Robed Culprits and the Struggles of Corporate America

Blame the US Supreme Court. The oftentimes maddingly short-sighted behaviour of Corporate America does not necessarily spring from the narcissism of CEOs but stems from unambiguous case law. Almost invariably, US courts have upheld, clarified, and tightened the fiduciary duty of corporate executives as the expert stand-ins for shareholders.

Blame the US Supreme Court. The oftentimes maddingly short-sighted behaviour of Corporate America does not necessarily spring from the narcissism of CEOs but stems from unambiguous case law. Almost invariably, US courts have upheld, clarified, and tightened the fiduciary duty of corporate executives as the expert stand-ins for shareholders.

Reduced to its most basic form, a fiduciary relationship is deemed to exist when one party entrusts another with the management of its affairs. This is different from, say, a transactional relationship in which parties may reasonably be expected to act in ways that further their own interest.

It is not the job of judges to instruct CEOs on how to run a publicly traded company. With their rulings on fiduciary duty, the courts merely seek to clarify the responsibilities of the parties to a fiduciary relationship. Though legal rulings are open to interpretation in much the same way that statistics may be used to prove almost any point, the consensus is that corporate management must keep its eye trained on the bottom line and work tirelessly to maximise the return on the capital invested by shareholders. Any deviation from this principle offers fodder to lawyers eager to argue a breach of trust.

This helps explain why most US corporates are reluctant to include sustainability and environmental concerns in their operational processes. Any long-term planning, or the consideration of interests other than those of shareholders, distracts from the duty to maximise profits. This is, in a nutshell, how the ‘next quarter’ came to rule supreme – and why a great many otherwise admirable companies have come to hollow out their finances by showering shareholders with cash.

Many of those corporations are now teetering on the brink of insolvency and demand the taxpayer come to the rescue. The sorry plight of Corporate America in times of corona has resulted in a form of ‘involuntary blackmail’: the taxpayer is being told that without his/her money, businesses will fail, and the economy will tank even deeper than it already has. Without a sufficiently large bailout, the pandemic will rage with the destructive force of a tornado across the corporate landscape.

A major disaster is, of course, not the moment to remind victims of past errors in judgment. In 2008, few people professed a deep-seated love for the financial services industry, yet nearly all agreed that banks needed to be rescued in order to prevent an even greater catastrophe. The pandemic is no different, though it cannot hurt to remember why only a very few large corporations have enough ready cash available to weather the present near perfect storm.

Berkshire Hathaway, Facebook, and Apple are amongst the select few US companies that have managed to resist the clamour of shareholders for large payouts. Both kept large cash reserves that not only allows these companies to survive the pandemic without appealing to the government for help, but also enables them to seize any opportunity arising out of the rubble.

Pundits often point to Berkshire Hathaway CEO Warren Buffett as the posterchild of stock buybacks, a cause he has championed for close to fifty years. Less well advertised are Mr Buffett’s warnings that the repurchase of stocks is only admissible when the company keeps sufficient cash on hand to cover its operational and liquidity needs.

In his 2011 letter to shareholders, Mr Buffett added that buybacks should only take place at a time when the company’s stock is trading at a ‘material discount’ to the intrinsic value of the business, ‘conservatively estimated’. The following year, Mr Buffett expanded on the latter bit of his advice by explaining the obvious: “It’s hard to go wrong when you’re buying dollar bills for 80¢ or less.”

As usual, there is little anyone could argue against the lessons in business logic and pure reasoning broadcast annually from Omaha, Nebraska. However, a fair number of stock buyback initiatives ultimately went awry. Buyers’ remorse is now reaching an all-time high. Once the unexpected happened, as it was bound to do at some point, the party ended in tears. That is because the hosts didn’t listen to the sage.

According to data gathered by S&P CapitalIQ, a global financial intelligence bureau part of McGraw-Hill, companies included in the S&P 500 index increased their repurchases of stock between 2016 and 2019 by 30 percent to about $2 trillion. Including dividends, these companies returned some $3.5 trillion to shareholders – an amount roughly equal to their combined net income over the period. An often-overlooked indicator, the net debt to gross earnings (EBITDA, earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortisation) ratio also deteriorated significantly during the last three years for which data are available. That number now stands at 1.8, indicating that corporates took on an exceptionally high level of debt – all the while forking large amounts of cash over to shareholders.

Whilst Mr Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway always maintains a famously large pile of readily deployable cash, many others pushed stock buyback programmes to far beyond the point of reason. Both Boeing ($53 billion) and American Airlines ($13 billion) would now love to have some of the capital they released to shareholders. The companies, in line for large federal bailouts, represent but two of the more egregious examples of irresponsible buyback schemes.

Another one is Yum Brands, parent to the KFC and Taco Bell fast-food chains, which actually borrowed heavily to buy back its own stock. Over the last five years, Yum Brands spent an estimated $15 billion to reward shareholders whilst its debt load soared from the equivalence of 40 percent of company assets to well over 200 percent. Earlier this month, the company was forced to raise cash via an emergency bond issue. It managed to place some $600 million at a yield almost double that of previous issues. Whilst Yum Brands proudly announced that it has not requested government support, the company said that its thousands of franchise holders could apply for federal aid. An initiative of the highly lucrative fast-food industry to claim up to $145 billion in relief was quietly shelved after eyebrows were raised in Congress.

Over the years, chief executive Laurence Fink of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, repeatedly warned about the dangers of ‘short-termism’, a phenomenon he detected in the upper echelons of management at many large companies. Mr Fink worried that the fascination of CEOs with the next quarter’s results undermines not only research and development efforts but also dampens future growth prospects.

However, most CEOs have little choice and must operate in a restricted environment: at listed companies, management must act first and foremost on behalf of shareholders and only after their interests have been secured can they look at what’s best for the company. Though both interests – those of the company and its shareholders – often seem perfectly aligned, in practice they are not as stock prices are determined mostly by corporate performance in the here and now, and only to the most minute degree by concerns over long-term profitability.

Thank the US Supreme Court for the ‘short-termism’ that defines Corporate America and now has come back to bite it. Once the pandemic is over, the time may be right to revisit the principle of fiduciary duty as it applies to the relationship between management and shareholders.

You may have an interest in also reading…

The Sudden Fall and Coming Resuscitation of Reaganomics

Trickle-down economics was counted amongst the first fatalities of the corona pandemic. The belief that government interference with the functioning

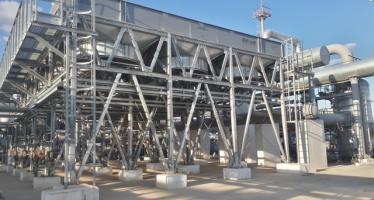

Uzbekistan ‘s Enter Engineering announces Covid years project updates and operations guidance

According to Ulugbek Usmanov, General Director at Enter Engineering: “Enter Engineering is involved in a variety of projects central to

Europe: Fig Leaves to Save Spain and Italy

Looking to score without breaking a sweat, European politicians of almost every ideological persuasion often turn on ‘Brussels’, assigning blame