OECD: Latin America’s Outlook Clouded by Asia’s Slowdown and Financial Uncertainty

Mexico City: Angel of the Independence

The external scenario is less favourable for the region due to the downturn in global trade, the moderation in commodity prices and the increased uncertainty surrounding global financing conditions.

General Overview

The euro area’s weak economic performance, the slowdown in the Chinese economy and its effects on metal and mineral prices, and the impact that the normalisation of US monetary policy will have on international capital markets directly affect Latin American economies.

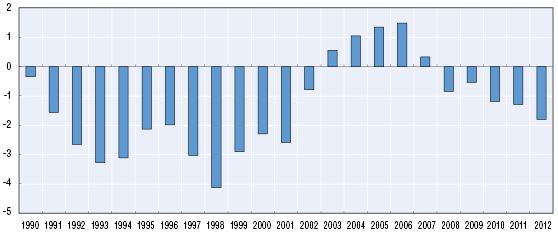

First, demand for exports of the region’s goods and services is forecast to decline due to more moderate growth in global trade. Second, while the prices of imports have remained stable, the prices of Latin American and the Caribbean’s main commodity exports have declined since 2012. These factors have contributed to the deterioration of the trade balance (Figure 1), which is lower than in the 1990s, but increasingly more uniform. At the one extreme are the net exporters of oil and gas, which have current-account surpluses, and at the other are the economies of Central America and the Caribbean, which are net importers of commodities and have current-account deficits of more than 10% of GDP. Finally, if the United States tightens its monetary policy, external financing will steadily become more expensive and capital outflows to the region will probably fall, resulting in greater uncertainty and more volatile capital markets.

“Several countries are converging towards their potential GDP from an expansionary phase of the business cycle.”

Although an increase in domestic demand could partly compensate the slowdown in external demand, many Latin American economies are converging towards their potential GDP following an expansionary phase of the business cycle.

Although many of the region’s economies have some monetary and fiscal space for an additional stimulus to compensate for temporary external shocks, the region is faced with a more permanent, widespread economic slowdown that makes it difficult to provide this kind of stimulus. Moreover, several countries are converging towards their potential GDP from an expansionary phase of the business cycle, and some are also faced with supply-side bottlenecks, making them vulnerable to domestic and external imbalances if there is an additional stimulus.

Figure 1: Current account as percentage of GDP of Latin America and the Caribbean. Source: Based on ECLAC (CEPALSTAT) data.

Previous episodes of economic instability in the region are a reminder to be vigilant of expanding domestic credit and changes in fiscal aggregates.

Credit relative to the size of the economy has grown rapidly in most Latin American countries in the last ten years, especially mortgages and consumer credit. The authorities should therefore monitor the amount of credit so they can prevent or mitigate potential booms, which lead to internal and external imbalances. They should take measures to ensure that the financial system remains solvent, avoiding excessive risk-taking and limiting the system’s procyclical nature. Moreover, although currents debt levels are sustainable under the baseline scenario, the fiscal space has shrunk considerably in various Latin American countries. This divergence between fiscal balances and indebtedness is the result of a series of factors, including currency appreciation and lower effective interest rates compared to the recorded rate of GDP growth. It is therefore important to design and implement fiscal reforms to create a larger fiscal space and to adopt measures to ensure continued access to sufficient levels of liquidity, whether by accumulating and holding international reserves or arranging contingent credit lines.

The current macro-economic context further highlights the structural challenges that remain, such as the imbalance between tradeable and non-tradeable sectors of the economy.

Commodities make up 60% of the region’s exports of goods, up from less than 40% at the beginning of the last decade (2000-10). Also, around half the increase in the value of Latin American exports in the 2000s was a result of commodity price rises, whereas in the 1990s it was mainly due to increases in the volume exported. Moreover, the surplus resulting from the concentration of exports in a limited number of commodities has also contributed to growth in domestic sales, which, in line with the decline in domestic industrial production, have led to a rise in imports. Consequently, manufacturing has slowed and the imbalance between the tradeable and non-tradeable sectors has widened.

