Harvard Business School on Impact-Weighted Accounts: the Missing Piece in Economy Puzzle

Harvard Business School: the north facade of the Baker Library

Capitalism is in need of a renaissance. Despite headlines of strong global economic growth, there are signs that all is not well.

Environmental advocates have been leading calls for change before the climate crisis produces irreversible changes to our world. Now, investors, politicians and business leaders are heeding that call, as evidenced by the recent declarations by the World Economic Forum and the Business Roundtable. At Harvard Business School, impact-weighted accounts are seen as the missing piece needed to catalyse change.

Across the world, particularly in capitalist economies, the vast majority of businesses seek continual growth. Most businesses in a competitive market are not considered viable without long-term growth in revenues and/or profits (commonly referred to as performance).

Huge consultancies have emerged to help companies optimise operations, customer-segmentation, and churn-reduction to support revenue and growth. Business schools have designed curricula to provide students with the requisite skills.

In the current accounting-reporting frameworks, and much of corporate law, there are two groups of stakeholders whose rights are held above all others: equity and debt owners. In the course of normal business, debt holders are expected to be paid the contractually defined interest and principle amounts, otherwise they can bankrupt the company, and equity owners are entitled to any profits after earnings.

The maximisation of performance, beyond the amount needed to pay debt service, is for the benefit of equity owners. Employees, societies, and the environment have largely been considered to be the means to generate the payments to the primary stakeholders, rather than stakeholders in their own right.

Laws protecting employees, such as the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) in the US, protect against the potential effects of an unbounded performance-focused system — which prioritises corporate owners.

Capitalism and globalisation have, by many measures, been successful. Substantial progress has been made in almost every measure of human wellbeing. But these gains are not without challenges, and the scale of those challenges is becoming unmanageable. The systems which brought growth are also the cause of negative environmental, employment and product impacts.

The planet and its climate are at a tipping point. Employment trends are creating welfare dispersions. Even in the wealthier, developed economies, there are massive disparities that have consequences for health, happiness, and security. The legitimacy of business, and the promise of capitalism, are increasingly called into question.

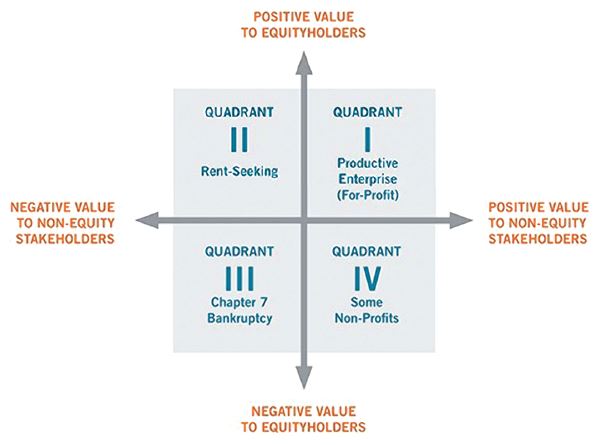

The legitimacy of a business depends on its ability to create value for society. Companies that create value for investors, workers, customers, suppliers and the larger ecosystem are evidence of businesses’ power to increase wellbeing. Directors and executives who manage companies aim to combine resources (raw materials and labour) in strategic ways that create more value than they consume, represented by quadrants I and II.

Once they have developed a business model that creates significant value, a company’s managers decide how to allocate this among stakeholders. In capital markets, businesses deemed successful by owner-centric measures may destroy value for other stakeholders, represented by quadrant II. Traditional accounting methods that use a single metric to measure firms ignore this.

Businesses seeking to maintain a licence to operate may protect against this non-financial stakeholder value-destruction by measuring the total value delivered. In the same way that accounting standards define which financial transactions to capture, and how to account for them within financial statements, we require a methodology that reveals a firm’s overall value to society. Without such a transformation in business accounting, strategic analysis will continue to ignore negative and positive impacts on non-financial stakeholders.

Impact-weighted accounts are monetary line items on a financial statement — income statement or a balance sheet — to supplement the financial health statement. The aspiration is an integrated view of performance which allows investors and managers to make informed decisions based on private gains and losses, as well as the impact a company has on society and the environment.

