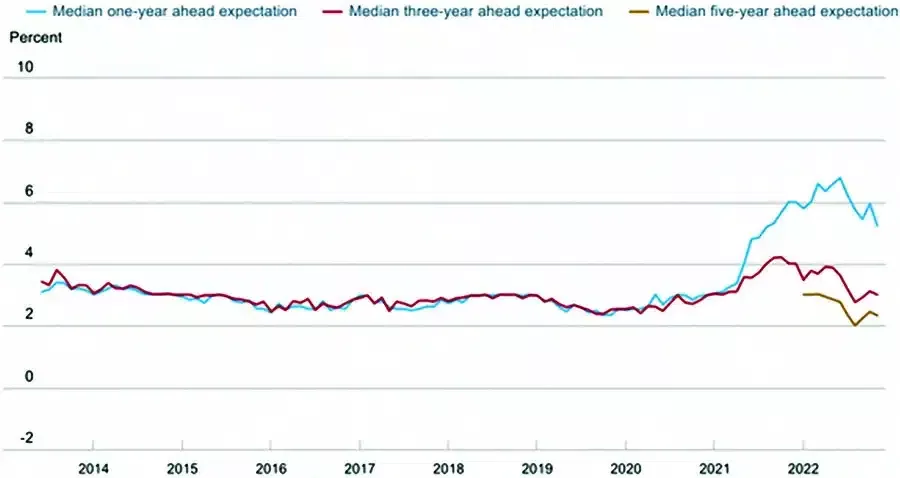

Figure 4: U.S. Inflation Expectations. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Survey of Consumer Expectations.

Inflation is expected to remain high in 2023. But expected medium-term inflation remains low, which may be interpreted as a sign of inflation so far not becoming entrenched (Figure 4).

Goodhart and Pradhan have argued that demographic dynamics and a retreat from globalisation mean higher inflation and higher interest rates over the long term. In contrast, Blanchard believes that the factors that have led to low real interest rates on safe assets will return once the current inflationary shock is over.

The frequency and intensity with which (relative) deglobalisation, geopolitical events, and climate change bring new shocks will determine whether the 2021/2022 reconfiguration of demand-supply interaction will persist. And whether US and Europe return to the path on which a mismatch between wealth and creation of new assets tends to lead interest rates again to low levels.

The End of Boundless Liquidity

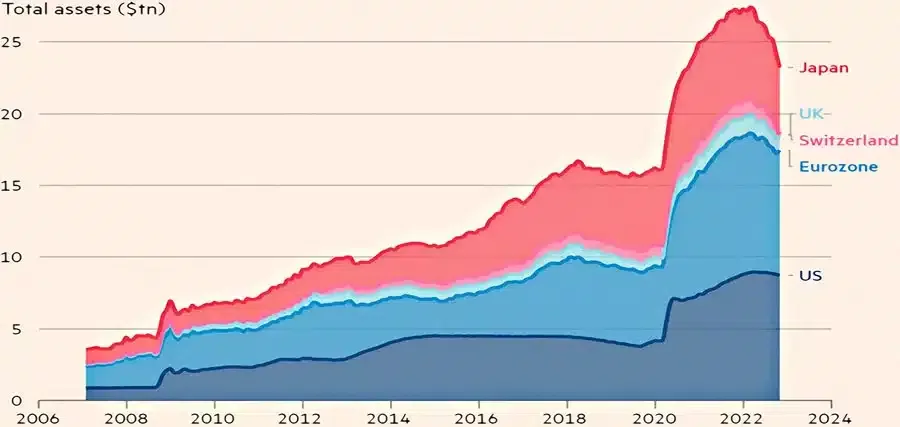

For years, central banks have responded to virtually any sign of economic weakness or financial market volatility by putting more money in. During the pandemic, central-bank balance sheets made huge additional jumps relative to the trend since the global financial crisis (Figure 5).

But as they extended what were supposed to be time-limited interventions, some collateral damage was inflicted. Liquidity-laden financial markets became dissociated from the real economy.

In the US “taper tantrum” in 2013, the-then chair of the Fed, Ben Bernanke, announced that the institution would start planning the end of quantitative easing — and ended up reversing this course six weeks later. It also occurred in the fourth quarter of 2018, when another fed chair, Jeremy Powell, had to make an embarrassing about-turn from his mild quantitative tightening because the markets got choppy.

