Dollar Dominance: Greenback Will Endure Current Hardships

Financial sanctions on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine sparked speculation that the weaponisation of access to reserves in dollars, euros, pounds, and yen would spark a division in the international monetary order.

Financial sanctions on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine sparked speculation that the weaponisation of access to reserves in dollars, euros, pounds, and yen would spark a division in the international monetary order.

China would strengthen its international payments system and accelerate the establishment of the Renminbi as a rival reserve currency to reduce its vulnerability. Countries facing geopolitical risks in their relationship with the US and Europe would seize the opportunity to switch out of the dollar system. But there’s a way to go between intention and action.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently released a study on the evolution of international reserves since the beginning of the century. “Dollar dominance” — the US’s share of foreign trade invoicing and international debt issuance and non-banking transactions — is above what the country’s share of international trade, international bond issuance, and cross-border borrowing would suggest.

This remains, despite the falling share of US GDP in the global economy. From the 1970s onwards, it survived the end of gold convertibility and the fixed exchange-rate regime inherited from Bretton Woods. Its presence in banking and non-banking transactions actually grew after the 2007-08 global financial crisis.

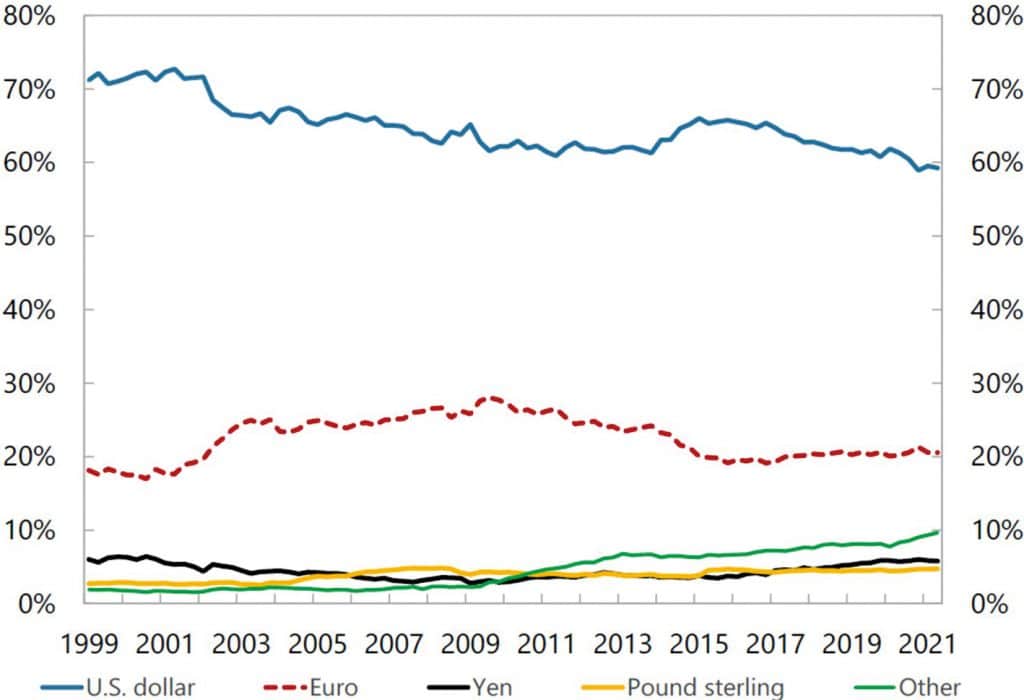

Figure 1: Currency Composition of Global Foreign Exchange Reserves 1999–2021.

The IMF report shows a reduction in the degree of that dominance, with the dollar’s share of central bank reserves falling, down 12 percentage points from 71 percent in 1999 to 59 percent last year. That was not in favour of sterling, the yen or the euro, despite the rise that the euro experienced during its first decade of existence (Figure 1). Instead, it favoured what the IMF calls “non-traditional reserve currencies” — the Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, Swiss franc, and Renminbi — which reached 2.6 percent of the total.

Four gravitational factors favour the continuation of the dollar’s central position in international financial markets, in trade invoices and payments, and in public and private foreign exchange reserves. The relative expansion of the other currencies depends on how successfully they manage to offset those factors.

First, the more extensive installed base for dollar-denominated transactions favours the greenback. The increase in liquidity and the reduction in transaction costs in the non-traditional foreign exchange markets — including technological improvements in platforms — helped reduce this.

