IMF | Gulf Cooperation Council: Economic Prospects and Policy Challenges for the GCC Countries

Executive Summary

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

The already sluggish global recovery has suffered new setbacks and uncertainty weighs heavily on prospects. The euro area crisis intensified in the first half of 2012 and growth has slowed across the globe, reflecting financial market tensions, extensive fiscal tightening in many countries, and high uncertainty about medium-term prospects. Activity is forecast to remain tepid and bumpy, with a further escalation of the euro-area crisis or a failure to avoid the “fiscal cliff” in the United States entailing significant downside risk.

In the MENA region, many countries are going through difficult transitions. Changes of government in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen were accompanied by varying degrees of social unrest and associated disruptions to economic activity, and the conflict in Syria has continued to intensify. Social instability and political uncertainties—although in several cases having receded in recent months—remain substantial, and the near-term growth outlook for the countries in transition is generally subdued. The medium-term reform agenda necessary to lay the basis for inclusive private sector led growth has yet to be tackled. The IMF is engaging closely with these countries—including through financing programs in Yemen, Jordan and Morocco—but additional financing needs remain large. Stronger cooperation with GCC countries who are major financiers for these countries could be of great benefit.

The GCC economies are enjoying high growth. The combination of historically high oil prices, expanded oil production, expansionary fiscal policies, and low interest rates is supporting buoyant economic activity. Fiscal and external surpluses are large, inflation is moderate, and prospects for growth remain positive. At the same time, however, the economies remain dependent on hydrocarbon extraction and rising government spending has raised breakeven oil prices, implying heightened vulnerabilities.

Risks to the GCC stemming from exposure to Europe are limited, but the impact via oil demand and prices could be substantial. A rapid deterioration in the global economy could bring about developments similar to what the region experienced in 2009, including a sharp fall in oil prices and disruptions to capital flows. Although most GCC countries have sufficient savings to cushion even a sizeable shock, a prolonged drop in oil prices could test available buffers. The strong baseline outlook for the GCC economies implies diminishing need for near-term policy stimulus. Most GCC countries can plan to reduce the growth rate in government spending in the period ahead, which would help prevent any prospect of overheating and also improve longterm fiscal positions. With low inflation, the accommodative monetary stance as implied by the region’s currency pegs remains appropriate.

Given the uncertain global outlook, however, continued emphasis on reducing vulnerabilities will be important alongside greater focus on strengthening the foundations for longer-term growth and diversification. This includes: (i) reducing fiscal risks and improving the fiscal outlook by containing increases in spending on entitlements that are hard to reverse and instead prioritizing growth-enhancing investments in infrastructure; (ii) strengthening fiscal frameworks and institutions; (iii) bolstering the financial sector, including through continuing to enhance supervision and macropudential policy frameworks and by deepening domestic debt markets; and (iv) advancing private sector job creation for nationals.

International Context

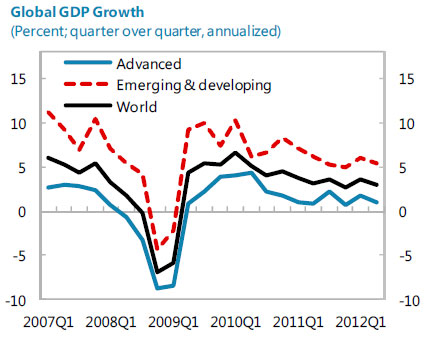

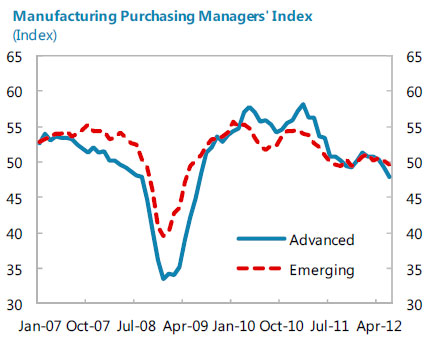

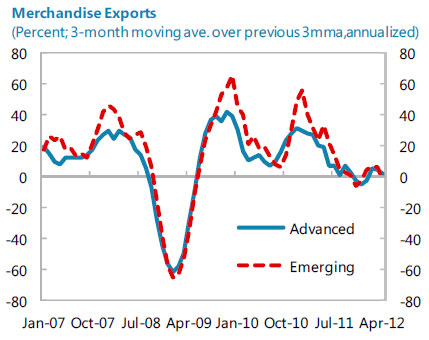

Economic activity showed widespread weakness over the past year. The downturn has been most pronounced in the euro area periphery where most countries are now in recession. The slowdown has been observed in all regions, however, reflecting financial market tensions, extensive fiscal tightening in many countries, and cross-country spillovers. As demand for durables flagged, global manufacturing was particularly hard hit and global trade stagnated.

Sources: DataStream; Haver; and IMF staff estimates.

The euro area crisis deepened in the first half of the year but financial tensions have recently moderated. The euro area periphery has been at the center of several bouts of intense financial market stress, triggered by political and financial uncertainty in Greece, banking sector problems in Spain, and doubts about governments’ ability to deliver on fiscal adjustment and the extent of partner countries’ willingness to help. As the crisis intensified, periphery bond yields rose, stocks fell—in particular those of banks and peripheral economies—and the euro depreciated. This culminated in Spanish spreads reaching a euroera

record in late July. Since then, a new bond-buying program announced by the European Central Bank and further monetary easing by U.S. Federal Reserve have led to a marked improvement in market sentiment.

