James “Jamie” Dimon: How Not to Be a Good Banker

Jamie Dimon

The CEO, chairman and president of JPMorgan Chase has no shortage of supporters and fans. Just two years ago, James “Jamie” Dimon was named CEO of the Year. In its All-America Executive Team Survey, Institutional Investor has placed Dimon near the very top for five years running. This is one guy that knows how to impress.

With a pay package exceeding $23 million annually and excellent connections in the White House, Dimon has been hailed as “the best banker we’ve got” by no one less than President Obama himself. Still, Dimon has been caught lying quite a few times.

In 2012, he obfuscated trading losses amounting to well over $6 billion at the London office of JPMorgan Chase. A report by an US Senate investigative commission concluded earlier this year that Dimon misled both investors and regulators as to the extent of the losses caused by Bruno Iksil, a trader known as The London Whale. Dimon had earlier dismissed the losses as a “tempest in a teapot”.

Some tempest: The US Senate commission found that JPMorgan Chase had knowingly violated “massive numbers of key risk limits” and “neglected to disclose the truth to either regulators or the public.” These damning assessments of the bank’s behavior are cause for considerable worry.

JPMorgan Chase was one of the few big US banks that did not actually need a taxpayer-funded bailout when the financial crisis hit in September 2008. Even so, the bank was urged to accept $25bn to help assure markets that all big banks were safe and being well looked after by the Federal Reserve. JPMorgan Chase was the first of the nine taxpayer supported banks to hand back the full amount.

“JPMorgan Chase was one of the few big US banks that did not actually need a taxpayer-funded bailout when the financial crisis hit in September 2008. “

Dimon now seems to have concluded that risky behavior carries its own rewards. If things go wrong, a bailout will follow. If things go well, profits loom large. It’s the socialization of losses and privatization of profits. The fact that a single trader is allowed to expose its employer to over $6bn in losses on positions hard to unload at short notice, seems indicative of a culture in which deregulation has gone wild.

This has absolutely nothing to do with banking any longer. JPMorgan Chase is not providing the public with any discernible service by having traders make outrageously risky bets in order to chase a quick and easy buck or two. While it remains a formidable feat of financial engineering, bordering on alchemy, to create billions in profits out of thin air – or by shifting bucket loads of digits around the globe and seeing their number increase as they move – the monies thus created seldom if ever proof beneficial to the wider society. In fact they are detrimental to nations and their real economies (as opposed to bankers’ flights of fancy) inasmuch that its creation attracts the brightest young minds.

There is no doubt that Jamie Dimon has an absolutely brilliant mind. He might even be a kind of genius. It is, however, most regrettable that he didn’t choose to apply his intellectual and creative powers to, say, engineering, medicine or some other form of activity that actually produces real wealth and prosperity. And if you do insist on becoming a banker, then at least try to make an honest buck by facilitating investments in worthwhile human activities that give a good and decent return to the bank, its depositors and shareholders and to society at large. Risking billions in iffy schemes is not part of that equation.

You may have an interest in also reading…

Paolo Sironi, IBM: All Eyes on Financial Services Cyber-Resilience

No industry is fully immune from cybersecurity threats, from water pipelines to healthcare, financial services included. According to experts, regulators

The Franco-German Relationship Looks Set to Continue but Where Does This Leave the Greeks?

Newly-inaugurated French President Francois Hollande and German Chancellor Angela Merkel said on Tuesday they want Greece to remain in the

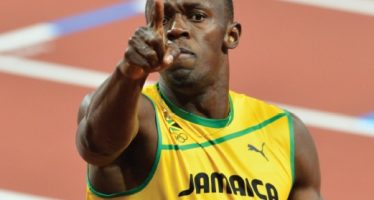

Usain Bolt: Nothing Left to Prove?

He has nothing left to prove? Perhaps so, but we identify in Bolt a hunger for continuous improvement. He wants