No other monetary system offers an equivalent volume of investment-grade government bonds as that of the US. That volume allows central banks to accumulate reserves, and private investors to use them as a haven — something reinforced by quantitative easing since the global financial crisis. The 2012 announcement by the-then president of the European Central Bank, Mário Draghi — that he would do “whatever it takes” as a last-resort provider of liquidity for euro-denominated assets issued in the eurozone — was important. The European Recovery Fund was created last year. The global supply of liquid and safe-haven assets usable as central bank reserves tended to widen, in favour of the euro.

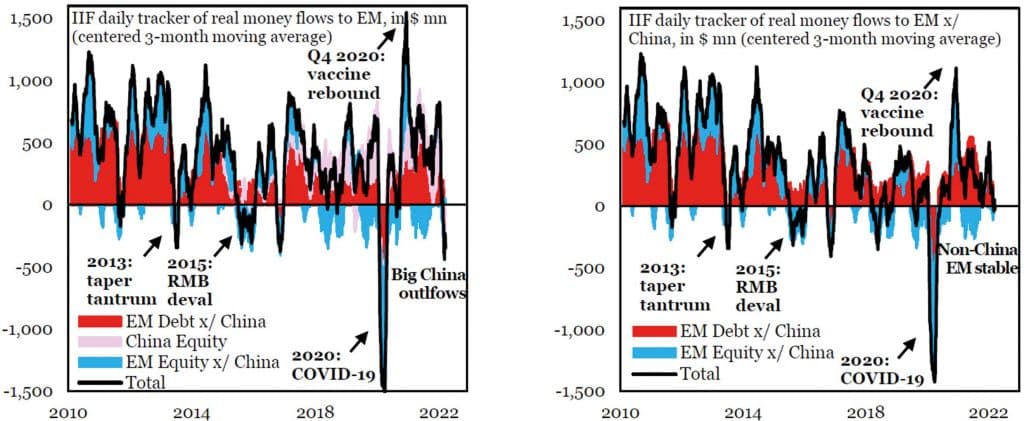

Figure 2: China sees large outflows, while the rest of EM is holding up.

It is also worth noting that non-traditional currencies were favoured by a partial search for returns in reserve management. Central bank balance sheets have taken on enormous proportions in recent times. Now, some of them separate what would be the appropriate tranche for liquidity management (the reason for reserves in liquid and low-risk assets, for stabilisation), from another investment tranche, possibly allocated in less liquid but more profitable assets. The search for diversification helped non-traditional reserves.

Another thing in favour of the dollar would be the absence of regulations restricting liquidity and asset availability, including capital controls. Despite the sanctions on Iran, Venezuela, and Russia, there is a difficulty for Chinese bonds compared to those in dollars and the other three major currencies.

Since the global financial crisis, China has sought to extend the use of the Renminbi in international trade, and as a reserve asset at other central banks. This was followed by a proliferation of foreign exchange swap lines with other countries.

But while trade transactions and reserves by central banks and other global public investors may reinforce the Renminbi’s position as an alternative currency to the dollar, euro, yen, and pound sterling, the qualitative leap toward its internationalisation as a reserve currency will only happen when confidence in its convertibility is sufficient to convince private investors. It is not by chance that the currency swap lines with China have been little used, while those of the countries with the Federal Reserve have been activated to stabilise flows.

The reserve issuer must accept that large amounts of its currency circulate the world, and that foreign investors help to determine domestic long-term interest and exchange rates. Chinese financial authorities do not appear to be considering relinquishing control. They will probably seek to expand the use of the Renminbi as much as possible while retaining control, and without building some parallel regime to the existing one.

Recent portfolio foreign capital movements into China show what is at stake, and the potential cost to China. Data released by the Institute of International Finance (IIF) revealed an unprecedented outflow of portfolio (debt and equities) capital from China in the wake of the Russian invasion. Such flows remained stable in other emerging economies (Figure 2). The timing suggests links with the war in Ukraine and sanctions. It is not opportune for China to issue any signs of a sudden departure from the system where it currently operates, nor of a possible collaboration with Russia to help it circumvent sanctions.

The relative dominance of the dollar appears to be declining — but at a very gradual pace.

You may have an interest in also reading…

Otaviano Canuto, World Bank Group: Navigating Brazil’s Path to Growth

Brazil’s macroeconomic management faces four major immediate challenges. The response to them will be strengthened if economic agents could have

The Great Rebalancing: Capital Allocation in an Age of Fragmentation and Convergence

After a long stretch in which US markets served as the default setting for global portfolios, 2026 is beginning to

Global Wage Report

Global wages remain far below pre-crisis levels, says a new United Nations report, which points to a continuing slowdown in