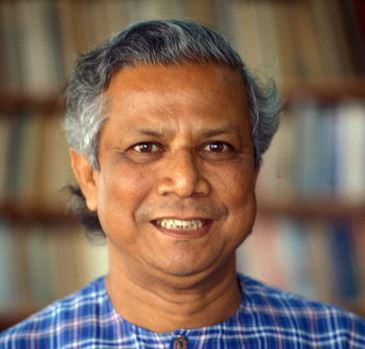

Muhammad Yunus: Enabling the Poor to Rise and Prosper

Muhammad Yunus is a soft-spoken gentleman with a South Asian accent. When he speaks, presidents strain to listen. Being one of only seven people to have won the Nobel Peace Prize, Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Congressional Gold Medal, Mr Yunus does not need the praise of CFI.co to boost his profile. However, we are going to give praise anyway.

Muhammad Yunus is a soft-spoken gentleman with a South Asian accent. When he speaks, presidents strain to listen. Being one of only seven people to have won the Nobel Peace Prize, Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Congressional Gold Medal, Mr Yunus does not need the praise of CFI.co to boost his profile. However, we are going to give praise anyway.

Muhammad Yunus is the founder of Grameen Bank, a Bangladesh-based bank and a pioneer in the world of microfinance. In the mid-seventies, while visiting the poor villages around his native Chittagong, a port city in Bangladesh where he was head of the economics department at the local university, Mr Yunus took an interest in the business practices of villagers. He observed that very small loans could have a disproportionate effect on their lives.

Traditional banks were unwilling to give out loans, however small, to the poor because of the high risk of default, leaving many at the mercy of loan sharks. Mr Yunus believed a viable business model could be made for offering loans to these poor and so he set out to test his theory. He gave 42 women small loans amounting to a grand total of 27 US dollars. All the women made a small profit on their loans.

In 1983, after finally securing a loan from a government bank, Mr Yunus established the Grameen Bank, which today offers financial services to very poorest in Bangladesh. Through the Grameen Foundation he has now set up similar projects across the world.

Grameen Bank works on a few basic principles. Firstly, most of their borrowers are female; this is partly an exercise in women empowerment and partly because it is believed that women make for more dependable clients. Secondly, Grameen Bank adheres to a system of solidarity lending. In every village the bank operates, local agents offer separate loans to individuals. Together, these are managed as a group in which members are collectively responsible for each other’s payments. The theory holds that this practice eliminates the need for collateral, gives lenders a support group, and cuts down on administrative and management costs.

Mr Yunus has been heralded as a pioneer in the world of microfinance, and his work has gained tremendous recognition from governments and private sector institutions alike. He sees microfinance as the most effective method yet in poverty reduction. The idea is that these loans, as small as they may initially be, will give these poor unskilled entrepreneurs a foot on the economic ladder. The expectation is that the seed so planted will snowball them out of poverty and drive their children into school.

Today, Mr Yunus travels the world spreading his vision through talks and feature-length documentaries. However, Mr Yunus does have his share of detractors, and has had them every step of his journey.

From fundamentalist Muslim preachers warning villagers against accepting loans which they perceive as un-Islamic, to Marxists rejecting his practices as an affirmation of neoliberalism. There have even been accusations of embezzlement, but these were later found to be without merit. More serious and harder to ignore are the accounts of loan shark practises on the part of Grameen’s local agents resulting in lenders ending up in debt traps. Some cases of suicide have even been reported, though it is unclear to what extend this is down to Grameen Bank policy.

Perhaps even more damming to the core idea of microfinance are a number of studies reporting microfinance as largely ineffective in both poverty reduction and the empowerment of women.

The idea of the unskilled, illiterate poor of the world simply working their way out of poverty via a tiny loan that enables entrepreneurial endeavours doesn’t really stand up to reason. Exactly how many unskilled low-level entrepreneurs can an already dirt poor village sustain? Solidarity lending may even exacerbate the problem: Far from being a support network, most of these women – being of a similar skill level and all starting from the same place – are essentially competitors.

As such they depend on each other’s payments for obtaining subsequent loans. This results in peer-pressure and harassment for struggling members trying to keep up with payments. The sad truth is that in all likelihood most of these women would trade their loan for a job in a sweatshop in a heartbeat.

It would appear that microfinance is not the panacea against poverty that Mr Yunus and many others consider it to be. But that doesn’t in anyway lessen his accomplishment. Financial services are a great benefit to society, and Mr Yunus has found a viable business model to supply such services to the bottom 2.6 billion of this world.

To the odd entrepreneurial soul featuring in one of Mr Yunus’ many success stories, this is a tremendous benefit. By their success they may in turn benefit the larger community. Spread over a population of 2.6 billion, those benefits add up.

Microfinance may not singlehandedly elevate the world’s poor, nor should we expect it to, but neither is it the enemy of good. Through Grameen Bank and other programs such as Grameen Telecommunications, Mr Yunus has placed powerful tools and information in the hands of the poor of Bangladesh. Through his many global initiatives, Mr Yunus is now spreading his ideas to the rest of humanity: A man trying to make a difference and succeeding marvellously well at it.

You may have an interest in also reading…

Our Hero Justina Mutale: Postive Runway

Founder and CEO of the NGO Positive Runway, Justina Mutale was admitted to the UK’s Black 100+ Hall of Fame

Ida, Data and Women’s Health: It’s Win-Win with the Clue App

From investment opportunities to the pursuit and provision of venture capital, the purse strings of financial dealings are very often

Pioneering Shari’ah Finance Philosophy with a Go-Ahead, Client-Centric Stance

Collaboration and consideration of diversity has taken MIB to the forefront of banking in Maldives The story of the Maldives