Impact-weighted accounts change our intuition. To build an impact economy, all participants must understand that actions have consequences. In the absence of such accounts, we are creating the illusion that most commercial activities have no impact. Investors incorporate existing ESG metrics into their investment decisions today, investing based on inputs or outputs, not impact. This forces the assumption that similar inputs produce equal impacts across funds.

Impact-weighted accounts would allow for a better understanding of the societal and environmental effects of ESG investing. They would provide a scalable, replicable means to compare ESG Funds, reducing diligence and search costs. Allowing informed decisions gives corporate managers new information about costs and benefits.

Currently, impact information is conveyed in the language of the respective disciplines, such as GHGs and Quality Adjusted Life Years. This is challenging for managers unfamiliar with these terms to evaluate the economic benefits of their choices. By converting impact into monetary terms, the full scope of value creation or destruction becomes apparent.

Strengthening Incentives

With impact-weighted accounts, data can be used to create incentives toward the SDGs.

It is appropriate to draw a parallel with the development of modern financial infrastructure. Asset and portfolio risk measurement and quantification, which revolutionised asset allocation and portfolio management, are built on the uniform financial disclosures frameworks.

Monetisation of social and environmental impacts represents the next step in portfolio theory, and will permit the development of effective risk-return-impact optimisation tools and the identification of a new efficient investment frontier.

The potential to systematically model and optimise impact by in similar metrics to those used for risk and returns, versus current market practice of disregarding impact completely or by conducting separate overlay qualitative and quantitative assessments, has the potential to dramatically change capital flows throughout our system.

To catalyse the uptake of impact-weighted accounts, numerous efforts are underway in addition to our research efforts at Harvard Business School. The OECD, SASB and Social Value International are jointly leading a working group to explore how current standards form a larger system for impact measurement and management, the working group for this effort – convened by the IMP – includes, but is not limited to, many members of the auditing and accounting firms. The Value Balancing Alliance, True Price, The Impact Institute, the Capitals Coalition, & ISO, among others, are also working toward building stakeholder support, conducting research, and piloting projects with companies to build the ecosystem around greater impact reporting and monetisation. We believe that even without near-term uptake of impact-weighted accounts by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in the United States and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), impact-weighted accounts will be adopted by the market through the use of parallel accounting statements. Work with the accounting and audit community to build rigor around the process of gathering data and reporting on and eventual monetisation of impact will be critical to achieving an audit standard for these parallel accounting statements.

Work with the accounting and auditing communities to build rigor around the process of gathering data and reporting on and eventual impact monetisation will be critical to achieving an audit standard for these parallel statements.

About the Author

Author: Robert Zochowski

Robert Zochowski is the Director and Senior Researcher for The Impact-Weighted Accounts Project and the Social Impact Collaboratory at Harvard Business School. Previously, Rob was a Vice President at Goldman Sachs where he had roles in Investment Product Innovation, Strategy & Development, Alternative Investment Strategies, and Private Wealth Management. Rob has consulted with the National MS Society and the World Wildlife Fund and was a 2019 Three Cairns Climate Fellow focused on mitigating the environmental effects of charcoal use in Mozambique. Rob received his MBA from Columbia Business School in the Executive Program where he concentrated on Social Enterprise and Impact Investing, graduating Deans Honors with Distinction (top 10%). He was featured in Poets and Quants annual 100 Best & Brightest Executive MBAs list. Rob is the 2019 recipient of the Carson Family Changemaker Award which recognizes commitment to the field of social enterprise. Rob earned his Bachelor’s Degree in Economics from Georgetown University where he graduated Magna Cum Laude.

You may have an interest in also reading…

Innovating Healthcare: The Journey of GKSD Investment Holding Under a Watchful Eye

Group president Kamel Ghribi’s passion for excellence and industriousness has transformed the sector. Kamel Ghribi, president of GKSD Investment Holding

BlueRock’s Ronny Pifko: A Solid Strategy Built on Strong Foundations

CFI.co’s Jason Agnew finds out from BlueRock Group’s Managing Partner, Ronny Pifko, how they’ve kept constructive during testing times. When

Loita Capital Partners: A Reach as Wide as the African Continent Itself, and Still Roaring with Ambition

Pan-African by nature and global in its sense of drive, Loita Capital Partners has garnered a reputation for its pioneering