Figure 5: Central Bank Balance Sheets. Source: Refinitiv / Financial Times

The diagnosis of inflation as transient gave way to promises of quantitative tightening in earnest — and raised interest rates. The Fed continued to inject liquidity into the economy until March 2022, gradually shrinking its balance sheet starting in June.

It also finally began to raise policy rates. It switched to a series of steeper hikes, including a record four successive ones of 0.75 percentage points between June and November 2022, and ending the year with another 0.50 percentage points. It should raise the base rate by 0.25 percentage points two or three more times in the first few months of 2023, and leave it there for a while.

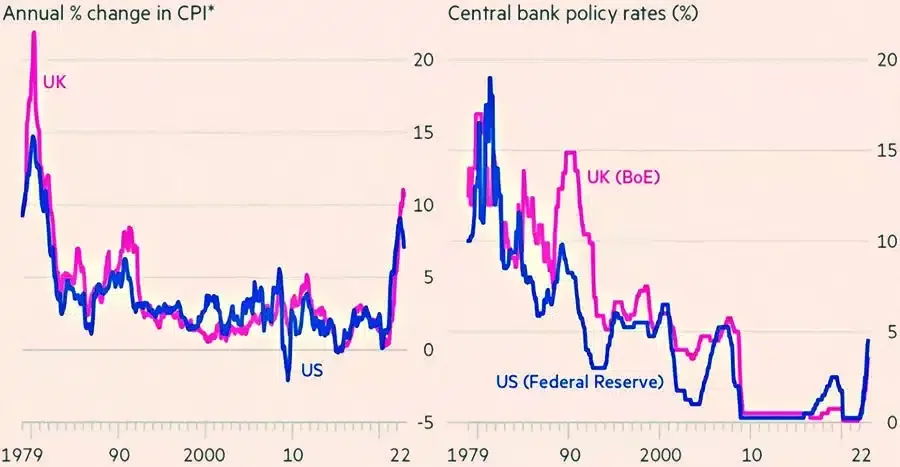

US low inflation and ultra- low interest rates have been replaced with higher inflation and interest rates (Figure 6). The European Central Bank is moving in the same direction, though with less intensity.

Figure 6: U.S. CPI inflation and Fed Policy Rates. *UK RPI Pre-1989. Source: Keith Fray, Steven Bernard, Matthew Brayman and Justine Williams (2022). War, inflation and tumbling markets: the year in 11 charts, Financial Times, December 29.

Looming Fragility

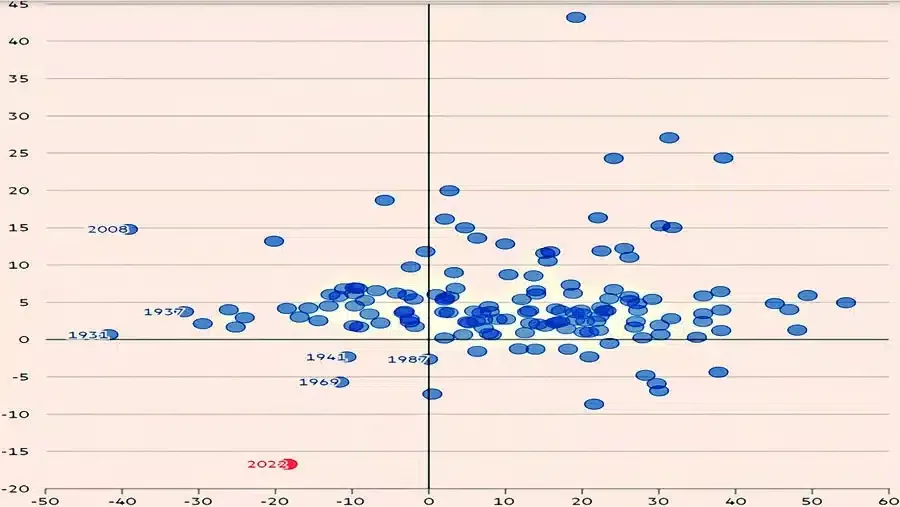

If 2022 was a year of equity and fixed-income devaluation, the financial year ended with losses of more than $30tn in equities and fixed-income bonds. Figure 7 shows how negative a year it was for investors, in both stocks and bonds. The macro-economic slowdown in 2023 is likely to also lead to lower overall asset yields, especially from stocks.

Corporate debt increased in the years of low interest rates and abundant liquidity. Although analysts suggest that there is no generalised vulnerability in terms of mismatches of rates between assets and liabilities, there are multiple points at which some sudden disappearance of liquidity could lead to dramatic adjustments and insolvencies.

