OECD: Achieving a Resilient Economic Recovery

Author: Rintaro Tamaki, Deputy Secretary-General and Acting Chief Economist of the OECD

The recovery from the Great Recession has been slow and arduous, and has at times threatened to derail altogether. However, the major advanced economies are finally gaining traction and momentum. Private-sector confidence is rebuilding. After years of weakness, investment and trade volumes have started to rebound. While unemployment remains unacceptably high, the labour market situation is improving in most countries and has stopped deteriorating virtually throughout the advanced economies.

On the other hand, the pace of growth in the major emerging market economies has slowed. Part of this deceleration is benign, reflecting cyclical slowdowns from overheated starting positions – the growth rates now seen in China are undoubtedly more sustainable from both economic and environmental perspectives than the double-digit pace of a few years ago. However, managing the credit slowdown and the risks that built up during the period of easy global monetary conditions could be a major challenge.

The likelihood of some of the most worrisome events that have preoccupied markets and policymakers in recent years coming to pass has diminished. Risks are overall better balanced although still tilted to the downside. Financial tensions in emerging markets are one risk that could blow the global recovery off course and have bigger spill-overs than anticipated. It is not the only one: Falling inflation in the euro area could turn into deflation. Geopolitical risks have also increased since the start of the year.

“The high levels of government debt in all major advanced economies mean that there is little room for fiscal accommodation.”

Policy focus can now switch from avoiding disaster to fostering a stronger and more resilient recovery. The legacy of the crisis still needs to be addressed. The crisis has left scars in the labour market, notably higher unemployment and lower participation of the more vulnerable groups. Growth prospects are weaker than they were in the pre-crisis era. Moreover, one of the key lessons of the crisis is the need to make our economies and societies more resilient – more able to withstand shocks, and more inclusive with the welfare gains from stronger growth better shared across the population. While steps have been taken in both areas, much more needs to be done.

After difficult years of low growth and fiscal stringency, policymakers are facing these challenges with depleted political capital. But they need to seize the opportunity to set global growth on a stronger and more sustainable footing. This key to supporting confidence and has to be backed by macroeconomic and structural policy actions, including the promotion of institutional frameworks that support the implementation of reforms.

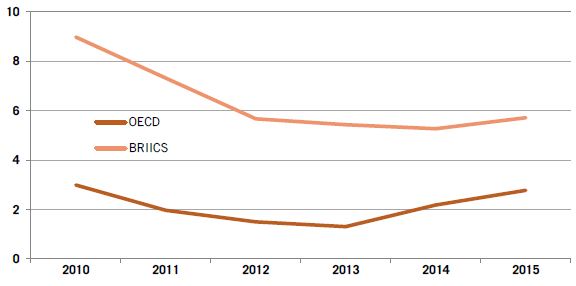

Real GDP Growth (per cent). Source: OECD May 2014 Economic Outlook database.

Given persisting downside risks, high unemployment, below-target inflation, and high levels of government debt, monetary policies need to remain accommodative in the main OECD areas. In particular, we call on the European Central Bank (ECB) to take new policy actions to move inflation more decisively towards target and to be ready for additional non-conventional stimulus if inflation were to show no clear sign of returning there.

The high levels of government debt in all major advanced economies mean that there is little room for fiscal accommodation. Nevertheless, following significant progress in stabilising their public finances, most OECD countries can afford the planned slowdown in structural budget improvement. This is not the case in Japan where consolidation needs remain very large. Given its high level of public debt, a credible medium-term fiscal consolidation plan is essential.

In most countries, reducing public debt to more prudent levels and managing future pension and health liabilities will pose a challenge and requires fiscal reforms to ensure the sustainability of public finances without compromising the quality of public services.

It is now time to speed up the pace of structural reforms. Such reforms, while often facing resistance from vested interests, can offer a win-win by raising growth potential and allowing many of the poorest to achieve higher living standards. These policies are critical to the success of Abenomics in Japan, as well as to rebalance of the euro area and foster the convergence to higher incomes by emerging economies.

While impressive reform efforts have been made by crisis-hit countries, there remains substantial scope to boost productivity and create jobs through policies aimed at removing barriers to domestic and international competition in both advanced and emerging economies. This would increase innovation and help get the most out of global value chains, as well as boost investment in the near term and support resilience.

As unemployment starts receding, measures to tackle long-term unemployment, and make sure it does not become entrenched, are a high priority that requires reforms to remove obstacles to more robust job creation and strengthen and redesign active labour market policies.

About the Author

Mr. Rintaro Tamaki was appointed Deputy Secretary-General of the OECD on August 1, 2011. His portfolio includes the strategic direction of OECD policy on Environment, Development, Green Growth, Financial Affairs and Taxes.

Mr. Tamaki is also currently acting Chief Economist and assumes the responsibility as the OECD Representative at the Deputies’ Meetings of the G20.

Prior to joining the OECD Mr. Tamaki, a Japanese national, was Vice-Minister of Finance for International Affairs at the Ministry of Finance, Government of Japan.

During his prominent 35-year career at the Japanese Ministry of Finance, Mr. Tamaki has worked on various budget, taxation, international finance and development issues. He worked as part of the OECD Secretariat from 1978 – 1980 in the Economic Prospects Division and from 1983 – 1986 in the Fiscal Affairs Division of the Directorate for Financial, Fiscal and Enterprise Affairs (DAFFE). In 1994 Mr. Tamaki was posted to the World Bank as Alternate Executive Director for Japan and in 2002 as Finance Minister at the Embassy of Japan in Washington DC. He then became Deputy Director-General (2005), before becoming Director-General (2007) and subsequently Vice-Minister for International Affairs (2009) at the Ministry of Finance.

Mr. Tamaki graduated in 1976, L.L.B. from the University of Tokyo and has held academic positions at the University of Tokyo and Kobe University. He has published books and articles on international institutions, the international monetary system, development, debt and taxation.

You may have an interest in also reading…

Lessons from China

For the first time in nearly half a century China’s economy has stopped growing. The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS)

Vector Casa de Bolsa: Five Decades Driving the Growth of the Mexican Economy

As Vector Casa de Bolsa approaches its 50th anniversary, it is time to reflect on the company’s remarkable journey and enduring impact

A Handbag’s World: How Hermès Handbags Became Blue-Chip Assets

A new kind of currency has emerged in high finance—soft to the touch, exquisitely crafted and wrapped in mystique. The