Sources: DataStream; Haver; and IMF staff estimates.

Growth in advanced economies has slowed noticeably. In Europe, as the downturn in the euro area periphery deepened, growth also slowed considerably in the core, and real GDP contracted in the United Kingdom. In the United States, employment and output growth was lower than expected even as the housing market is showing tentative signs of improvement. In Japan, growth fell sharply as the boost from reconstruction activity following last year’s earthquake and tsunami started to wane.

Sources: DataStream; Haver; and IMF staff estimates.

Emerging markets—especially those in Asia—continue to outperform advanced economies but they too have seen the momentum fade. Although still strong at an annual rate of almost 8 percent in the second quarter, the pace of real GDP growth in China has continued to decline following earlier policy tightening aimed at reducing price pressures and as a result of weak external demand. A partial reversal of this earlier policy tightening has yet to gain traction, and slowing growth in China has affected activity throughout the region. The pace of expansion in India’s economy has also moderated significantly, with weaker business sentiment weighing in. Along with slower growth, many emerging markets have been hit by investor risk aversion, which have led to equity price declines and in some cases capital outflows and currency depreciation.

Developments in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region

Overall real economic growth for MENA fell from 5 percent in 2010 to 3.3 percent in 2011 and is projected to pick up to 5.3 percent in 2012. Much of this movement in region-wide growth has, however, been driven by the 2011 collapse and 2012 rebound of Libya’s oil production.

Several MENA economies have been severely affected by ongoing political transitions and associated disruptions to economic activity. Changes of governments in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and Yemen were accompanied by varying degrees of social unrest, and the political transition continues. Moreover, the conflict in Syria continues to intensify and is affecting its neighbors. The countries in transition have all seen interruptions to production, and unrest also led to wider declines in tourism and foreign direct investment, which have not been able to rebound strongly due to weak conditions in Europe and elsewhere in the world. Management of popular expectations will remain a challenge.

Developments in GCC Countries

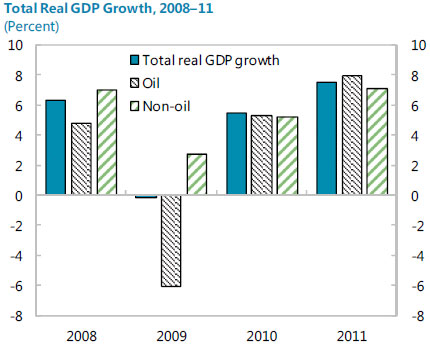

The GCC economies are growing at a strong pace. Output growth has in most countries been steadily increasing since hitting a low in 2009 in the wake of the global financial crisis (Figure 4). In 2011, overall real GDP growth for the GCC reached 7.5 percent—the highest since 2003. This occurred as oil production rose by over 10 percent and as non-hydrocarbon growth increased in all countries, except Bahrain where social unrest has taken a toll.

Fiscal policies have provided significant stimulus. In 2011, as governments responded to social pressures and took advantage of surging oil revenues, overall spending grew by some 20 percent in U.S. dollar terms, about double the pace of the previous two years. Much of the higher spending was in current expenditure, including from larger wage bills (all countries) and introduction of new benefits for job-seekers (Oman and Saudi Arabia). Capital expenditure also increased sharply in Saudi Arabia.

Sources: DataStream; Haver; and IMF staff estimates.

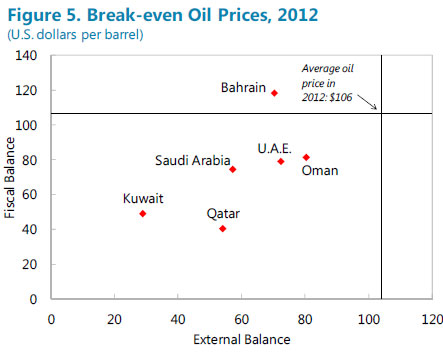

Fiscal and external surpluses remain large, but higher government spending has raised breakeven oil prices. Driven by the surge in oil revenue, the GCC’s fiscal surplus is estimated to have reached about 13 percent of GDP in 2011 and the external current account about 24 percent of GDP. Both these balances are projected to remain broadly stable in 2012 as oil prices have leveled off. Along with rising government spending, however, the underlying breakeven oil prices have continued to increase. Although mostly remaining well below actual oil prices, breakeven oil prices are at a historical high, implying heightened vulnerabilities.

Sources: DataStream; Haver; and IMF staff estimates.

Excerpts of report from Annual Meeting of Ministers of Finance and Central Bank Governors, October 5–6, 2012, Saudi Arabia.

Excerpts of report from Annual Meeting of Ministers of Finance and Central Bank Governors, October 5–6, 2012, Saudi Arabia.

Prepared by May Khamis, Tobias Rasmussen, and Niklas Westelius.*

* The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be reported as or attributed to the International Monetary Fund, its Executive Board, or the governments of any of its member countries.

You may have an interest in also reading…

CFI.co Meets the CEO of Excellencia Investment Management: Ammar Dabbour

Mr Ammar Dabbour started his career in finance in 2001 and has since gained a broad scope of responsibilities ranging

European Investment Bank: “Vienna Initiative” Keeps Credit Flowing

International financial institutions have joined forces to help calm economic turbulence and avert a collapse in the provision of credit

Home is Where the Mortgage is: 2008 Crisis has Lessons for Sector

Of all the sectors affected by the pandemic, the housing market has performed better than expected. In 2008, home loans