The challenge of achieving sustainable growth and greater economic diversification comes at a time in which a new “middle class” is emerging.

After a decade in which economic growth was accompanied by a substantial reduction in poverty and improvements to inequality indicators, a “middle class” has emerged in the region. In the emerging economies this “middle class” will grow from 55% of the population in 2010 to 78% in 2025, so it can become a fundamental pillar for further economic development. It will also place new demands on the region’s policy makers for efficient, high-quality public services. To meet these demands countries will need to expand their fiscal space by introducing reforms to increase fiscal revenue and by setting up institutions to ensure that government resources are spent on projects that greatly benefit society. Meanwhile, the deficiencies in the region’s infrastructure and logistics considerably hinder economic growth, and will therefore require additional financial effort by the public sector and substantially better quality spending. In addition to the new demands for public services from Latin America’s “middle classes”, public policies must provide growth in a way that also improves the market distribution of income in the long run. Therefore, the economic structure must create opportunities for more and better jobs and greater productivity for large sectors of society to consolidate the emerging “middle class”. These needs are even more pressing in the light of Latin American integration into the context of shifting global wealth, led by the Asian economies.

The current economic climate is characterised by a shift in global wealth towards emerging economies This transition is mainly a result of China’s and India’s economic modernisation and their integration into the world economy. The size of these economies, in conjunction with their rapid, sustained growth and their strong demand for natural resources, has supported growth in many emerging and developing economies. While at the turn of the century non-OECD economies accounted for 40% of the global economy, by 2010 this figure had risen to 49%, and by 2030 it is projected to rise to 57%. This is in sharp contrast to the contribution made by Latin America and the Caribbean, which remains at the 1990s level of between 8% and 9%.

The emerging economies, including those in Latin America, must avoid falling into the middle-income trap, and this would help them satisfy the needs of their “middle classes”.

A rise in per capita income in emerging economies is bolstered by factors that characterise early-stage economic development, such as urbanisation, demographic shifts, cutting the size of the agricultural workforce, and closing the technology gap. Because these sources of development reach their limits, economies often see their per capita income stall, a phenomenon known as the middle-income trap. The middle-income trap is a source of vulnerability for the emerging “middle classes”, 6 which demand more and better public services, and it can reduce social mobility and create a more convulsive social environment.

The increasingly dynamic role of the Asian emerging economies in global shifting wealth is a challenge for the competitiveness of many of the region’s manufacturing industries.

China’s development pattern combines elements such as factor endowments, scale and productivity that considerably bolster the competitiveness of Chinese manufacturing. Latin America, for its part, is faced with systematic problems that make it difficult for the region to raise its productivity due to the limitations of its development model, from structural heterogeneity to low rates of savings. Growing competition from Asia’s emerging economies magnified the impact of these limitations, counteracting some of the natural advantages that some Latin American countries enjoy, such as being located close to the United States. This trend towards de-industrialisation in Latin America caused by endogenous and exogenous factors can be counteracted by the development of new capacities to produce increasingly sophisticated goods. i

Source: LATIN AMERICAN ECONOMIC OUTLOOK 2014 Logistics and Competitiveness for Development © OECD/UN-ECLAC/CAF 2013

You may have an interest in also reading…

Loita Capital Partners: A Reach as Wide as the African Continent Itself, and Still Roaring with Ambition

Pan-African by nature and global in its sense of drive, Loita Capital Partners has garnered a reputation for its pioneering

African Governments Invest in Skills in Sciences, Engineering, and Technology

President Macky Sall of Senegal launches a new Regional Scholarship and Innovative Fund in Johannesburg, South Africa, in June 2015.

Saudi Arabia’s Capital Market: Foreign Investors Told “Not Just Yet”

The regulator of the Saudi Arabia stock market – by far the largest of the Gulf Region – isn’t making