The OECD in 2022 highlighted major financial market developments, spill-overs to credit risk, and rising vulnerabilities in several market segments as a reflection of tighter monetary conditions, slower global growth, higher inflation, and geopolitical tensions.

A metamorphosis in financial flows took place during the era of easy money, with a significant part of global financial activity shifting after the global financial crisis from highly regulated banks to less regulated and constrained entities, including asset managers, private equity funds, and hedge funds. Non-bank institutions replaced banks in financial intermediation, and a morphing and migration of risk took place.

After the 2008 financial crisis, high capital requirements were established, limiting banks’ activities; the banking system was de-risked. But the newly prominent intermediaries are not likely to maintain strong resilience against sudden and sharp changes in the cost of borrowing, or access to finance.

The post-2008 crisis reforms, while targeted at reinforcing financial stability, may have replaced counterparty risk with liquidity risk. Shocks on asset prices may be propagated by intermediaries being obliged to shrink their holdings, exacerbating those shocks via transmission and contagion.

The displacement of counterparty risk into liquidity risk appears in several forms. In US Treasury markets, banks used to perform a critical warehousing role, especially in the short-term lending “repo” market. Stricter capital rules have led them to move to other, higher-margin business lines, while other market participants have not yet filled the void. When volatility rises, hedge funds and high-frequency traders keep a certain distance.

Figure 7: Total Nominal Return in U.S. Stocks and Bonds, 1871 to 2022 (percent). Source: Keith Fray, Steven Bernard, Matthew Brayman and Justine Williams (2022). War, inflation and tumbling markets: the year in 11 charts, Financial Times, December 29.

The emphasis on collateral has also exacerbated instability by increasing selling pressure. The UK gilt market meltdown in October 2022 is a prime example: pension funds had bought derivatives as part of a liability-driven investing. Then, after Liz Truss’s newly inaugurated government announced a plan for massive unfunded tax cuts, government bond yields soared, suddenly hitting some of the country’s highly leveraged pension funds.

When gilt prices fell sharply, they received margin calls requiring them to post more collateral. The price was driven down, leading to more margin calls: a vicious circle. Were it not for the emergency intervention of the Bank of England, the withdrawal of the Truss government’s proposal, and the government’s eventual downfall, the forced sale of bonds by pension funds could have turned into a major financial crisis.

Another potential form of illiquidity has arisen in recent years as investors have moved beyond bank accounts, stocks, and bonds. In times of market stress, funds focused on real estate, private credit, and others have been hit by more redemption requests than they can easily handle.

The BIS Quarterly Review examined how poor liquidity conditions across market segments have kept asset price volatility elevated, and contributed to swings in global financial conditions. The report focuses attention on signs of fragility in the markets for agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS), dedicating a box to the risk of liquidity disruptions.

There are also non-transparent off-balance-sheet risks in both the bank and non-bank financial sectors. The BIS review of December contained a chapter by Claudio Borio, Robert N McCauley and Patrick McGuire on “huge, missing and growing” Dollar debt in foreign exchange swaps, forwards, and currency swaps.

The fragility of the financial system has implications for the work of central banks. Instead of facing their basic dilemmas — reducing inflation, or maintaining economic growth and employment — they now face the task of reducing inflation, maintaining growth and jobs, or guaranteeing financial stability. As growth slows, monetary tightening is prolonged, and illiquidity bouts exacerbate financial fragility, central banks might be forced to try to reconcile their quantitative tightening and interest rate hikes with interventions to provide liquidity at key points of the system.

Whatever the duration of the new policy regime may be, we are no longer in Kansas with respect to supply versus demand, monetary policy, and financial stability.

First appeared at Policy Centre for the New South.

About the Author

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a visiting public policy fellow at ILAS-Columbia, and principal of the Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at University of São Paulo and University of Campinas, Brazil. Otaviano has been a regular columnist for CFI.co for the past ten years.

Follow him on Twitter: @ocanuto

You may have an interest in also reading…

U.S. Trade Deficit and Consumer Sentiment Rise

The United States trade deficit widened in November to its largest point in five months, prompting some economists to slightly

Anthony Scaramucci: Mooching Towards Washington, With No Polyester Suits in Sight

Entrepreneur and author Anthony Scaramucci has seen plenty of ups and downs — and the US presidency may not be

The Saudi Arabian Stock Exchange: Opening to Foreign Investors in June

As of June 15th this year, the largest stock market in the Middle East– Saudi Arabia’s Tadawul – will be